Optimism in Lebanon is often hard to sustain, as the country is mired in crises and plagued by countless missed opportunities. These missed opportunities are so frequent that they demonstrate, more starkly than anywhere else, that history has a way of recurring.

After more than two years, Lebanese lawmakers succeeded in electing the commander of the Lebanese Armed Forces General Joseph Aoun as President by an overwhelming majority. President Aoun’s inauguration speech on January 9 outlined a synopsis of his program. He reaffirmed his commitment to restoring the state’s monopoly on the use of arms and pursuing political, economic, social, and governance reforms. President Aoun also highlighted that Lebanon’s governance crisis stems from “a failure in the application of laws or a poor interpretation and formulation of these laws.”

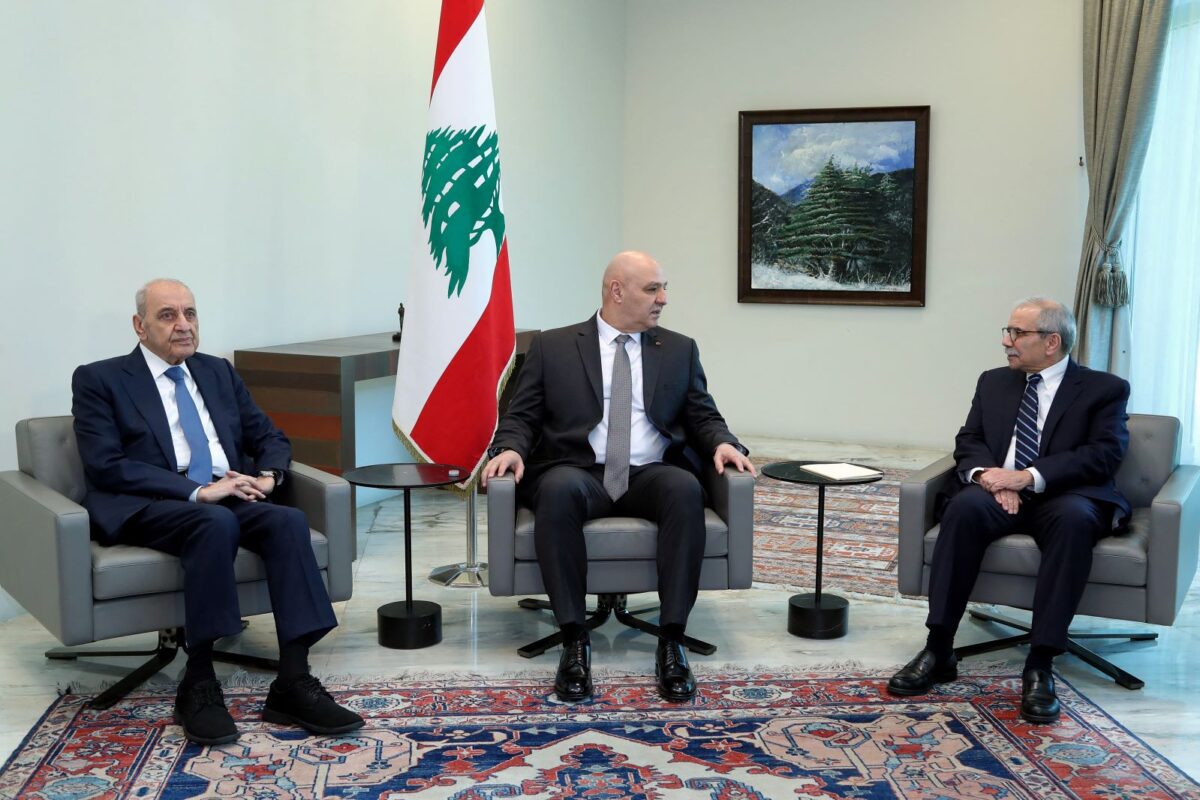

The optimism generated by President Aoun’s election gained further momentum just days later. On January 13, the President appointed Nawaf Salam as Prime Minister-Designate after Salam secured 84 out of 128 MPs’ votes in the binding consultations. The newly appointed PM was until his appointment the president of the International Court of Justice, a former Ambassador to the UN, and a renowned academic. By Monday evening, the outlook for Lebanon’s recovery appeared more promising than it had in decades, with a renewed sense of hope that the country could confront the challenges and distortions of its troubled past.

If luck mirrors fate, Lebanon’s fate seems to be one of persistent challenges. The governance crisis that President Aoun highlighted in his inauguration speech quickly came to the forefront. The Prime Minister-Designate failed to secure any of the 27 MPs’ votes, with these MPs also boycotting the non-binding consultations to form a government. This crisis is deeply rooted in the National Reconciliation Accord (Taif Agreement) of 1989, which was instrumental in ending the Lebanese Civil War.

The accord introduced constitutional amendments enacted in 1990, including a preamble to the Constitution consisting of 10 points. The final point asserts that “there shall be no constitutional legitimacy for any authority which contradicts the pact of mutual existence.” The interpretation of this article from the Constitution preamble will significantly impact the first government’s shape, role, and functions in President Aoun’s mandate. Also, this is not the first time Lebanon has witnessed a governance crisis that could be attributed to the Taif Accord.

One of the false narratives related to Lebanese domestic politics succeeded in creating ambiguity around the role of the Taif Agreement, claiming that it established a principle of winners and losers through the redistribution of powers among the three presidencies. Specific sectarian forces abused this narrative and constructed a sense of political grievance around it, aiming to ensure their continuity by using it as a weapon against other groups regardless of the latter’s name or influence.

The Taif Agreement established new constitutional institutions, including the Constitutional Council and the Senate. The Constitutional Council was entrusted with “interpreting the Constitution, monitoring the constitutionality of laws, and resolving disputes and appeals arising from presidential and parliamentary elections.” However, the purpose behind establishing the Constitutional Council was not fully adhered to. The constitutional amendment passed in September 1990 did not grant the Council the authority to interpret the Constitution as intended during the meetings in Taif, Saudi Arabia.

Today disputes over the interpretation of constitutional provisions have become a central tool in Lebanon’s political conflicts. Each political or sectarian faction now relies on its own constitutional experts to interpret the provisions of the Constitution as needed. This is particularly evident in analyzing the final article of the Constitutional preamble, which ties legitimacy to adherence to mutual coexistence. However, the mechanism for managing this relationship between legitimacy and mutual coexistence remains unclear.

Is it sufficient for all sects to be represented in government, ensuring parity between Christians and Muslims and proportional representation among sects, to deem a government legitimate? Or does legitimacy derive from the political parties representing these sects having the authority to appoint their ministers in the government?

Granting political groups represented in parliament the right to delegitimize an institution simply because they did not participate in naming some or all of its members contradicts the Taif Accord rather than adhering to it. The Taif Accord provided a governance roadmap for Lebanon based on a temporary phase to establish a balance between sectarian groups and between these groups and the state. It also outlined a permanent phase that fundamentally depends on the abolition of political sectarianism, wherein the relationship between citizens and the state is directly organized, free from the mediation of sectarian affiliations.

One of the few criticisms of the Taif Accord was the assumption that political, sectarian groups would willingly accept the abolition of political sectarianism. Still, the Taif Accord did not grant any sectarian group, even those monopolizing their sect’s parliamentary seats, a veto power or the ability to delegitimize institutions based on their lack of participation in appointing candidates.

What the Taif Accord did achieve, however, was to adjust the imbalance in the distribution of parliamentary, ministerial, and first-tier administrative positions between religions and sects.

To overcome this debate and manage the controversy, the Prime Minister-Designate might need to revisit the methodology for forming a government. The non-binding consultations conducted by the Prime Minister-Designate with MPs are not intended to solicit suggested candidates for ministerial positions. Instead, these consultations are meant to gather input regarding their expectations for the type and structure of the government, as well as the content of its ministerial statement. These consultations should not be an entry point for political parties to impose their candidates.

Therefore, instead of allowing political or sectarian groups represented in parliament to nominate candidates for ministerial positions, the Prime Minister-Designate should present a proposed cabinet directly to the President, in accordance with the Constitution, without discussing specific names with any political groups or MPs. It would then be up to the parliament as a whole to grant or withhold a vote of confidence for the new government.

There is always a need to revisit agreements or a constitution after a certain period. The Taif Accord, now 35 years old, is no exception. However, this agreement was never indeed given a fair chance. Between 1990 and 2005, it was implemented in a Syrian-influenced version, and since 2005, its application has been marred by competing veto powers bolstered by weapons outside the authority of the state.

Khalil Gebara is an academic and researcher.

The views in this story reflect those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of NOW.