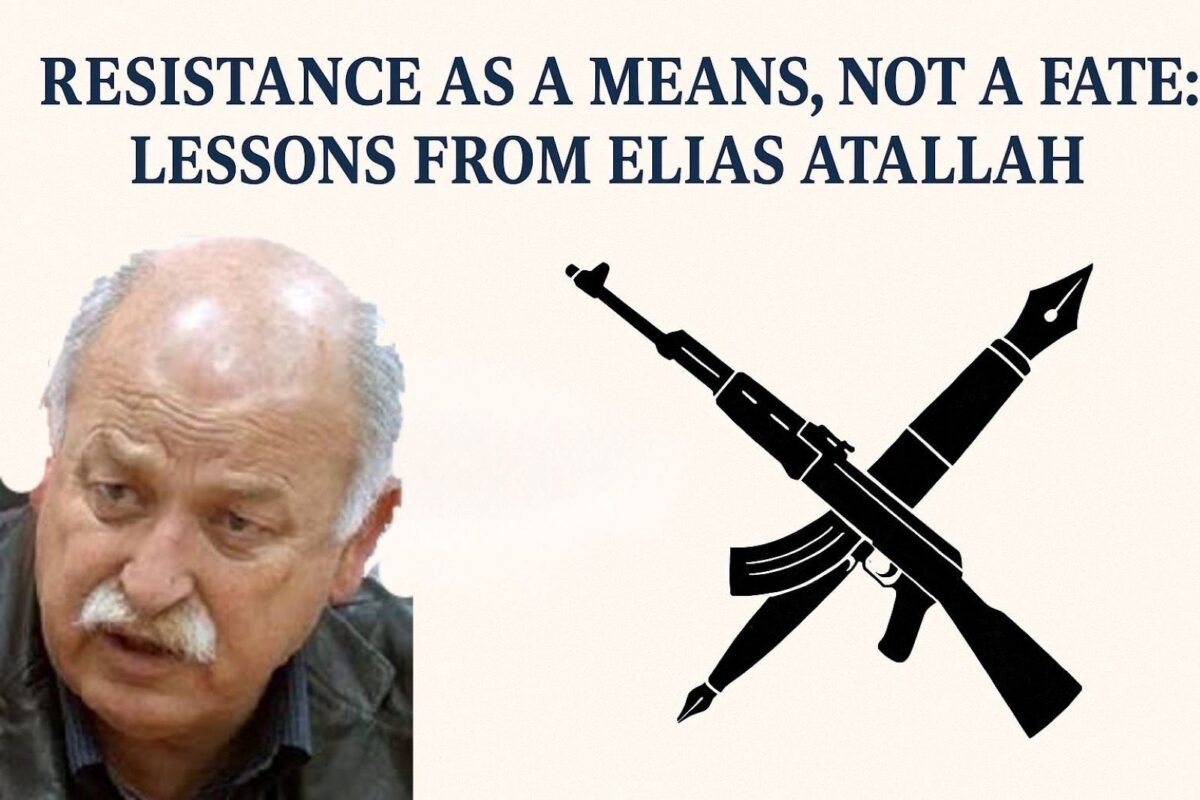

The interview with former MP and coordinator of the Lebanese National Resistance Front (Jammoul), Elias Atallah, is not a nostalgic recollection of a bygone era. Rather, it is a public exercise in reconciling with the past. In his narrative, three values stand out—values glaringly absent from Lebanon’s present: self-criticism, the ethics of resistance, and clarity of purpose when wielding force. These are not intellectual luxuries; they are the conditions for distinguishing between a resistance that liberates and then steps aside, and one that turns weapons into a profession and the country into a hostage.

Atallah and his comrades admit that they made mistakes, that war is not destiny, and that major decisions—from Tripoli to other fronts—were sometimes driven by faulty judgments or dubious calculations. This admission is not an act of self-flagellation, but the foundation of a new political awareness: that heroism is not measured by bullets fired, but by the ability of an experience to critique itself and change course. Many who moved from armed struggle to peaceful political work carried with them this question of responsibility, rather than hiding behind the excuse of “circumstances.

The story of Souha Bechara and her attempted assassination of Antoine Lahd, the head of the South Lebanon Army who collaborated with the Israeli occupation, is not a passing detail in the memory of war. In Lebanese perception, Souha’s name became synonymous with courage and defiance—a young woman entering the home of the commander of the South Lebanon Army and opening fire on him. But in Atallah’s account, another face appears: the ethical caution against resistance degenerating into vengeance without limits. For him, the issue was not Souha’s bravery or loyalty, but the deeper question: can we treat a home with a wife and children as we treat a military target? Is it permissible to conflate enmity toward an occupier with the sanctity of family and human relations?

Atallah’s objection was neither technical nor military, but human and ethical. In doing so, he opened the door to a debate absent in militant culture: resistance is not measured solely by its military outcomes but also by its ethical standards. Without those standards, the line between resisting occupation and practicing terrorism becomes dangerously thin. Souha reminds us of the individual’s willingness to risk life for a cause, while Atallah’s testimony reminds us that the cause itself loses its meaning if not governed by the balance of values and humanity.

For Atallah, the goal was clear: liberate the land and hand it over to the state. Anything beyond that belongs to politics, which must be settled in institutions, not at gunpoint. Here lies the rupture between the “old” and the “new”: those who today present themselves as heirs to the resistance discourse—the followers of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard in Lebanon—did not liberate a state to return it to its citizens. They professionalized weaponry to impose guardianship over society and the state, assassinated opponents and former resistance fighters, and destroyed Lebanon’s urban fabric, economy, and their own Shiite community in the process. In their hands, “resistance” morphed from a circumstantial means into a permanent identity; from a defensive duty into an open license for killing, repression, smuggling, and laundering ruin. This is no liberation project, but a war economy.

The interview also sheds light on the meaning of fair memory: there can be no heroism without accountability, no narrative without victims’ rights. Critiquing the experience does not negate its sacrifices; it protects them from trivialization and prevents martyrdom from becoming a blank check to justify lawlessness. This is where transitional justice acquires practical meaning: acknowledgment, political apology, and the reform of institutions hijacked in the name of “resistance.”

The significance of Atallah’s testimony is that it redefines courage. Courage is not firing in Hamra Street at an arrogant occupier, but the ability to say “we were wrong” and to step back when the means become a burden on the goal. Courage is to separate foe from enemy, to reject merging resistance with intelligence agencies or transnational militias. Courage is to affirm that the state alone holds the legitimate monopoly over organized violence, and that any weapon outside it is not resistance—even if wrapped in its slogans—but an assault on the social contract.

From this angle, Jammoul’s story is a lesson in the limits of force. Yes, there were operations that hurt the occupation army and forced its withdrawal from Beirut. But the deeper value does not lie in “counting” operations; it lies in the conclusion: there is no resistance without an ethical compass, and no compass without a state. When regimes of tutelage—Syrian yesterday, Iranian today—confiscate the decision of arms and their direction, resistance falls from its national pedestal to become a tool of hegemony.

Lebanese who wish to escape the cycle of violence must reclaim the terminology. “Resistance” is not a registered trademark, nor an exclusive right of a sect or axis. Today, those who resist are those who defend the constitution, judicial independence, a productive economy, and Beirut’s right to live without rocket launchers on its rooftops. Those who hijack the state and monopolize decisions of war and peace are not resisting; they are crippling the very possibility of a nation.

Atallah’s interview places us before two choices: to remain prisoners of a discourse that confuses martyrdom with blackmail, or to restore the value of critique and accountability—just as he and his comrades did when they chose peace and political engagement. In a time when weapons have become an “identity,” we must return the phrase to its original meaning: resistance is a means, its end is the establishment of a free and just state; everything else is merely another form of occupation.

This article originally appeared in Nidaa al-Watan

Makram Rabah is the managing editor at Now Lebanon and an Assistant Professor at the American University of Beirut, Department of History. His book Conflict on Mount Lebanon: The Druze, the Maronites and Collective Memory (Edinburgh University Press) covers collective identities and the Lebanese Civil War. He tweets at @makramrabah