After a six-year hiatus, Lebanon’s museums open their doors for free during acclaimed ‘Night of the Museums’

You could have maybe seen such a queue outside Beirut’s National Museum in photos taken a few years after the end of the Civil War, when the mathaf– on the edge of the Green Line that used to divide the city’s Eastern from its Western sector – was considered one of the most dangerous places in one of the most violent cities in the world. Snipers were positioned inside and around the building to pick off people even when guns were supposed to be silent – and occasional ceasefires were opportunities to cross that imaginary line to fetch supplies in the East, then hope the truce would last long enough to race back to the West.

The scene outside Sursock, by contrast, recalled a more recent reopening – the one in spring 2023, when, after a three-year closure for extensive repairs following the 2020 Beirut Blast, the historic villa welcomed visitors to showcase the museum’s own history – something more than the mere artworks it contained. Just as if both the end of the Civil War and the reconstruction that followed the port explosion were being celebrated as occasions to bring the Lebanese closer to the history of a torn country, witnessed, if not appreciated through the palimpsest of a building. A museum – after all – is nothing more. A box that shelters past history, from the inside – yet outside, exposed to the current events, ultimately becomes another piece, another curio, an evidence, trace, the vestige of yet another era.

A total of 24 museums across Lebanon – mainly in Beirut, as well as in Saida, Jbeil, Tripoli and Jounieh – turned into monuments on the night of Tuesday, July 29, when they opened their doors for one night of free public access: to all. ‘Monument’, from the Latin word monumentum, derives in turn from the verb monere, which means to remind, to warn – and ultimately from the Proto-Indo-European root *men-, to think. A monument, therefore, is a memorial – something that reminds, or makes you think. A monition, if you want. The National Museum, as well as the USJ Minerals’ and Prehistory ones, and its Oriental Library – memento of the Civil War; Sursock and the AUB Archaeological Museum – of August 4; the Banque du Liban – of the economic crisis that in 2020 made people regret the war and the explosion: “because at least back then we could afford eating,” as many of my interviewees have told me in the past years.

But the night of Tuesday didn’t follow any catastrophe to commemorate, nor its end to celebrate. A war has happened, true, and in some areas it is still happening: yet neither the archaeological site of the Temples in Baalbek, nor the hippodrome of Tyre; not the Crusaders’ castles of Beaufort, Tibnine, Shaqra and Chamaa; not the Ottoman markets and houses – like those, almost completely razed to the ground, of Nabatieh – were included in the event, to get a glimpse of what it means, for a piece of national history, once again, to survive an attempt of erasure.

On November 25, 1997, the then President of the Lebanese Republic, Elias Haraoui, inaugurated the Beirut National Museum’s ground floor and a portion of the basement. Source: The National Heritage Foundation

After extensive renovations following the damages caused by the Beirut Blast, inside and out, the Sursock Museum reopened on May 26, 2023. Source: AD Middle East

The ‘Night of the Museums’ was re-established this week for the first time in six years. From 7 pm until 11 pm, with buses shuttling visitors around Beirut, the National Museum, Sursock, AUB Archaeological and Geology Museums, USJ Minerals and Prehistory ones, its Oriental Library, the Banque du Liban Museum, the Gallery of the Institut Français du Liban, Villa Audi, and the Nuhad Es-Said Pavilion for Culture, have seen lines of visitors, undeterred by the humid summer heat, waiting up to two hours in line to participate in the event.

Outside of Beirut, then, joining museums were, in Tripoli, Saint Gilles Citadel Museum; in Jbeil, the Aram Bezikian Museum of Armenian Genocide Orphans, the Byblos Site Museum, the Marine Fossil Museum, the Pepe Abed Foundation, MACAM and LAU’s Louis Cardahi Foundation; in Jounieh, the USEK Museum; and in Saida, Debbane Palace, Khan al-Franj, the Soap Museum, Hammam al-Jadeed, and Khan Sacy.

Museums as places of gathering

Across the Roman columns of the National Museum – built in the pharaonic style of the Egyptian Revival, from the nineteen-thirties – a 3D projection unfolded, illuminating stone with animated scenes from Lebanon’s past. The projection ended with a musical tribute to Ziad Rahbani, whose death just days ago left the country in mourning. “This year, Minister Ghassan Salameh was keen to revive the initiative not only to reopen the museum doors – but to symbolically reopen public access to culture,” said Nadim Choueiri, the Ministry’s lead curator. “The event is free and open to all, and this accessibility is key.”

Yet, the usual ticket’s price for each Lebanese visitor is only 50,000 LBP, a symbolic amount to push locals closer to the understanding of their past. In line – children, elders, youths, some of them visiting the hall’s collection for the first time. “It is not because it’s expensive or I cannot afford it,” said Layla, 21 years old, amazed in the middle of an unusually crowded Damascus Street. “But I never find time. This place is something I consider always there, it doesn’t move, so I’ve been postponing this visit for years. But this night will not happen again until at least next summer, I couldn’t miss it,” she admitted.

Turned, from cultural places, into vibrant hubs of social connection, Lebanon’s museums have shown that, beyond being precious monuments, they are also places of gathering. In a city that lacks public spaces, whose historic centre has been violated by privately-led real-estate project Solidere, the entrance to a gallery, the garden in front of Sursock, the impassable street that for fifteen years was inhabited by nothing but sniper bullets and their omnipresent surveillance – which had become green with vegetation growing undisturbed – as well as the centre of Downtown, in Rue Banque du Liban, reduced to flames by the 2019 protests, for one night, transformed into squares and meeting places for Lebanese people of all ages and sects.

Then, inside, the magic unfolded. From timeless pieces in the permanent collection – Phoenician sarcophagi, Roman mosaics, porcelains, Islamic calligraphies, and Ottoman coins – to temporary installations, such as Alfred Tarazi’s Hymne a l’amour, a multi-layered maze spotlighting Lebanon’s often overlooked heritage of craftsmanship through the lens of the artist’s own family’s artisanal legacy. 19th-century carved wooden door frames, Baghdadi ceiling panels, copper and brass vessels and coloured glass lanterns, in varying states of decay, which Tarazi inherited from four generations of ancestors – making their way into the place they’re supposed to be: a museum. As the testimony of a time when embellishing one’s place was common practice, and now is no longer: obsolete objects, brought back to life for a contemporary sensibility through childhood pictures, private memories, intimate sensations, family anecdotes – all of which lead to the central figure. The mother.

Hymne a L’Amour is an installation taking place between two spaces: the National Museum of Beirut and an abandoned hangar in its vicinity. In this installation, Tarazi deals with a wide range of objects inherited from his family’s century old business in oriental craftsmanship. Wood, copper, glass and other materials in varying degrees of degradation are presented to pose the stepping stone towards the creation of a museum of decorative arts in Lebanon. Source: Alfred Tarazi

The Tarazi family has contributed some of the most intricate decorative work found in the Sursock Palace, Villa Linda Sursock by Le Bristol, and the Sursock Museum, along with hundreds of other Ottoman-era structures across the region. Today, their legacy continues, with architect Camille Tarazi leading the restoration of Sursock Palace’s wooden doors and elements – originally crafted by their ancestors – that were damaged in the 2020 Beirut port explosion.

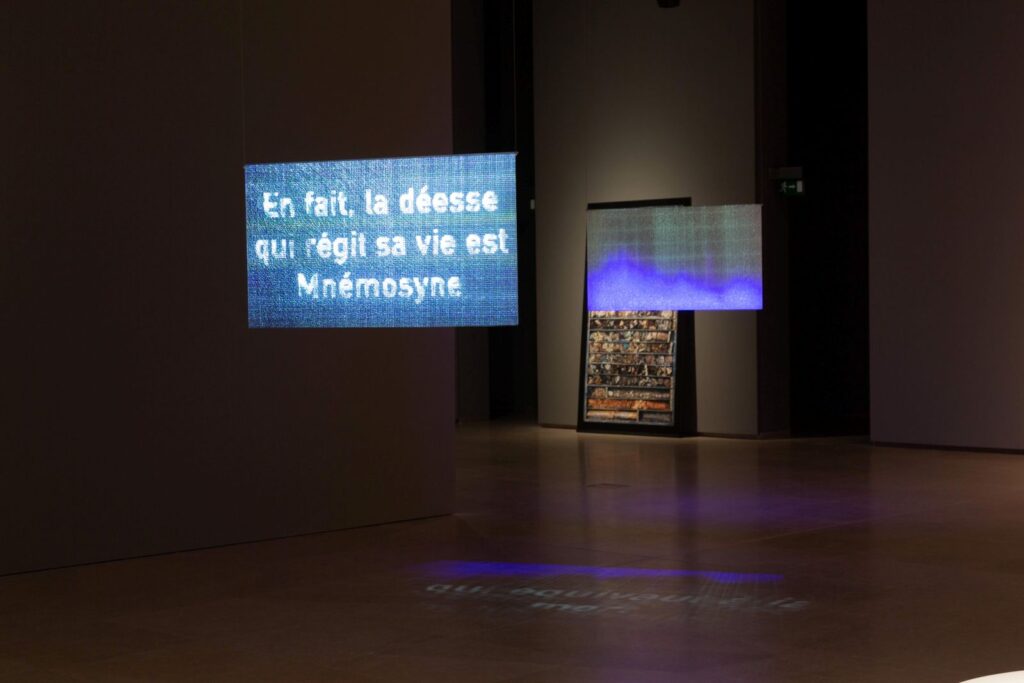

There, at the Sursock Museum, filmmakers and artists Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige have turned history into their metaphorical medium in a new body of work that brings together nearly a decade of multimedia creations. Running alongside a retrospective of their films at Metropolis Cinema, Remembering the Light stems from in-depth research and collaborations with archaeologists, geologists, and historians. Despite their international acclaim, this marks the Lebanese duo’s first solo exhibition since 2012 – a rarity, as noted by curator Karina al-Helou, which flows naturally from the historical narrative presented at the National Museum. With roots tracing back to Palestinian, Greek, and Syrian refugee families, in their ‘manifesto of fragility’ Hadjithomas and Joreige grounded their work firmly in Lebanese heritage, using their deep sense of narrative to shape a wide-ranging and reflective collection. Originally conceived before the 2020 Port explosion, the show was re-envisioned in its aftermath to reflect on how art can offer transcendence in a world of endless promise.

Sursock’s exhibition Remembering the Light, curated by Karina El Helou. Credits: Christopher Baaklini, Courtesy of Sursock Museum

Even the AUB Archaeological Museum suffered significant damage in the August 4, 2020, Beirut explosion. Most devastatingly, much of the glass collection at the University’s Archeological Museum – located about three kilometers from the epicenter – was reduced to dust: toppled a critical showcase containing 74 well-preserved archaeological glass vessels from the Early Roman, Byzantine, and Islamic periods. Thousands of glass shards from the precious vessels were mixed up with the glass from the showcase panels and shelves and from surrounding broken glass windows. All but two of these priceless, irreplaceable artifacts were shattered.

This was the ‘baptism of fire’ that kick-started Dr. Nadine Panayot’s tenure as AUB Museum Curator, the museum’s website reads. Out of the 72 glass artefacts that had been thrown to the floor, the team managed to restore 28, eight of which were sent to the British Museum to be pieced back together and then featured in an exhibit, The Shattered Glass of Beirut, which drew in record-breaking crowds before traveling to China and Japan.

The broken remains of glass objects and the display case in which they were exhibited, on the floor of the AUB Archaeological Museum, after the explosion at the port of Beirut on 4 August 2020. Photo: American University of Beirut

Is there therefore added value for an artwork that, in addition to the time that consumes everything, has survived a catastrophe? A piece of glass from the Byzantine era mixed with glass from the era of corruption, the crafted detail of a wooden door made deeper by the splinter of an explosion, the mosaic of a pastoral scene disfigured forever by the gaping hole caused by sniper fire? What is certain is that visitors to the Lebanese ‘Night of the Museums’, last Tuesday, could not help but come across these other fragments of history, the scars of which are still visible on their facades. A museum, after all, is also a witness.

A view shows a mosaic artefact that was damaged by a sniper during the Lebanese civil war, at the National Museum of Beirut. Credits: REUTERS/Mohamed Azakir