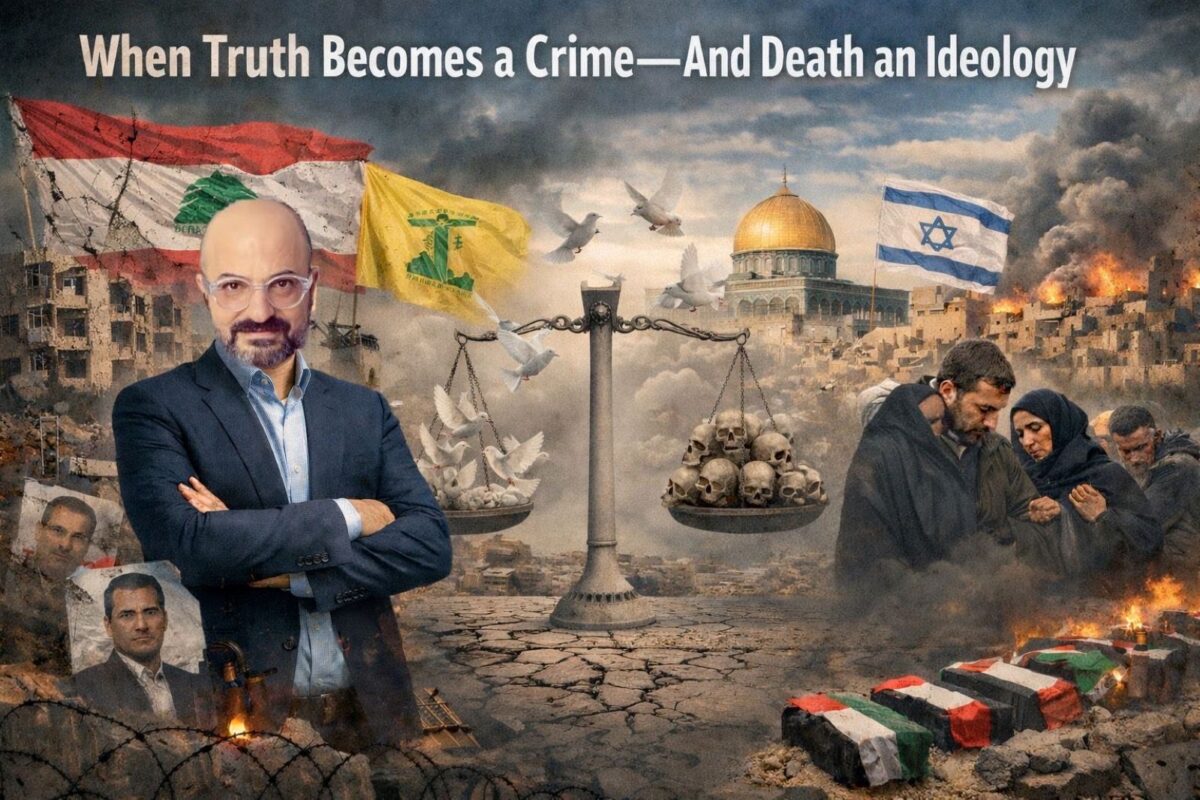

The campaign against Nadim Koteich, former General Manger of Skynews Arabia, is not a media quarrel or a professional disagreement. It is a political act that reveals something far more consequential: the inability of a self-described “resistance” ecosystem to tolerate dissent from within its own claimed moral universe. In this worldview, life has value only when it is instrumentalized, sovereignty is negotiable, and human beings matter only insofar as they can be converted into symbols of sacrifice.

Koteich was not targeted because he failed, nor because he misspoke. He was targeted because he crossed a red line: he rejected the monopoly over moral language. He called things by their names. The Assad regime is a regime that kills. Iranian tutelage in Lebanon is a form of colonial control. And the presence of illegal weapons outside state authority is not resistance—it is a structural curse. These positions are neither new nor opportunistic. They form a coherent political outlook for which Koteich has paid a recurring personal and professional price. The current campaign is simply its latest manifestation.

What makes this assault particularly cynical is its appropriation of Palestine. Gaza, in this discourse, is reduced to a rhetorical shield; civilian death becomes a mobilizing tool rather than a human tragedy. The same voices attacking Koteich today previously justified the obliteration of Aleppo, minimized chemical attacks, and framed Syria’s destruction as an acceptable cost of “steadfastness.” These are the same actors who insisted that the road to Jerusalem runs through Syrian mass graves. Their sudden concern for ethics, media standards, or moral consistency is difficult to take seriously.

The accusation that Koteich harbors an “affinity” for Israel follows the familiar logic of political blackmail in the region: discredit the critic by associating him with the ultimate taboo. Yet this narrative collapses under scrutiny. Koteich has never advocated violence against Palestinians nor defended war crimes. His actual offense was to argue that just causes are betrayed when they are transformed into mechanisms of perpetual self-destruction. He insisted that Lebanon is not a military base, not a refugee camp, and not a proxy arena for regional powers. Within an ideology that sanctifies death, such statements amount to apostasy.

What truly unsettled his critics was not only the content of his position, but its openness. Koteich spoke without euphemism, without ritualistic disclaimers, and without seeking validation from the very forces that once claimed moral authority while practicing mass violence. This defiance stands in contrast to a media environment that has normalized intimidation, selective outrage, and the laundering of brutality under revolutionary aesthetics—where one enemy is endlessly denounced, while the primary agents of violence are shielded by the language of “resistance.”

Koteich and others like him disrupted a core equation: that devastation equals heroism, that militias safeguard dignity, and that states are expendable luxuries. They challenged the premise that human lives are raw material for ideological projects. That challenge, more than any single statement, explains the ferocity of the response.

History, however, is not written by smear campaigns. Organized defamation can silence voices temporarily, but it does not determine moral reckoning. Those who defend life, however isolated, ultimately speak louder than the machinery of death.

Even if one grants that Koteich, like any public intellectual, has made errors, there remains a fundamental distinction. A flawed defense of statehood and civic life is ethically superior to ideologies whose coherence depends on mass displacement, silenced dissent, and the normalization of atrocity. The distance between the two is not one of professional judgment or political taste—it is a matter of basic humanity.

Nadim Koteich, for all his complexities, did not construct an identity around death, nor elevate destruction into doctrine, nor convert killing into sacred duty. That alone places him outside the system attacking him—and on the side of a history that will eventually distinguish between those who instrumentalized suffering and those who refused to sanctify it.

Standing where he does, Koteich has chosen—not rhetorically, but deliberately—the right side of history

This article originally appeared in Elaf

Makram Rabah is the managing editor at Now Lebanon and an Assistant Professor at the American University of Beirut, Department of History. His book Conflict on Mount Lebanon: The Druze, the Maronites and Collective Memory (Edinburgh University Press) covers collective identities and the Lebanese Civil War. He tweets at @makramrabah