The roaring years of Lebanon in the biographies of its 225 abandoned cinemas

His wife accuses him of living in the past and he takes it as a boast. Antoine Kabbabe told me about it himself, sitting at a table in a café in Badaro. Next to the steaming cups and his crossed and lived hands, La dernière séance, his last scene, the collected memory of an era in which Beirut shone and now does not exist – if not in memory. He wrote it, dedicating his book: “Je partage avec toi ce patrimoine qui n’existe plus que dans notre mémoire. Antoine.”

I emphasize it: our memory. No longer exclusive to the generation that built Lebanon, made it independent, embellished it with cafes and restaurants, theatres, cinemas, concert halls, luxury hotels, and then divided it into political pieces and religious bits – bits and pieces that soon ceased to have a reason, and caused, in fifteen years, the exodus of a million people, the death of 150,000, military occupation by two foreign powers, and the closure of 225 movie theatres.

For the generation of Antoine, the great caesura of Lebanese history is 1975, when everything changed. “There is a before and there is an after the civil war, in Lebanon.” Before: the 1950s and 1960s, the golden age, al-zaman al-jamil, as they say in Arabic.

“I am a lucky Lebanese because I lived through those years,” confesses Antoine, “and I can testify.” I would add: he is a lucky Lebanese because he is aware of the unrepeatable richness of this memory. School books interrupt the country’s history with the independence from the French mandate in 1943: but the history of cinemas, in school books – and that of cafés, restaurants, theatres, and luxury hotels closed forever by the war – this story of Lebanon would not have found space in school books anyway. It is the testimony of a life of before that belongs to ordinary people, to those who have gone through the Grande Histoire with the listless unawareness of those who survive the catastrophe concerning about everyday life; of great events not perceived if not with annoyance – the sadness for the closure of a cinema hall – or with the children’s enthusiasm of not having to go to school.

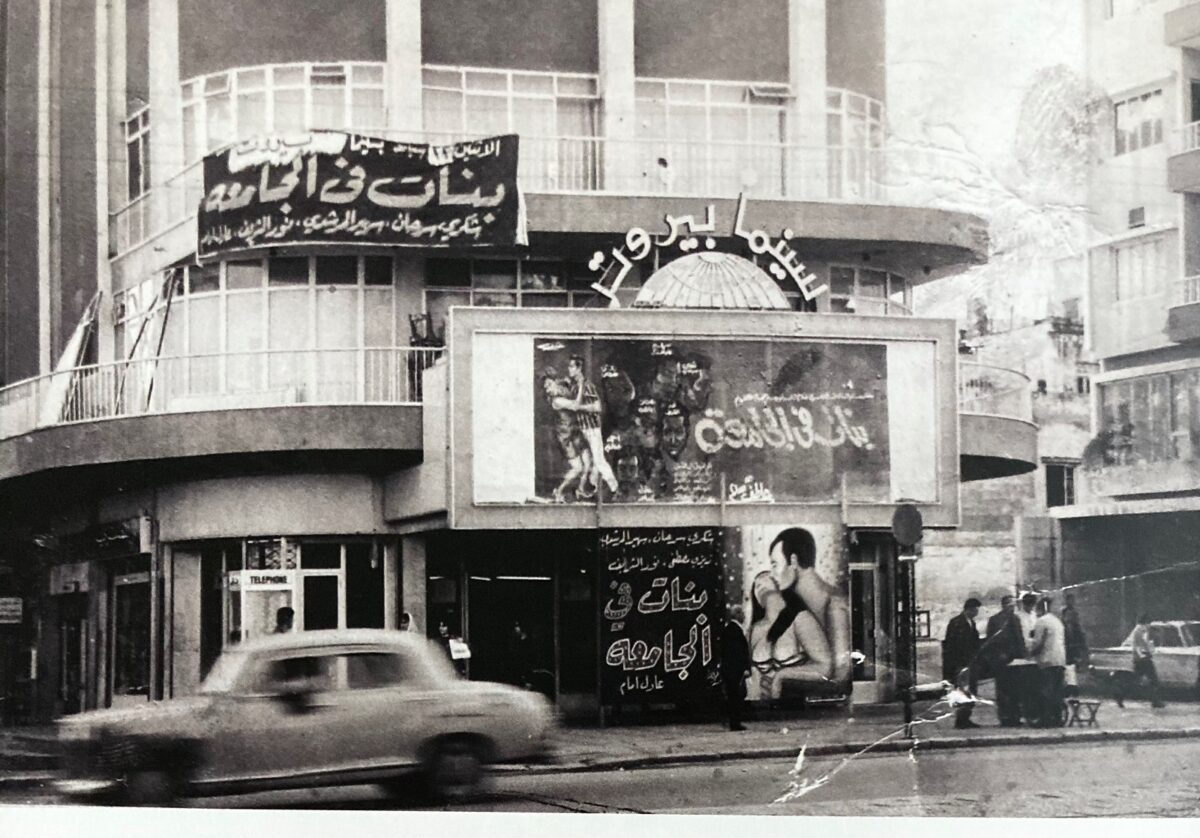

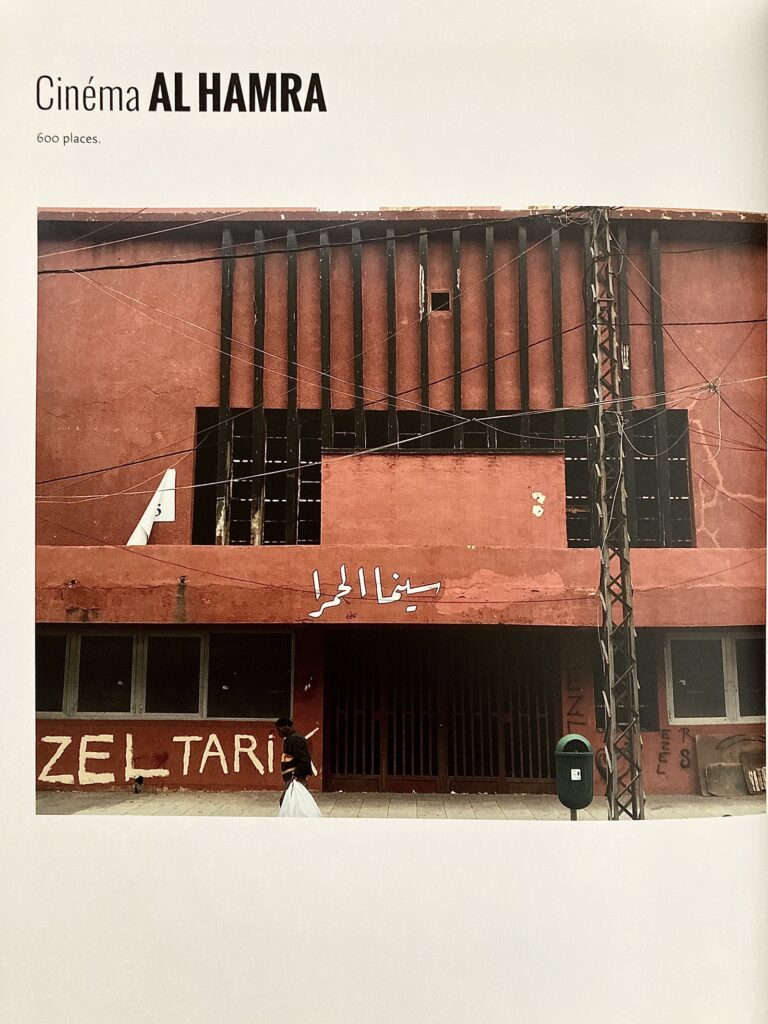

The gradual and never clear transition towards the after. “The oral memory that we didn’t bother to pass on to our children, so factious and sharp in the conscience of those of us who survived, those who stayed and those who returned,” he says. And yet, Antoine tells me with his hands now loose but always wrinkled, always lived, and his incredulous eyes, for a while people continued to live as if nothing had happened. He shows pictures of the cinema Odeon, the Cairo, the Zahraa, the Métropole, the Diana, the Empire in Downtown. The Capitole, the Grand Théâtre, the Opéra, the Rivoli, the Sheherazade, in Bourj. And then in Hamra, the Etoile, the Montreal, the Eldorado, the Clemenceau, the Coliséè.

And for each one, a story. About the Piccadilly cinema he remembers the first screening, it was 1965 and there was Doctor Zhivago, or the time a baby cried and the mother couldn’t get him to calm down, and that man from the hall who yelled at her to give him some milk to shut him up. And he laughs, Antoine, with that mixture of modesty and guilt and terrible nostalgia.

Photos and illustrations from Antoine Kabbabe’s book, La dernière séance (2022)

Photos and illustrations from Antoine Kabbabe’s book, La dernière séance (2022)

Photos and illustrations from Antoine Kabbabe’s book, La dernière séance (2022)

Photos and illustrations from Antoine Kabbabe’s book, La dernière séance (2022)

Talking with him is like jumping into a past we’ve only heard in movies, and we harshly realize did happen in reality. His stories are full of sparkling details that it is hard to believe true, especially in today’s Beirut, whose electricity is shut down because of the last economic crisis. Antoine’s words really seem to come from another world. If the same film was shown in Bourj and then in Hamra, for example, the scene would start 45 minutes late because the reels were carried by two guys on scooters who shuttled between theatres. And if they happened to be late for some reason – traffic or an accident – the spectators would start to complain. The disturbance was part of the atmosphere: “of course we went to the cinema to watch a film, but we also enjoyed ourselves and socialized, and let ourselves go.”

“But the biggest hubbub, screams and whistles were at the sight of a French kiss or a somewhat naked woman.” The noise came with eroticism. Yet they showed nothing, he admits. “Have you seen Nuovo Cinema Paradiso, by Giuseppe Tornatore? With the priest with the bell, and the censorship, it was the same.” Or: since the screenings used to be preceded by Les Actualités françaises, it was not uncommon to see certain spectators applauding when they saw the Pope or Charles de Gaulle on the screen; when the others doubled their enthusiasm at the appearance of Gamal Abdel Nasser. “Even then, before the war broke, Christians and Muslims had different sensitivities,” he jokes.

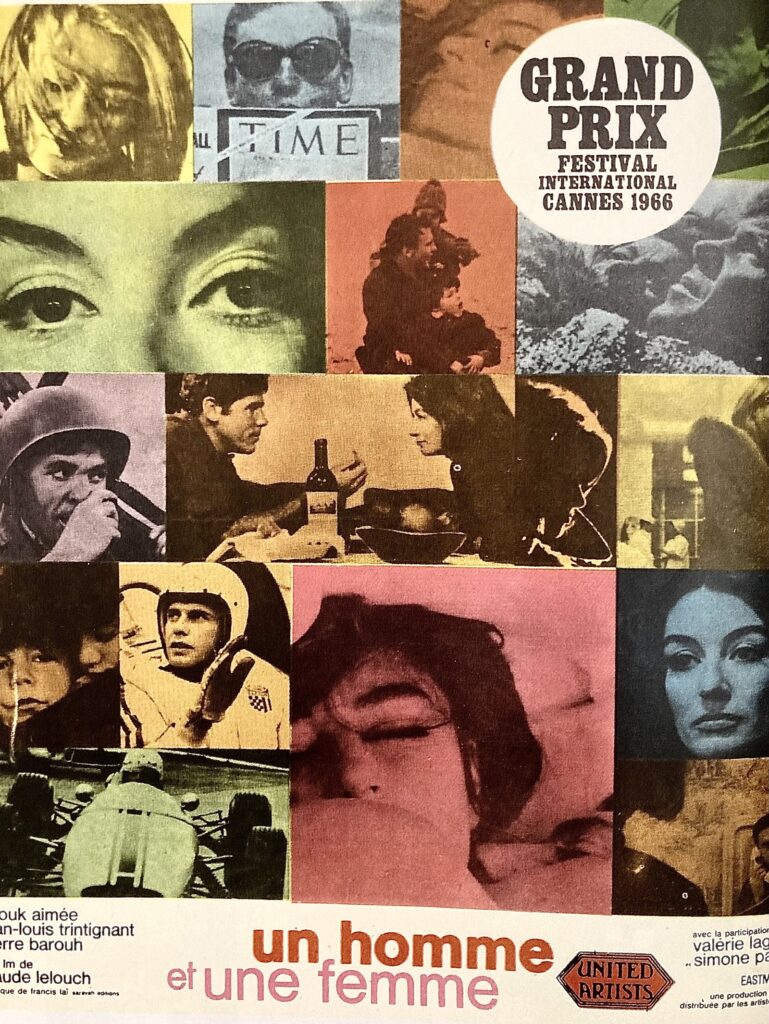

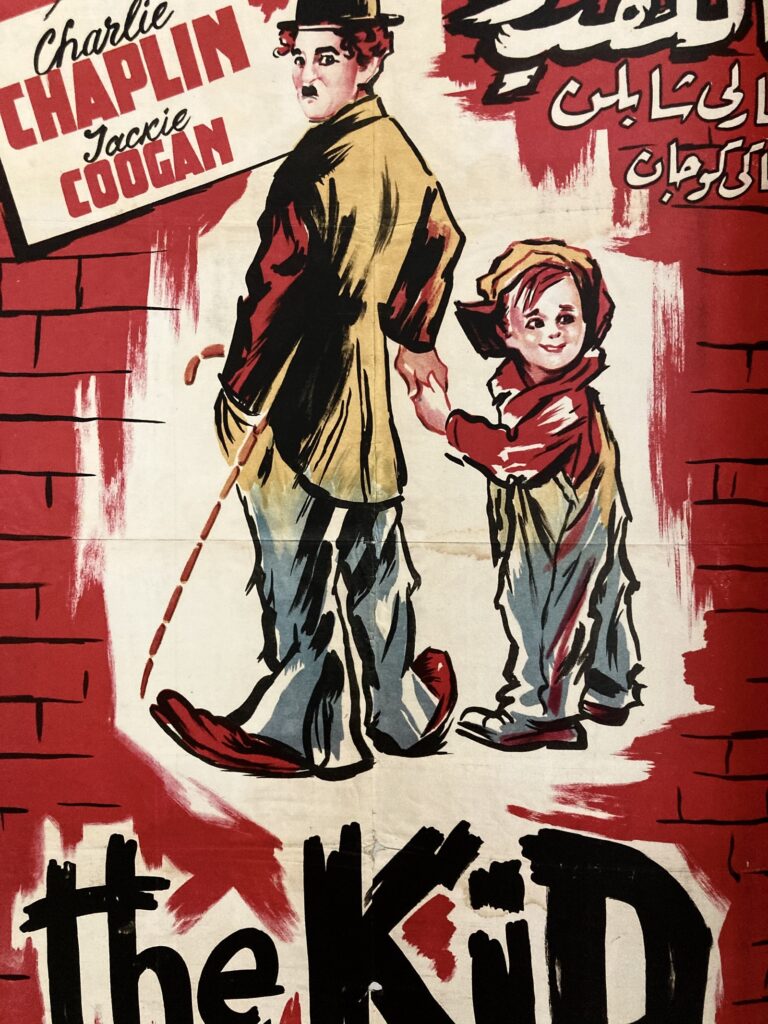

Cinema posters from Antoine Kabbabe’s book, La dernière séance (2022)

Cinema posters from Antoine Kabbabe’s book, La dernière séance (2022)

Yet the spaces were shared, even if the communities were separate, like when we went to uncle George’s once a week. “It was during the 1950s, and we weren’t used to watching movies: we’d rather listen to them on the radio on Saturday afternoons. They were Egyptian films full of singing and playing. But uncle George had a projector, he rented it for a few liras, and in his living room with very high ceilings and pointed arch windows, he screened films, with images, for the extended family. At the foot of the hill on which the house stood, a camp of Kurdish refugees who had survived Turkey.” One day, Antoine must have been five or six years old, uncle George was late, and a little girl had come knocking. “Lesh, why hasn’t the movie started yet? Over there we are waiting,” she wondered. Dozens of Kurds, in the field at the foot of the hill on which the house turned into a cinema stood, peered at those projections through the glass. Sharing.

These and other stories within La dernière séance, the last scene of Beirut through the eyes of a 25-year-old whose future has been ripped away and now, as his wife reproaches him, persists in living in the past. And he, the 25-year-old who is about to turn 76, is very proud of it.

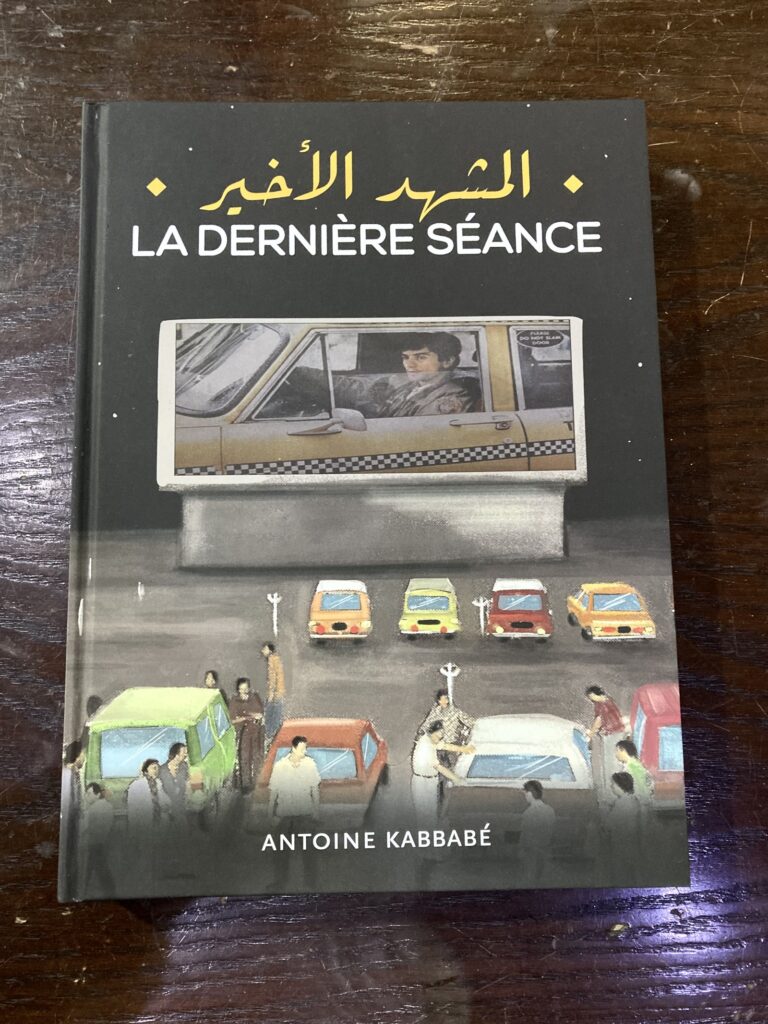

Antoine Kabbabe’s book, La dernière séance (2022)

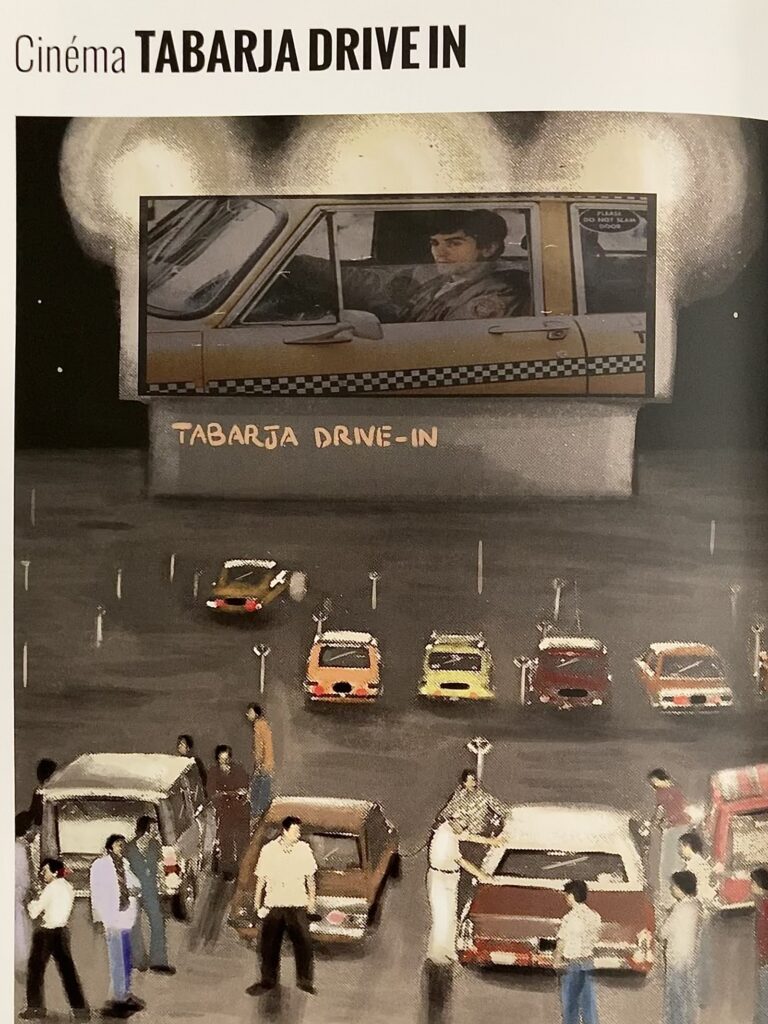

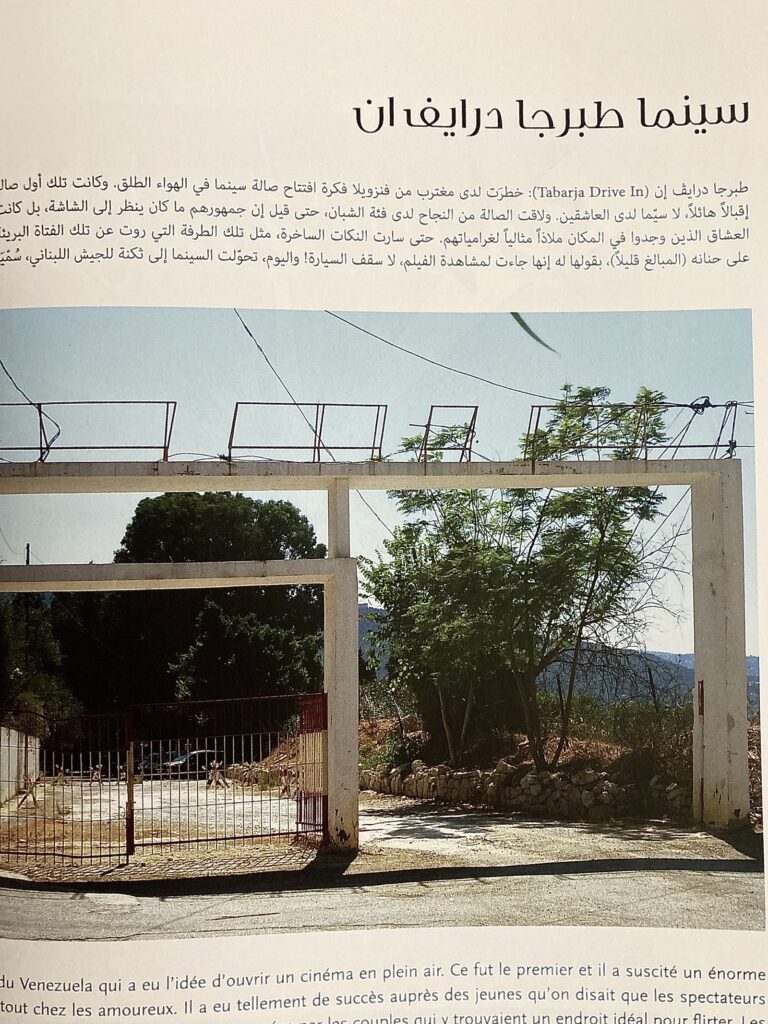

On the cover, the image of a drive-in cinema in Tabarja, on the road to Byblos. Antoine often went there as a kid, at fifteen or sixteen, he took his girlfriend at the time, he tells me, and he saw all the cars wobbling, do you know why? He asks me. “The couples, you know, they liked to have fun.” Couples, in Beirut, liked to have fun. He explains it to me with a mixture of guilt, embarrassment and terrible nostalgia: the gaze of that teenager whose embarrassment, guilt and amazement the war has robbed, leaving him alone with tons of hanin, the Arabic for nostalgia. Tabarja, page 356 and 357. Before and after. On the left, cars parked in front of the giant screen with the iconic face of Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver. On the right, the barred gate of a Lebanese army barracks. It is called, today, ‘barracks Drive in,’ in Arabic characters and English pronunciation.

It was an immigrant from Venezuela who had the idea of opening an open-air cinema: as the first in the country, it was so successful, especially among lovers, that they would soon build many more around Lebanon.

Before and after of drive-in cinema Tabarja, from Antoine Kabbabe’s book, La dernière séance (2022)

Before and after of drive-in cinema Tabarja, from Antoine Kabbabe’s book, La dernière séance (2022)

63 places, among neighborhoods and cities, photographed: a before and an after. The unclear but gradual caesura took place around 1975. 225 cinemas. Today abandoned and decaying buildings. He mentions Giuseppe Tornatore and his Nuovo cinema paradiso. “When we saw it, we said to ourselves, it was us, it was our story. We wanted to share it and we didn’t have the space.”

Lebanese cinema life was not interrupted by the war: instead, it was transformed little by little. At first, by moving from district to district, moving away from the green line which divided East Beirut from West Beirut in the fifteen-years-long war; then transplanting to the suburbs, into increasingly large and brutal buildings, more similar to shopping malls than to uncle George’s house.

“This book,” Antoine tells me, curling up his hands, “is the fruit of a love story.” Of a mad love for cinema. It is not a conventional history book. It is the story of a man falling in love with the seventh art, the cinema that drove him to the streets of Lebanon to rummage through time and space in search of broken dark rooms. Of lost cheer nuggets. Of gramophone music and prostitutes and innocence mixed with guilt and amazement. Of someone’s shouting when telling a woman to breastfeed her child to shut him up, while a boy sells Coca Cola in the stands, and you’re eleven years old, and there’s a smell of thick smoke, and you bet on volleyball games to earn 60 piasters needed for a ticket for a screening in Bourj on Thursday afternoon, demi-journée d’école à cette époque.