When U.S. envoy Tom Barrack described Lebanon as a failed state and its leaders as dinosaurs, outrage spread fast. Politicians condemned his tone. Commentators called it arrogance. And social media flared with accusations of Western condescension.

But the truth is, the real insult to Lebanon isn’t what was said. It’s what’s been done to it.

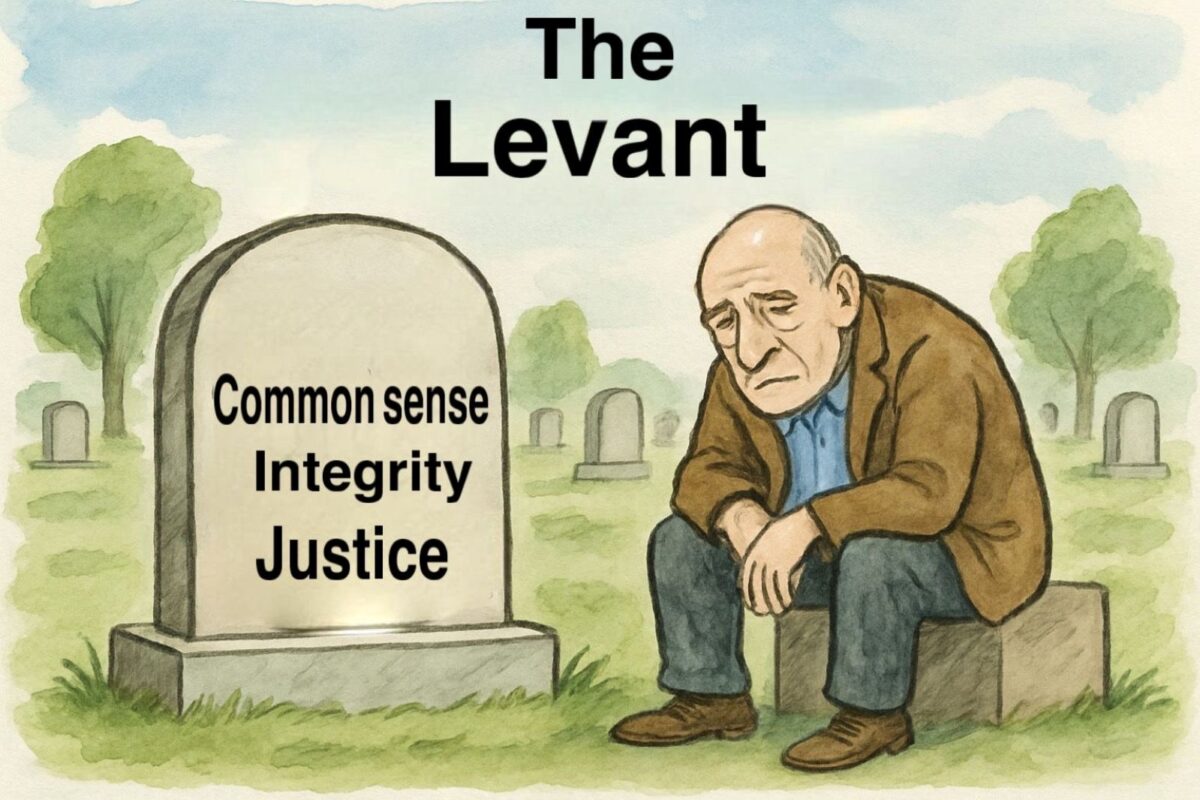

For decades, our leaders have emptied the state of meaning while pretending to embody it. They turned public service into personal business, institutions into party branches, and reform into a slogan. They presided over a currency collapse, a banking implosion, a judiciary in paralysis, and an electric grid that flickers like a dying candle. Yet somehow, the national outrage burns brighter when someone names the failure than when we live it every day.

That says something about our collective psychology.

Patriotic fragility

In social psychology, groups that experience chronic failure often react defensively when outsiders point it out. They feel their identity attacked and rush to defend the symbol even when the substance is gone. It’s easier to shout at the mirror than to look into it.

Lebanon’s reaction to Barrack was a textbook case of that: we rejected the messenger rather than confronting the message. It’s a form of what I call patriotic fragility; loving the homeland so much you can’t bear to admit how badly it’s been betrayed.

Barrack’s metaphor of “dinosaurs” was not random. He was describing a political class that belongs to another age. One that governs through sectarian arithmetic, patronage, and paralysis. When he followed that with “Lebanon doesn’t need to jump to landline but straight to Starlink,” he was making a deeper point: our problem isn’t only corruption, it’s mental obsolescence.

The paradox of pride and paralysis

And yet, many Lebanese immediately complained: So now we have to submit to American will and technology?

As if the problem were Starlink, not state failure.

Who exactly do we think we are fooling? The same people crying “sovereignty” are the ones importing generators, buying American phones, using Western social-media platforms, and educating their children abroad; because our own system can’t produce or sustain anything functional.

We reject their innovation while we can’t even manage a power grid in a country the size of a city elsewhere. We fear “submitting” to foreign technology while depending on it for every aspect of modern life. It’s the purest form of hypocrisy: we curse the systems that work, while defending the politicians who broke ours.

The real submission

In the rawest terms I say: Lebanon has already submitted. Not to America, but to incompetence, clientelism, and fear of change. Every hour of blackout, every hospital unpaid, every young person forced to emigrate is an act of surrender.

We’ve submitted to the idea that things cannot change; that the old guard must stay, that reform is naïve, that hope is dangerous. Those are the real chains, not some foreign envoy’s metaphor.

Barrack’s remarks may have been blunt, even arrogant. But arrogance doesn’t make them false. The choice before us isn’t between sovereignty and Starlink, it’s between extinction and evolution.

If our leaders are dinosaurs, it’s because we’ve kept them alive long past their age of usefulness. And the longer we defend their fossils, the less of a country we’ll have left to save.

Ramzi Abou Ismail is a Political Psychologist and Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Social Justice and Conflict Resolution at the Lebanese American University.

The views in this story reflect those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of NOW