After eighteen years since its foundation, and five of nomadism due to the economic crisis, the Metropolis association opens a new cinema in the centre of the capital: a sign of return and a new beginning for the seventh art that Lebanon so strongly needs, finally in a physical space

TEXT:

It is from the title of the first documentary screened after last Saturday’s opening, The Third Rahbani, about the musical successes of Elias – the last of the Rahbani brothers, to whom the greatest success would have come, despite the initial and widespread mistrust that he would have grown in the shadow of Assi and Mansour – that the new opening of the Metropolis cinema is to be baptised, the third: after the 2006 war and the 2020 crisis had aborted the first two of its experiences.

From war to crisis and from crisis to war, the adventure of the Metropolis association is parallel to that of Lebanon. Founded in 2006 to fill the cinematic void left by the civil war and both the Syrian and Israeli occupations, it was launched in the small hall of al-Madina theater in Hamra on July 11, on the eve of the outbreak of yet another Israeli war on the country. The space had time to the first projection only. The day after, it was transformed into a shelter for displaced people: and in order to keep the children safe inside, the team started showing them films, making the young people’s exposure to cinema the core of its mission.

Reopened in 2008 in its two halls of the Empire-Sofil center in Achrafieh, until their 4closure in January 2020 due to the economic crisis, then been nomad for almost five years, the collective has been working combining educational projects for children with the ambition of a national archive, the Cinémathèque Beirut. Initiated in 2018 to continue its work in archiving Lebanese cinema, and currently hosting 500 films and the digitization of magazines, articles and cinema posters, it stood as the bastion of preserving and making accessible Lebanon’s cinema heritage, in the absence of an official body that takes charge of it. And that’s why many filmmakers, beneficiaries, or other interested film enthusiasts, have decided to do it themselves, as was the case for Jocelyne Saab or Maroun Baghdadi – whose cinema can be undoubtedly referred to as a pillar in the history of Lebanon.

The only missing piece of a place of preservation and consultation, but also exchanges and reflection, was to finally become a space: public, and physical. Today, that space has now finally come, in a lightweight and modern structure built on a vast plot of land in Mar Mikhael, donated directly across from the site of the catastrophic Beirut port’s blast of August 4, 2020, with the possibility of being dismantled if necessary, and therefore mobile. Designed by the architect Sophie Khayat in an extremely symbolic spot in the city’s history – yet which lot of land, in Beirut, is not densely charged with major events’s emblems – this landmark cinema features two indoor halls, one with 200 seats and the other with 100, alongside an outdoor screen, a garden with a café, and a full-fledged film library acting as a resource center, with its more than 3,000 works dedicated to the seventh art, as well as the Metropolis film archives, including the Lebanese film archives. Another, powerful way of preserving part of Lebanese national memory, only a few steps away from the still unreachable sea: the port being occupied by the devastation left by the explosion.

The entrance of the newly-opened Cinema Metropolis, Beirut. Photo credits: Valeria Rando

A time to rebirth

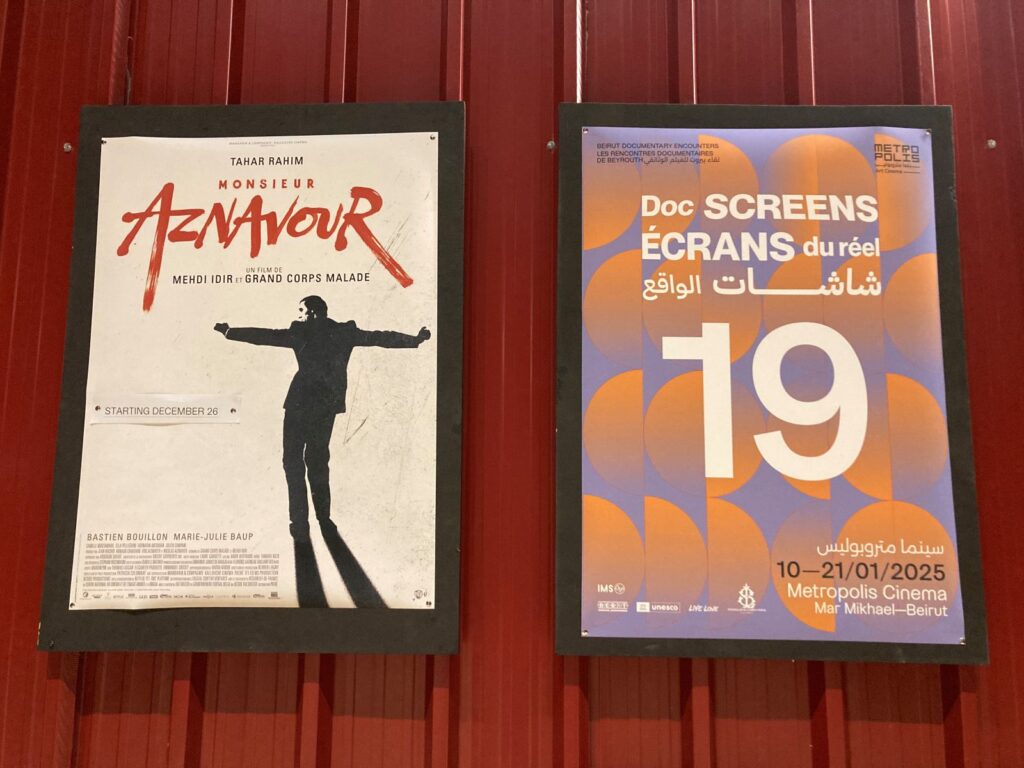

On the fringes of the commercial programming of the usual circuits, rather focused on blockbusters and other mainstream works, the halls of the Metropolis have been, in this sense, the first arthouse in the region: a platform for Lebanese films when commercial cinemas refused to screen them. Their rich and eclectic programs, combining a series of festivals that have become essential over the years – despite the nomadism – including the European Film Festival, the Écrans du réel dedicated to documentaries, Beirut Animated and the Youth Film Festival, to which were added the resumption of prestigious festivals such as the Semaine de la critique, but also partnerships with Arte or Les Cahiers du cinéma.

But beyond its screening rooms, the Metropolis Association, co-founded by Hania Mroué and chaired by Zeina Sfeir, has worked since 2006 to promote and support independent Lebanese, Arab and international films, to encourage young audiences to discover cinema through regular cycles, to establish a rich and varied program in partnership with local and international actors, and to finally promote access to cinema for all. In short, to give the seventh art the place it deserves in Lebanon, and more generally in the region.

Next screenings and festivals’ posters displayed at the entrance of the newly-opened Cinema Metropolis. Photo credits: Valeria Rando

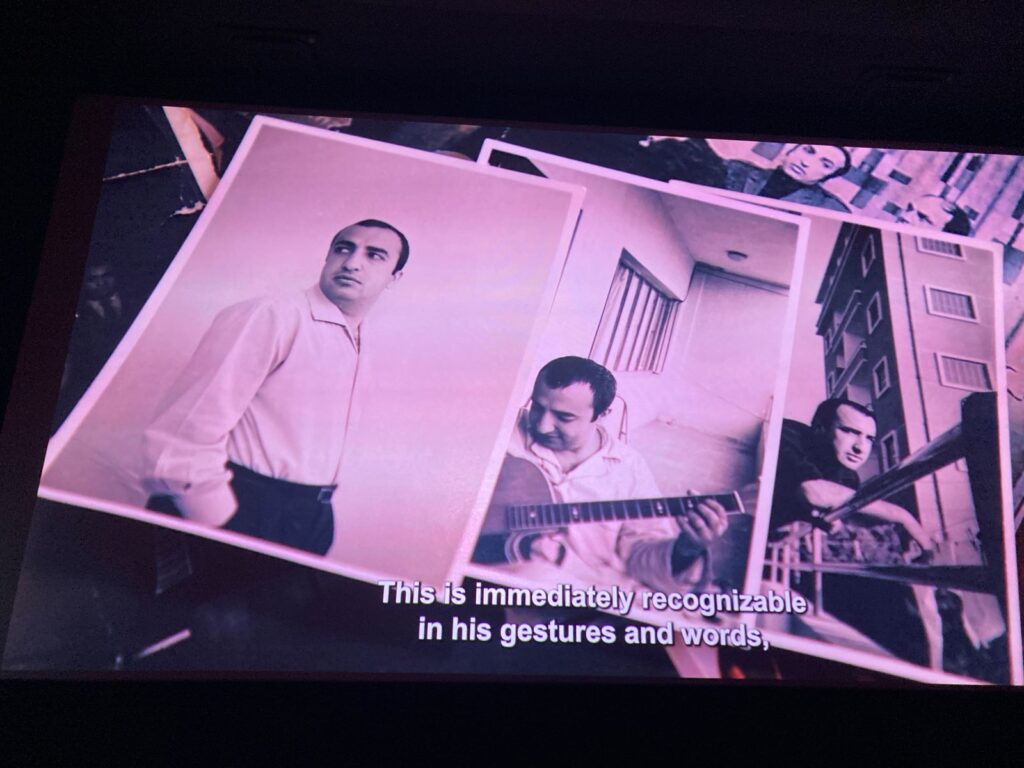

A shot from the Al-Jazeera produced documentary The Third Rahbani, directed by Feyrouz Serhal, projected on December 23 in the newly-opened Cinema Metropolis. Photo credits: Valeria Rando

The inauguration that took place last Saturday – a gala cine-concert featuring a montage of vintage shorts from Arab archives accompanied by live music composed and performed by Anthony Sahyoun – was postponed from mid-October due to the violent escalation of Israel’s aggression on Lebanon, and has now come amid the ongoing ceasefire, despite fragile, following months of air strikes and artillery attacks: as the rumbling of thunderstorms still terrorises generations traumatised by more than one war, and the political upheaval in neighbouring Syria – just freed from the stranglehold of the Assad regime, which also had a grip on art, especially film – gives hope for the proximity of new stories to be filmed and projected. And in this dance between crossing history and escaping from it, the importance of the return to physical space must first be emphasised. In the era of streaming platforms, of social distance sanctioned by the pandemic and not yet abolished, of expensive multiplexes in shopping centres, outside cities, the return to the movie theater and the collective experience of watching – and crying, laughing, humming, breathtaking together – opens horizons and perspectives at a time when in this part of the world, these can seem limited.

Yet today, in a Beirut still uncertain whether or not it has emerged from war, the time has come for rebirth. Through the images, stories, narratives that it deploys, cinema allows other possibilities of returning, opening different angles and mastering the play of light. And just as in the eponymous film by Fritz Lang released in 1927 after which the association is named – the megacity imagined in 2026 in a dystopian society – ending with a symbolic reconciliation between the inhabitants of Metropolis after all the divisions and chaos, Lebanon’s cinephiles want to hope that fiction whispers to reality, and that this time will last. As a cinema hall in a city as Beirut isn’t just a movie theatre: it’s also a refuge for many dreams, aspirations, and ideas, reviving culture and uniting people through the love of cinema even amid destruction and despair. Yet not necessarily putting despair and destruction at the center of the lens.

During last year’s edition of Écrans du réel festival, in the spring of 2023, dedicated to documentaries, the unlikely audience moved by the memory of crises, deaths, and constant injustice – and who still had no idea what was to come in a few months – wondered what Zakaria Jaber’s cinema shared with that of Abbas Fahdel, what the furious cries of Samaher Alqadi had in common with the long, measured silences of Maya Abdul-Malak, with her Lost Heart and Other Dreams of Beirut, beyond the mastery of the editing, the spare subtlety of the dialogue. And it was perhaps this realization: that the emptiness left by disappointed illusions is all the more bitter than that of the dead. That what did not have the opportunity to be, leaves more suffering than what was, and is over. At the time, the specter of war seemed more distant than the reality of crisis and revolution, and the martyrdom of a protest, the burial of an ideal, forced documentary cinema to come to terms with the frustration of an aborted hope, the regret of wondering how it would go, the irrevocable fatality of the ‘if’, the beginning of a hypothetical period nipped in the bud, containing in germ the failure of ‘when’ declined to the future: and this, to be buried, seemed all the more arduous and painful.

If and how the genocide in Gaza, the war on Lebanon and the Syrian revolution will change the way we narrate the present, it is still too early to tell: now that the act of burying and digging up has become physical again, and the static time of great disillusions seems to have been suspended, leaving space for history. That what could have been has been, beyond limits: and much more. Still, it won’t be hazardous to say that the desire to tell has not died: as the one which drives one to gather in a cinema hall on a rainy winter’s day.

A year and a half ago, when that hall was nomadic and cinema d’essai an abstract space – to be cut out among the posters of a cultural center, or in the hours interspersed between one appointment and the other – those documentaries born in Lebanon and for Lebanon, we liked to think of them not ‘about’ it. But within it. With the ambition to tell the world as it found itself the day after yet another catastrophe, calling the audience in the auditorium to question art on what it will do next, how it will know how to tell this one, of reality. Even this, for cinema, has not changed: although answers have changed radically.

Looking at the debut of winter 2024, it is not surprising that the most exuberant musical output of the third Rahbani occurred in the 1970s and 1980s: at the peak of the Lebanese civil war. That when Sami Clark proposed to Elias to compose a piece for a singing competition in Germany in 1979, despite the depression over the conflict, inspiration came, and Mory Mory was born, winning the first prize. Elias Rahbani criticized artists who complain of a lack of creativity. Inspiration is a muscle and must be exercised, he said: and one might add, so is going to the cinema. One must make an effort, despite the rain, despite the depression over the conflict. For when we watch a documentary that for once is not about war but about music, and at the mention of the anecdote that Rahbani composed the Baath Party anthem under Hafez al-Assad, there is no longer disappointment, but a bitter levity. If only to witness the burst of laughter from the unlikely audience, two weeks after the collapse of a 54-year repressive regime: it is worth it. Even if only to say: it is past. The war, the dictatorship, the time when there was no cinema in Beirut. It is past. Forced by the rain to linger at the entrance, humming the melodies of Sabah, Melhem Barakat, Wadih Safi, Fairouz, Majida El Roumi, Nasri Shamseddine, being surprised that only one man composed them all, the one who was thought to be ‘the third’, the least talented, in atrocious and unforgettable years. And for once, not thinking that the storm is an explosion, but that it is just a storm. And the melody remains.

A shot from the Al-Jazeera produced documentary The Third Rahbani, directed by Feyrouz Serhal, projected on December 23 in the newly-opened Cinema Metropolis. Photo credits: Valeria Rando