Speaking out against Russia’s ongoing attack on Ukraine is not a violation of political neutralism.

Standing with the embattled Ukrainian regime’s defense of its territory and sending humanitarian aid to the over one million refugees that have fled does not discredit disassociation.

And opposing the violation of another country’s independence is the right of any state that adheres to positive neutrality.

There is a misunderstanding of the meaning – and merits – of neutrality, especially in the Lebanese context. We should take a position on external violence when necessary (like Ukraine) and proactively refuse its rippling effects at home.

That is the core principle of positive neutrality: not taking military sides in external conflicts.

When Lebanon’s neutrality (once, or twice) shined

This is summarizing at best, but on March 25, 1959 and in the midst of heightened Arab nationalism – while half of Lebanon’s population yearned for a cementing of Arab ties and even union with Egypt and Syria’s United Arab Republic – our president, Fouad Chehab, refused Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser’s entry into Lebanon, and instead met him at the border with Syria.

Chehab maintained ties with Nasser throughout his presidency, and did not challenge Egypt’s ascendancy. But he kept Nasser’s vigorous Arab nationalism at bay, and Lebanese nationalism void of military-like coercion.

Fast forward to June 1967, when Egypt, along with Syria and Jordan, fought Israel in a Six-Day War that changed the region’s map once more. Egyptian forces were pushed out of the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip (and Nasser resigned three years later); Syria lost its strategic Golan Heights; and Jordan its control over the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

As for Lebanon? We are rarely mentioned in that war because no bullet was fired – in either direction – across our southern border.

The fallout of 1967 tore Lebanon apart in the years thereafter. An emboldened and armed Palestinian presence took hold, and with the arrival of Fatah and the PLO following the 1969 Cairo Agreement, Lebanon’s nascent positive neutrality ended.

But in a parallel universe, and one I would wormhole my way into had physics limits permitted, let us reimagine a Lebanon that avoided that path to civil war and paralysis.

No Arafat

We would have supported the Palestinian cause on our terms. Not Yasser Arafat’s.

That would require reconciliation with demographic demons and ending existential insecurity. A long-called for senate would have offered us one step in that necessary direction. Mosaic-minority uncertainty is real and remains unaddressed. And that centuries-long journey of communal power-sharing to modernity would have finally started, including a granting of full economic access and political rights to Palestinians no longer refugees, and a residency void of third-class prejudice or citizen prevention.

Palestinians in Lebanon, like Armenians before them – and Palestinian Christians given preferential treatment – all belong to this country. To extrapolate from Samir Kassir, Lebanon’s 20th-century experience would have been represented by shared prosperity rather than collective ruin.

No Israel

Ultra-right-wing nationalists and pseudo-intellectual anti-Palestinian activists (despite all their efforts) misinterpret neutralism. Their understanding implies hostility to Palestinian self-determination and willful ignoring of historic injustice.

You can criticize both Syria’s Assad and Israel’s occupation and violence while refraining armed involvement from either neighbor.

Lebanese have every right to stand in solidarity with any suffering population. Refusing to recognize Israel ahead of a wider Arab accord in line with the 2002 Arab Summit, either on colder terms like Jordan and Egypt’s long-standing relations or more recent and warner ties à la the United Arab Emirates, is not a violation of neutralism, either.

There is no advantage in pursuing a diplomatic channel on our own that invites further destabilization, vast resentment and political unrest. Instead, mitigating the conflict’s repercussions begins at home. If Palestine matters, it is the Palestinian people that deserve their dignity, not the armed struggle or the unforgiving road that took Arafat through Jounieh on his way to Jerusalem. Inviting that conflict into Lebanon ensured the breakdown of state authority, collapse of our army and a militia vs militia scenario that can cripple any country to despair.

The Lebanese and Palestinian causes can coexist. They both deserve their pursuit.

This will likely run contrary to public opinion, but I think the Israelis would have had no self-proclaimed legitimate reasons to violate our airspace to this day, and in recent memory, invade without hesitation.

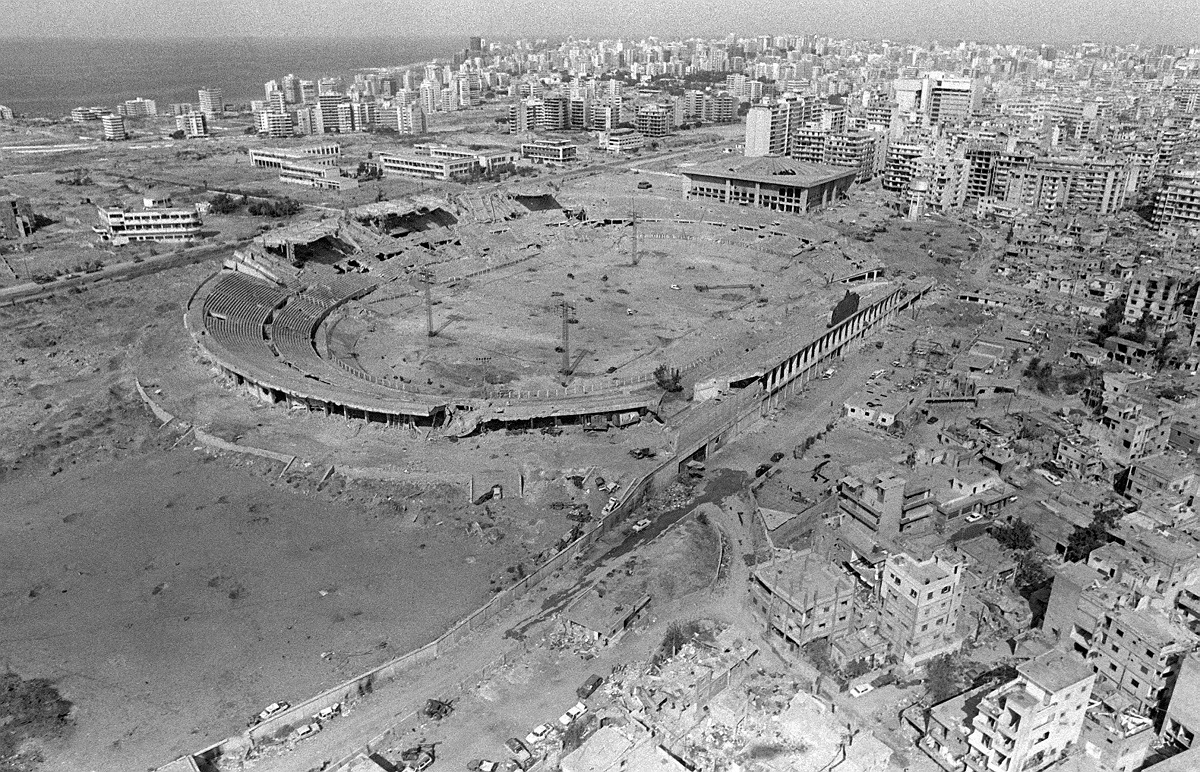

Neither in late 1969 when they first occupied the south beyond the Litani, or in 1982 when they laid siege to Beirut. That includes April 1996 and July-August 2006, in their fierce clashes with Hezbollah. And without an armed PFLP presence in the late 1960s or any non-state actors’ attacks emanating from Lebanon thereafter, we would have avoided immensely disproportionate retribution.

Including losing thirteen Middle East Airline aircraft at Beirut’s airport, in 1968, to Israeli attack.

Increasing calls to negate positive neutrality are misreading its purpose. And today, amidst Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s plight, we should condemn Putin’s actions without letting his determined invasion, or any external confrontation, enter our borders.

I am not giving the Israelis a pass. But I am insisting that political solutions are necessary to find an answer to the Palestine question (and an end to the Arab-Israeli conflict), and those are well beyond Lebanon’s reach.

The political violence attached to those causes should have never found sanctuary in Lebanon.

No Saudi Arabia

Jumping ahead, to a more recent and heightened rift that has shattered our part of the world.

Irrespective of Iran’s current hegemony over our foreign policy decision-making, internal security matters and Hezbollah’s undisputed role as status quo enabler and IRGC interlocutor (I have written extensively on those issues in this column), there is no reason for Lebanon to host regional disputes.

Saudi Arabia’s substantially declined influence did, at one point, dampen and even damage local calls for independence. Their vested interests did nothing in the long run to upend Iran’s order. The Saudi regime even pushed former prime minister Saad Hariri to apologize to Bashar al Assad in 2010, in Damascus, on behalf of March 14. A forced acceptance of a short-sighted proposal to bring Assad out of Iran’s orbit.

Why would we want to return to the 1990s? When given a choice between Assad’s influence and the IRGC’s intrusion, the March 14 movement stood no chance. Saad Hariri, himself, paid that steep political price, culminating in his renewed exile.

No Iran

Without the IRGC’s armed relationship with Hezbollah, we would have a diplomatic channel with Iran. State-to-state relations afforded to countries without proxies dictating politics.

Tehran can boycott us as often as Riyadh. They can sanction us when they deem necessary, and send our ambassador home. But that ambassador would leave having represented Beirut’s interests in Tehran. There would be no self-anointed ambassador like Hezbollah serving two diplomatic posts at once – Iran’s dictates in Lebanon and Lebanon’s adherence to Iran.

Neutrality would guarantee neither Iran’s proxy-army nor any other country’s inclination into our geography. The 2012 Baabda Declaration (signed and ignored by Hezbollah) would insist on our military disassociation from the Syrian war. No Lebanese foot soldier would have died defending the Assad regime or fighting for his demise.

Vladimir vs Volodymyr

Lebanon’s dependence on wheat imports from both Ukraine and Russia, aside, we play no direct or indirect role in Vladimir Putin’s pending siege of Kiev. That our foreign minister unexpectedly described the Kremlin’s attack as an invasion is of little to any relevance to Russia, and the almost forgiving tone from Russia’s ambassador to Lebanon implies no immediate political repercussions.

Fallout will inevitably arrive from a Putin-backed Assad regime emboldened to seek further sway in local affairs. As well as Lebanese actors turning to Damascus for their own political survival.

This will determine the future of what opposition to Tehran’s influence in Beirut looks like – neither independent nor local. Rather, on Bashar al Assad’s terms, serving as instigator and conflict-resolver (the role his father patiently crafted).

That has already begun. We could avoid that path if we borrowed from recent history: the late 1950s to late 1960s, defining our short-lived positive neutrality, and a decade that helped independent Lebanon shine.

Increasing calls to negate positive neutrality are misreading its purpose. And today, amidst Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s plight, we should condemn Putin’s actions without letting his determined invasion, or any external confrontation, enter our borders.

Ronnie Chatah hosts The Beirut Banyan podcast, a series of storytelling episodes and long-form conversations that reflect on all that is modern Lebanese history. He also leads the WalkBeirut tour, a four-hour narration of Beirut’s rich and troubled past. He is on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter @thebeirutbanyan.

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOW.