As the war between Hezbollah and Israel rages on, speculation about a ceasefire continues to dominate headlines

Diplomatic channels are active, with US envoy Amos Hochstein expressing optimism about bridging differences. Yet, if history and current dynamics are any guide, the likelihood of a ceasefire remains minimal – at least before Donald Trump takes office in January. More concerningly, even if a ceasefire is reached, the absence of meaningful terms addressing Hezbollah’s disarmament risks plunging Lebanon into internal conflict.

Why a ceasefire before January is unlikely

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has little incentive to finalize a deal before January 2025. With Trump returning to the White House, Netanyahu anticipates a far more favorable US stance, particularly in terms of supporting Israel’s security narrative and its strategic objectives against Hezbollah. Agreeing to a deal under Joe Biden, who has prioritized de-escalation in the region, could be seen as a concession to an administration with whom Netanyahu shares a strained relationship.

Moreover, Netanyahu’s government is likely using this period to maximize military and political pressure on Hezbollah. The rhetoric of being “closer than ever” to a ceasefire serves as a strategic tool to manage international expectations while keeping all options open. This approach mirrors Israel’s dealings with Hamas earlier this year, where the promise of progress was followed by prolonged inaction.

The danger of a ceasefire without disarmament

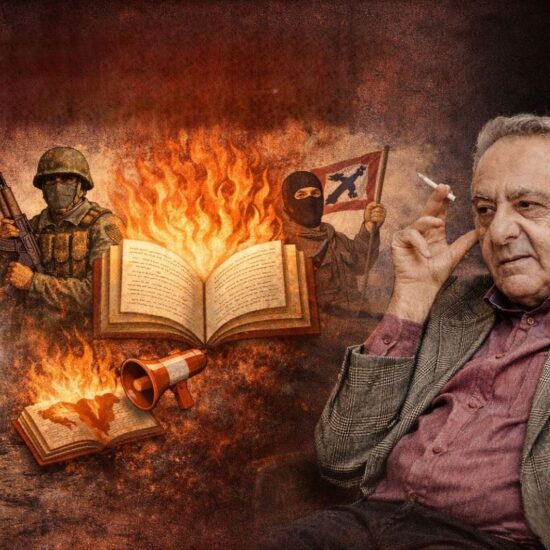

Even if a ceasefire is achieved, any agreement that allows Hezbollah to maintain its arms without addressing its role in Lebanon’s political and military landscape is a recipe for disaster. The Shia political faction, led by Hezbollah, will be grappling with significant losses – both militarily and in terms of regional influence. This loss will likely fuel internal anger and a need to reassert dominance, either through escalated rhetoric or political maneuvers.

At the same time, other Lebanese factions, many of which blame Hezbollah for the country’s decline, will resist its continued dominance. The notion that one faction can hold the nation hostage through ties to regional powers serving foreign agendas is no longer tenable. This creates a volatile dynamic where grievances, distrust, and competing ambitions could ignite internal conflict.

The shadow of civil strife

Lebanon’s fragile sectarian fabric has been tested repeatedly. A ceasefire that ignores the fundamental issues of national identity, power-sharing, and sovereignty risks reigniting these fault lines. The memory of Lebanon’s civil war looms large, and the conditions today are eerily reminiscent of those that led to the conflict decades ago: fragmented leadership, external interference, and a lack of a shared national vision.

As Hezbollah’s power is increasingly challenged, both by external forces and internal dissent, the potential for civil strife grows. Without a comprehensive resolution that includes disarmament and a reimagined national framework, Lebanon may once again find itself at the mercy of factions vying for dominance.

Lebanon stuck at a crossroads

The road ahead for Lebanon is fraught with danger. The current war has shattered the illusion of “coexistence” that masked deep divisions within the country. It has exposed the reality that Lebanon’s factions do not share a unified vision of the nation’s future. This moment demands bold action – not just from political leaders but from all Lebanese factions – to confront these differences and work toward a shared destiny.

Failure to act leaves the door open for external powers to shape Lebanon’s future according to their own interests, not those of its people. No action, in this context, is indeed an action—one that paves the way for division and possibly the fragmentation of Lebanon into multiple states. If Lebanon is to avoid this fate, the ceasefire, when it comes, must be more than a pause in hostilities; it must be the start of a genuine national reckoning.

Ramzi Abou Ismail is a political psychologist and researcher at the University of Kent.

The views in this story reflect those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of NOW.