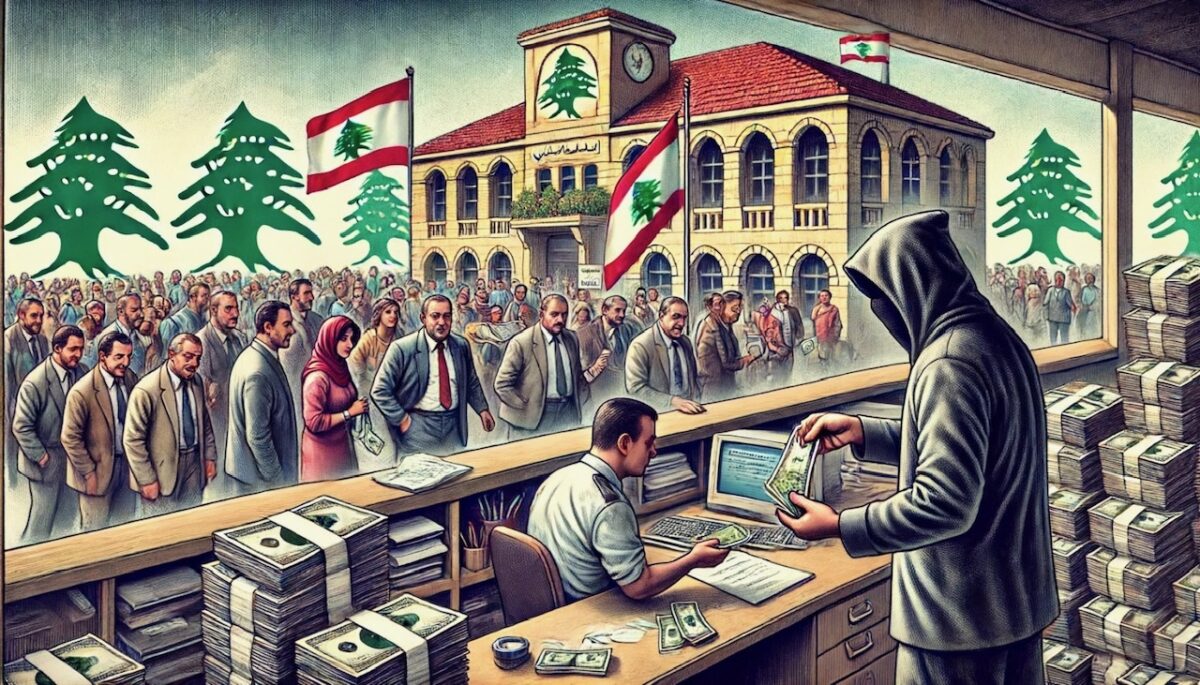

Treasury loses some 1.5bln USD in black market and gratuities services

Lebanon public servants have totally embraced the “gratuities” system, you might think this is old news for a country like Lebanon , well it’s not the same as ever.

Corruption in Lebanon has involved billions of dollars. The UN (2001) corruption assessment report on Lebanon was one of the earliest documents that illustrated starkly the scale of corruption in the Lebanese Institutions and its devastating impact on the economy. It estimated that the Lebanese state squanders over US$1.5 billion per year as a result of pervasive corruption at all levels of government (nearly 10% of its yearly GDP).

It has featured senior political leaders and their cronies using government ministries and offices as individual fiefdoms to enrich personal fortunes. Those were cited in the famous Pandora Papers and other criminal charges. The political elites who run powerful ministries hand out lucrative contracts to private companies either owned by themselves, their families or allies, who are required to give enormous financial kickbacks in return. A study published by Chatham House in June 2021 found a lack of transparency in the awarding of contracts for major infrastructure work going back decades. Public utilities such as Port of Beirut and borders control all seem to have been a prey to that. An IMF report quoted that since 2018, total revenues have collapsed catastrophically from 21 percent of GDP to 6.3 percent in 2022. In that time, despite high levels of inflation and a dramatic reduction in real wages, the public servants that remain in their posts have done so with high workloads and, particularly in tax administration, in unsuitable, poorly maintained facilities.

Institutionalizing the gratuities system

The end of the civil war permitted the reinvention of warlords responsible for violence as democrats in a sectarian power-sharing government. Now these warlords have “institutionalized” the “gratuities” system as power sharing is meant to give guarantees of representation to Lebanon’s various sects in government and the public sector. No caution and perhaps no shame is there. Nasser Saidi, a former minister of economy and trade and vice-governor of the Banque du Liban (the central bank), described Lebanon as a ‘rare combination of an experienced kleptocracy and a kakistocracy’ – a political system that has not only been ruled by a corrupted political elite, many of whom have used public funds as their personal purse, but which has also ensured that a significant number of incompetent and unqualified individuals have been entrusted with the management of governmental affairs. The Lebanese parliament has introduced some counter-corruption measures in recent years, namely the passing of several anti-corruption-related laws, and in May 2020 the government adopted the National Anti-Corruption Strategy.

With the collapse of the economy in 2019, “gratuities” became part of the income of a civil servant an employee or soldier. The speed at which your application is processed would put Usain Bolt to shame. Which means legislating it, even in the absence of a clear legal text. The Lebanese government was unable to increase the salaries of the military and public sector employees, so it allowed the intensification of the “gratuity” system, where everything became “paid.” The Lebanese government encourages its huge bureaucratic body to secure its income however it agrees, as long as it is almost “bankrupt” and cannot pay decent salaries.

In a country where bureaucracy moves at a pace akin to molasses in January, one peculiar phenomenon stands out as the secret sauce to expedited service: tipping. Lebanon has cracked the code on how to navigate its labyrinthine civil administration—it’s not about who you know, but how much you’re willing to slip under the table. From registering your land to applying for a passport, and even buying stamps, the art of tipping has become as essential as breathing in this land of cedar trees and traffic jams.

Land Registry Office

Let’s start with the illustrious Land Registry Office, where dreams of property ownership go to languish in paperwork purgatory. Imagine you’ve finally saved enough of your hard-earned liras to purchase a plot of land. You stroll into the office with your meticulously prepared documents, ready to embark on the journey of becoming a proud landowner. But wait, what’s this? The clerk seems to be staring at your papers as though deciphering an ancient cuneiform tablet. Hours pass like days as your file languishes on his desk, gathering dust and disdain. Suddenly, a glimmer of hope—a discreet cough from the person behind you. Ah, the seasoned Lebanese whisper: “Time to tip, my friend.”

You cautiously slip a few bills into the palm of the clerk, whose demeanor miraculously transforms from indifferent bureaucrat to efficiency personified. Suddenly, stamps are stamped, signatures are signed with newfound vigor, and your dreams of property ownership are resurrected from bureaucratic purgatory. As you leave the office, slightly lighter in the wallet but immeasurably relieved, you can’t help but marvel at the power of the Lebanese tip.

Legitimizing gratuities

With the economic collapse and the collapse of facilities that provide services to the Lebanese due to corruption, strikes, employee absence, and judicial arrests in real estate departments and the “beneficial” department, the state began to legislate, even without a clear legal text, the issue of receiving tips in all fields. Knowing that these “gratuities” or bribes wear a different, special character in each facility.

An example of that is going through any

Next on our tour of bureaucratic wonderlands is the Passport Application Office—a place where time stands still and patience wears thin. Picture yourself in a serpentine queue that seems to stretch into infinity. The air is thick with the collective sighs of resigned citizens and the faint scent of falafel wafting from nearby street vendors. Hours tick by as you inch closer to the window of hope, where a harried civil servant awaits your fate.

Applying for an urgent passport, would cost an additional 4 million and 900 thousand liras this is justified by citing the absence of appointments, and sometimes through intimidation about the length of time it takes to issue a regular passport.

Car Registration authority saga

As in public security, so in other institutions concerned with providing services to citizens, including the car registration authority known as Al-Nafi’ah, for example. A source familiar with what is happening in Al-Nafaa reveals that previously, tips were generally paid in order for the broker to process transactions quickly. If the ordinary citizen wants to clear his transaction himself, he will be able to do so, but it will take a long time, due to the complex procedures and the “hallways” of the utility buildings. Today, he cannot do that, as the “tip” has become a necessary condition in order to begin processing the transaction. Without paying it, the citizen will have to wait a week in long queues.

When Al-Nafia was “dismissed”, the Lebanese were hopeful of better treatment, but they soon returned to reality to discover that the situation had become worse. Bribery has become a basic condition for obtaining services. According to the source, to clear the transaction the tip needed ranges from 50 US dollars for a small service, to 200 dollars for the service of registering some cars. Tips are divided among employees, a small share for the broker, and the largest share is for others.

There are also sums of money that citizens pay without receiving receipts. Which means that it is paid from outside the official system, and it is not known how it is spent or the identity of who receives it. Among these amounts is one million liras in exchange for obtaining a “vehicle inquiry form,” that is the request to know the legal status of the vehicle, knowing that information regarding this matter has been submitted to the judiciary.

All of this, in addition to what was said about the issue of electronic stickers, for which the citizen pays a million liras without obtaining them. A lot has been published about this issue in recent days, noting that a large number of tax payers did not obtain this sticker in previous years as well.

Money transfer companies

The Traffic and Vehicles Registration Authority announced the start of collecting annual traffic fees at all money transfer company centers (OMT-WHISH MONEY-CASH PLUS-BOB FINANCE) as of the beginning of this month. Citizens rushed to pay, in light of the security campaign carried out by the Internal Security Forces, and the payment system was repeatedly disrupted.

The official commission for OMT, for example, is Lp 20000, and the number is listed on the official receipt. However, there are some service provider agents who add their own commission of up to 200 thousand liras, in exchange for photocopying documents. !

Money transfer companies charge arbitrary commissions and fees. The commissions range between $6 and $7, while the mechanics fees on old cars are less than the value of those commissions. The commission for example in the “wish” company, is “zero”, as for BOB Finance, the commission for the transaction of paying traffic fees is Lp 30000, while agents ask for additional amounts as the price of ink for the printer or photocopying of documents!

In all cases, the “saw” of paying a commission, bribery, or disguised betrayal operates actively and feverishly in all departments of the state, as well as in everything related to intermediary services.

The tax stamp mafia

And let us not forget the humble stamp, that small but mighty symbol of bureaucratic validation. In Lebanon, even the act of purchasing a stamp can turn into a dramatic saga of waiting and wits. You approach the counter, where a stoic clerk guards a veritable treasure trove of stamps behind bulletproof glass. “I need a stamp for this document,” you say, handing over your papers with a hopeful smile.

All you get is a poker face back!

A Court of Audit report concerning tax stamps in Lebanon revealed that licensed distributors of stamps had illicitly made Usd20 million in profit over two years, exploiting an “orchestrated” shortage of stamps in the country.

Citizens are typically required to attach these stamps to various official documents as proof of fulfilling necessary tax obligations. The report’s authors proposed several immediate actions to rectify the market, including initiating a tender for implementing electronic stamps in place of the current ones in circulation.

Instead of dealing with the corruption of tax stamps per se the Finance and Budget Committee asked the Ministry of Finance to provide it with “specific numbers about the cost of the marking machine if adopting it instead of the paper stamp, the cost of the electronic stamp and other modalities.

The Committee chairman Ibrahim Kanaan disclosed that “the black market for stamps is draining 200 million dollars from the state treasury, as only 1,800,000 dollars will enter the treasury before the year 2023, totaling some 30 million dollars”.

Kanaan called for “activating 650 approved marking machines in more than one place in Lebanon, with regard to personal status and mukhtars, as there are procedures that need legislation, such as allowing the mukhtar and personal status officials to collect the value of the stamp or increase it over the transaction price. This legal provision is required to reduce theft.” Providing the market’s need for the paper stamp temporarily until work begins with the electronic stamp.

Implications

But what are the broader implications of this tipping culture on Lebanon’s economy and society? Economists, if they could stop rolling their eyes for a moment, might argue that tipping perpetuates inefficiency and encourages a parallel economy where favors are bought and sold like commodities on the Beirut Stock Exchange. The cost of services skyrockets as citizens are forced to pay extra for what should be their right—efficient and transparent governance.

Yet, defenders of tipping argue that it’s a necessary evil in a country plagued by political gridlock and economic uncertainty. “Tipping keeps the wheels of bureaucracy turning,” explains a seasoned bureaucrat who requested anonymity. “Without it, we’d be drowning in paperwork and drowning in despair.”

Meanwhile, civil society activists are up in arms, organizing protests and petitions against what they see as legalized bribery.

As Lebanon grapples with an economic crisis of biblical proportions—hyperinflation, currency devaluation, and a soaring debt-to-GDP ratio—the issue of tipping may seem like a drop in the Mediterranean Sea. But for ordinary Lebanese citizens trying to make ends meet, it’s a daily reminder of the uphill battle they face in their own country.

In conclusion, while tipping may grease the wheels of Lebanon’s bureaucratic machine, it also perpetuates a cycle of dependency and inequality. Until meaningful reforms are implemented to tackle corruption and streamline public services, Lebanese citizens will continue to pay the price—literally and figuratively—for a system that puts patronage above professionalism.

So the next time you find yourself in a Lebanese government office, grappling with the Kafkaesque absurdity of it all, remember the ancient wisdom passed down through generations: when in doubt, tip generously. It may not solve all your problems, but it’s a start. And who knows? With a little luck and a lot of cash, you might just get that stamp, that passport, or that plot of land you’ve been dreaming of.

Maan Barazy is an economist and founder and president of the National Council of Entrepreneurship and Innovation. He tweets @maanbarazy.

The views in this story reflect those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of NOW.