A timeline of waste mismanagement and the spread of landfills along the coasts of Lebanon

When I interviewed the environmental engineer Ziad Abi Chaker, in his office in Badaro, on the last day of indiscriminate war before the curfew went into effect, with the echo of extremely violent bombings on Dahieh, we said to each other – as always when in Lebanon people try to raise awareness about the environment: every time there is a major crisis, the environmental issue becomes secondary.

And yet, in the aftermath of a very fragile truce, with displaced people on their way to what remains of the southern villages, the Beqaa Valley, and the southern suburbs of the capital, it is not secondary to wonder what will become of the mountains of rubble, decomposed animals, and rubbish that line the gutted roads.

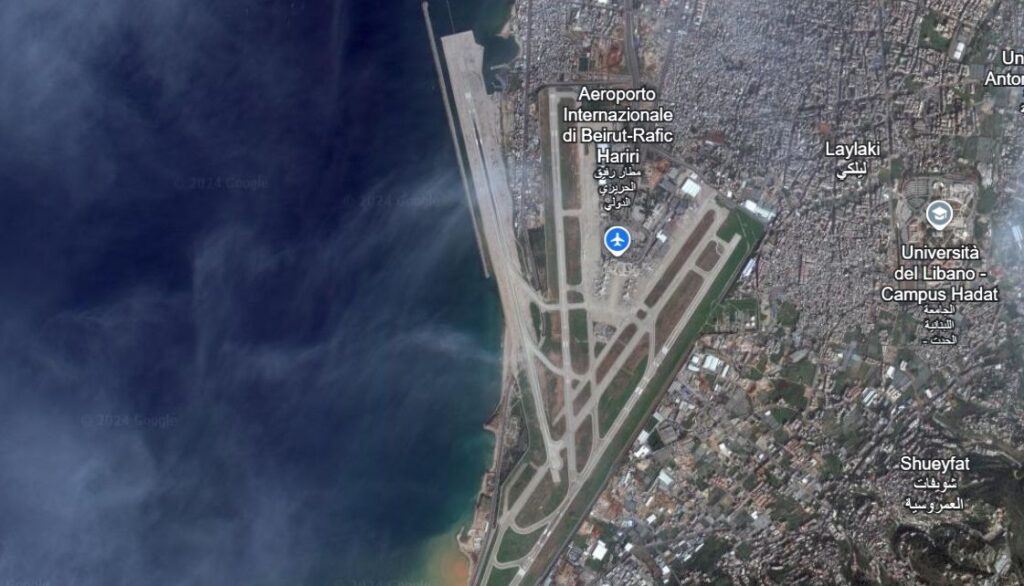

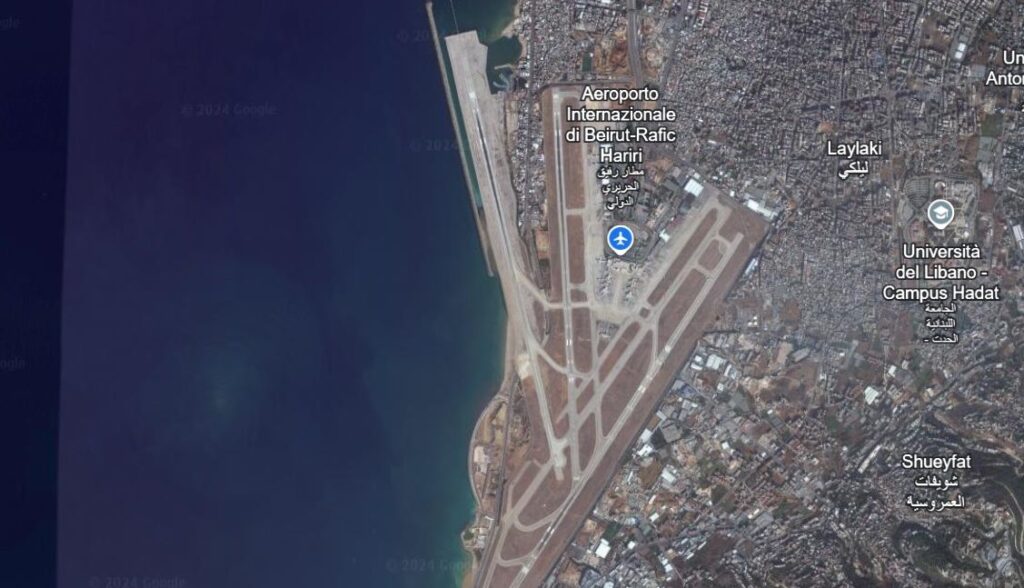

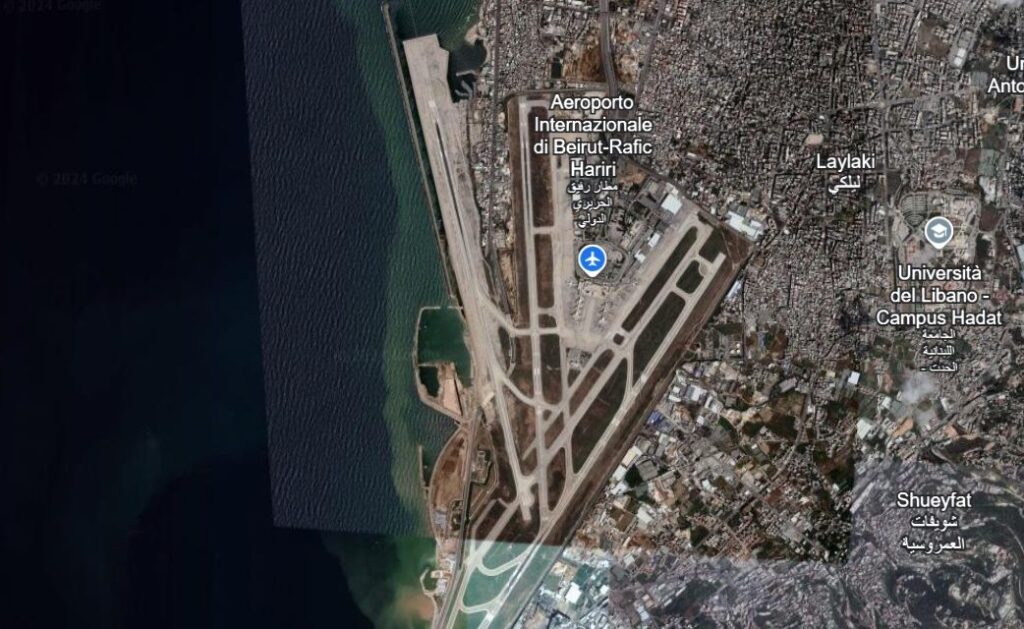

In the summer of 2006, for example, Dahieh’s debris was parked on the coast south of the international airport, in what years of mismanagement have turned into the Costa Brava rubbish dump. Since then, the coastline has become inaccessible, submerged by layers of rubbish and soil, and the surrounding marine environment uninhabitable, inevitably intoxicated. Satellite images make it possible to observe how rapidly the situation has deteriorated over the last decade, from 2015 – the year of the great waste crisis in the country – to the present days.

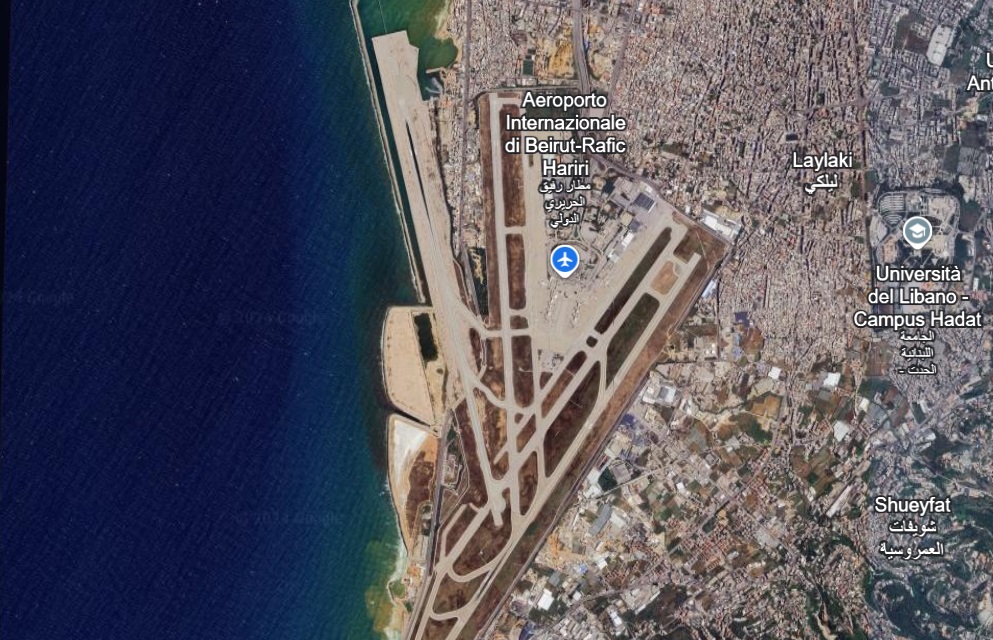

Satellite image of the southern coast of Beirut, at the Costa Brava landfill site, January 2015. Source: Google Earth

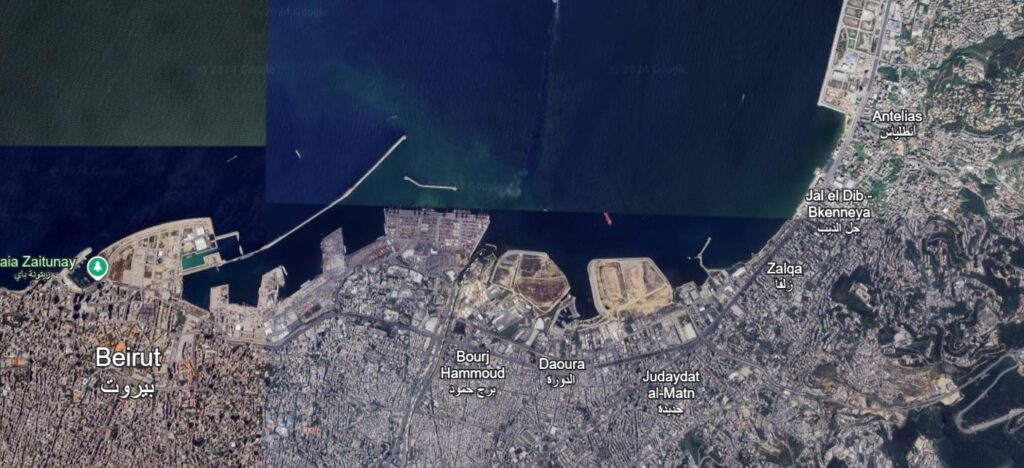

Satellite image of the southern coast of Beirut, at the Costa Brava landfill site, November 2016. Source: Google Earth

Satellite image of the southern coast of Beirut, at the Costa Brava landfill site, November 2018. Source: Google Earth

Satellite image of the southern coast of Beirut, at the Costa Brava landfill site, June 2024. Source: Google Earth

An hazardous fire

What the satellite images do not tell, however, beyond the greenish colour of the waters near the dumps, is the unliveability of these shores. In Bourj Hammoud, north of Beirut, another landfill – that of Jdeideh – poisons the air of the Armenian neighbourhood, whose leaders’ corruption – only mirroring a broader system – allowed it to be built without complying with safety regulations, and where a sudden fire, on September 12, brought the never-resolved Lebanese waste crisis back to the media’s attention. At least for a couple of days, before the pagers’ attack, on the 17th, pushed the country into another, unpredictable tragedy.

“Authorities claimed they equipped the landfill’s surface with geotextile membrane and even a leachate treatment station, which no one is probably monitoring,” comments Abi Chaker, answering my questions on the loud background of Israeli bombardments a couple of kilometres far from us, that keep on interrupting our conversation: yet determined not to let them transform the environment a secondary issue, not this time.

In order to be considered properly built, a sanitary landfill should have two layers of control, one for the leachate, the strongly polluted liquid that comes from the bottom of the waste, and one on top, devoted to the gas control, especially the methane. While in dumpsters, especially those built on the seashore, like that of Bourj Hammoud-Jdeideh, there’s no control, making the leachate going directly to the ground water, into the sea, polluting marine and aquatic life, and the fumes intoxicating the surrounding air, even in normal conditions. A fire like the one of September 12 could only furtherly increase the environmental risks, especially if PVC and hazardous waste are mixed with domestic organic material, which in Lebanon makes up to 70 percent of municipal waste. “The leachate comes mainly from the organic, and with the waste transportation system relying on compressor trucks, separating and composting becomes impossible,” Abi Chaker explains.

This has been the case since at least the Beirut port’s blast of August 4, 2020, when the nearby sorting facility of Qarantina was put completely out of action. “Four years later,” the engineer continues, “they’re taking waste as it is, without sorting it, and just dumping it in Jdeideh. This might give you an idea of how risky a fire on a site like this could be.”

To this day we don’t know what triggered it. It is enough, on a site with such a quantity of methane gas – which comes from the fermentation of organic without oxygen – to have a fragment of green glass touched by a sunray to ignite. “Simply, they’re dumping too much organic waste, that’s why the fire erupted. And because they put construction waste on top, at the bottom it ends up being no more oxygen, which means a huge volume of methane, an extremely inflammable material.”

At the same time, 10 million dollars were recently allocated by the World Bank to rehabilitate the Qarantina sorting facility: but if they insist on collecting and transporting the garbage in compactor trucks, making the separation of organic from solid waste impossible, that money is inevitably going to be wasted. A story that Lebanon seems to know very well. “Unsurprisingly, the file is in the hands of the CDR, the Council for Development and Reconstruction,” comments Abi Chaker. “And they will keep on making the exact same mistake, because that’s the only way they know how to make money out of the waste industry.”

The Burj Hammoud-Jdeideh landfill site a few days after the fire on September 12. Photo credits: Valeria Rando

A saga of mismanagement and corruption

The country has never had a comprehensive waste management system that covers its entire territory. Before the outbreak of the Civil War in 1975, the municipalities were in charge of the garbage collection: it was their responsibility to treat and collect waste. War, though, didn’t only mark the starting point of modern armed conflict, the deterioration of the state and the coalescence of militias in providing security – but it defined the modernisation of its waste collection industry.

Before it broke out, most of Beirut’s waste was dumped in Qarantina, back then a run-down neighbourhood near the city’s port. That, though, stopped in January 1976 – after a massacre conducted by right-wing Christian militias, the Phalangists, killed 1,500 of its majority Muslim inhabitants. It was only two years later, in 1978, that the capital’s municipality decided to dump most of its garbage into the sea. Both sections of Beirut, the eastern and the western, started dumping in a landfill called Normandy, located in what today is known as the Biel waterfront, in Downtown: and which was later discovered to have hosted a shipment of thousands of barrels of smuggled toxic waste from Italy, under the coordination of the Lebanese Forces, in 1987.

When Rafiq Hariri established Solidere, as a real estate developer, refused to keep a landfill in the middle of the city, on very expensive land. Nominated Prime Minister in 1992, Hariri took the decision to start dumping in Bourj Hammoud, with the small coastal dump growing exponentially, covering the Armenian neighbourhood’s sandy beaches and standing more than 40 metres high by the mid-1990s. With half of its volume submerged under the sea level, the dump reached, in 1994, five million cubic metres. The refuse was mixed with sand and war-time rubble from Downtown to create the foundation of what was supposed to become the capital’s finance centre: from war waste to dead bodies, every kind of scoria was thrown into the sea, causing a fatal, inevitable environmental disaster.

Still today, there is no knowledge of what waste actually lies buried in the dump site. The neighbourhood of Bourj Hammoud was clearly not deemed attractive enough for high-end real estate plans: when the war finished, part of the waste treatment process underwent privatisation, but plans to recycle the waste were implemented to only a very modest extent. The dump remained open until local protests shot the road to what had become a mountain, forcing authorities to close it in 1997.

After the closure of Bourj Hammoud’s dump, the waste from Beirut and its suburbs was sent to a newly opened landfill inland near the Chouf city of Naameh: the landscape of a valley owned by the Christian church surrounded by seven villages, soon filled with garbage, with the landscape dramatically changed. Supposed to stay for five years, it remained for triple the time. It was mainly a political deal: many politicians were making a lot of money out of Sukleen, the company that was monopolising Lebanon’s waste management back then.

In January 2015, the same scenario of 1997 Bourj Hammoud happened in Naameh. People started protesting, and the government asked for six months to solve the issue, which were clearly not enough. In July of the same year, the landfill was shut down totally, and as there was no alternative waste disposal plan, refuse sat, uncollected, for weeks in the sweltering heat in the streets of the capital, creating the 2015 rubbish crisis.

After the Naameh landfill hit its capacity, the government reclaimed over 280,000 square metres, equivalent to more than 39 football fields, along the waterfront of Beirut to establish the country’s largest and newest waste disposal site. Piling rubbish on the coast of one of the eastern Mediterranean’s most popular seafronts, it commissioned two private companies to build two new coastal landfills in 2016: one in Jdeideh, close to Bourj Hammoud, and one in the southern suburb of Costa Brava, next to the airport, on the same site that was ‘temporarily’ hosting the debris from the 2006 war.

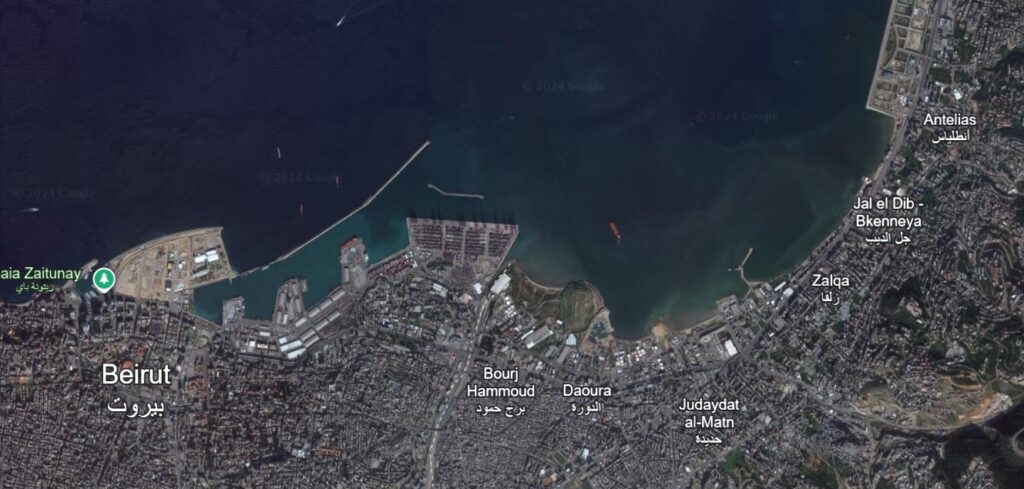

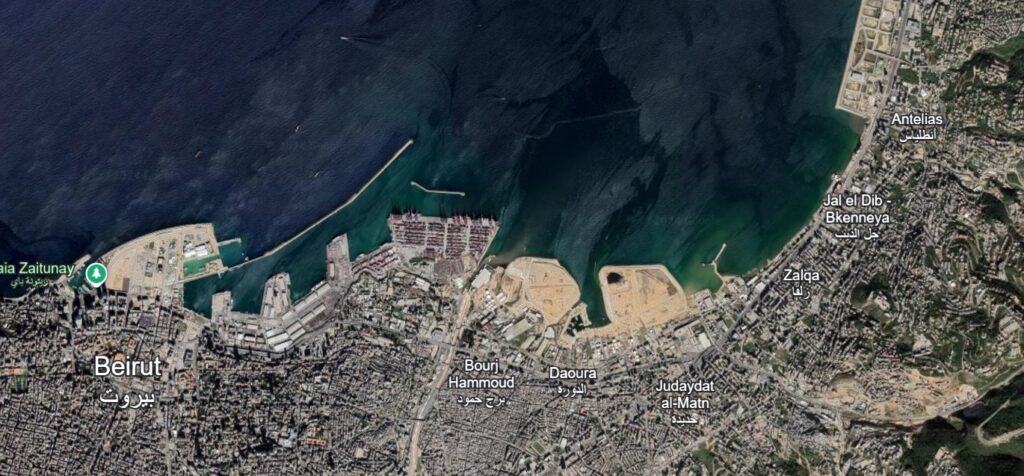

Satellite image of the northern coast of Beirut, at the Bourj Hammoud-Jdeideh landfill site, November 2015. Source: Google Earth

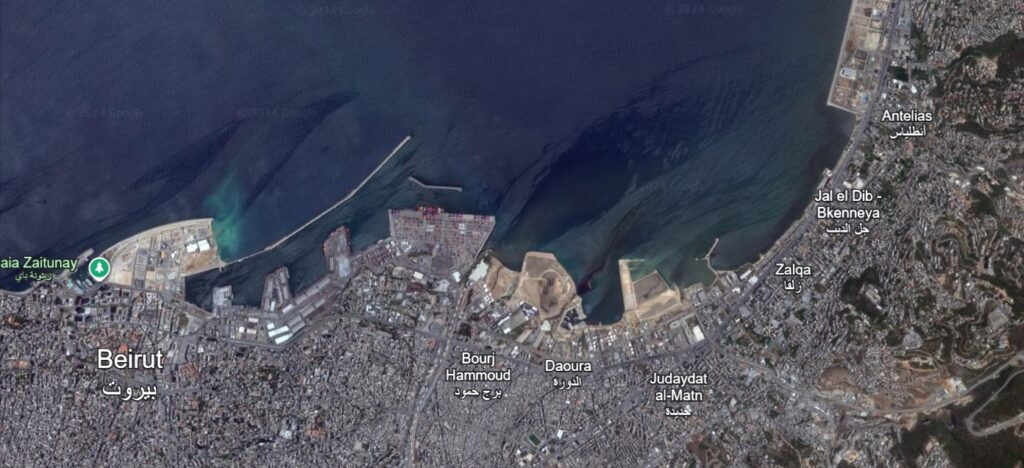

Satellite image of the northern coast of Beirut, at the Bourj Hammoud-Jdeideh landfill site, July 2017. Source: Google Earth

Satellite image of the northern coast of Beirut, at the Bourj Hammoud-Jdeideh landfill site, November 2018. Source: Google Earth

Satellite image of the northern coast of Beirut, at the Bourj Hammoud-Jdeideh landfill site, June 2024. Source: Google Earth

Thus, the newly-opened landfills in Bourj Hammoud-Jdeideh and Costa Brava, way bigger than the Normandy dump – created without the pretext of a civil war, the difficulty of movement of a civil war, the lack of control of a civil war – and which continued growing until the present days – unmask yet another sad face of Lebanon’s ungovernability: that of a corrupt system, playing at solving the manifold issue of waste management with its mere transportation. From one landfill, to a larger, more toxic, less manageable, other.

A sectarian issue

“The contract with Sukleen fell through because there was no place to take the garbage, and it remained on the streets for one year,” says Abi Chaker, who has been long pinpointing how waste management projects are monopolised by a group of few ‘fortunate’ ones, and explaining how, after more than twenty years of national failure in dealing with solid waste, this failure keeps happening over and over.

“The government ran a new tender because Sukleen was gone. But since the companies who were backed by the politicians did not win, they ended up cancelling the tender, and the crisis went on and on until September 2016, when a deal was reached. They split the contract for two companies – RAMCO and CityBlu – and since no one wanted the new landfills to be in their areas, the Christian part went back using the Bourj Hammoud’s site, and the Muslim part turned back to Costa Brava, the landfill for the 2006 war’s debris from Dahieh.”

So, waste has become sectarian, I comment. “It has always been like that,” he replies, “and Lebanon is no different than other parts of the world.”

Alternative vision

The affected municipalities were bribed for that. That of Jdeideh claimed 8 million dollars to establish the new landfill, while Choueifat should have been paid for the site of Costa Brava. Eight years have passed since 2016, and the landfills are still the same – filling up fast.

With the rubbish issue of the last war, and the memory of 2006 coming alive with images of villages liberated and found destroyed, one cannot avoid thinking about what will become of those mountains of garbage, from debris to organic material, from unexploded munitions to animals scories: and the risk of a new, permanent trash parking.

“I’m trying to push everyone to recycle the debris from this war. We have the quarries equipment that cannot be used. Instead, you’d need jackhammers to remove the valuable steel bars to resell, before crouching the concrete to make gravel.” From the gravel – to build roads, walkways, border stones. An incredibly urgent post-war issue: not at all secondary. “We could even apply this to the villages that need a new modern urban planning method, to rebuild in perspective.”

And just as on the one hand Israeli bombing razes entire neighbourhoods to the ground, and on the other hand waste mismanagement piles up toxic mountains along the coast – similarly, another contradiction emerges: while civil society fights to get rid of landfills, the government plans to bury Lebanon’s rubbish in the sea in order to build a highway over it. It’s the case of the Linord project, which aims at cleaning up the coastal area of the north side of Beirut between the rivers Nahr Beirut and Nahr Antelias, connecting Beirut to Dbayeh, burying – rather than converting – a big area of waste dumps under a district park.

Yet, Abi Chaker has another alternative in mind. “We envision each of the 26 administrative regions of Lebanon to be responsible for its own waste, having to build their own facilities for sorting and composting, and even their own landfills, if they want to use one. But I’ve been processing zero waste to the landfill since 2016.” “Of course,” he continues, “you would have to rely on the people as well. The beginning and most impactful step always starts from the local level, in the domestic separation between the organic and the recyclables. A daily-based collection system would substitute the garbage bins from the street. In this way, you would not have to depend on compactor trucks anymore.”

“Then, the existing landfills would be dismantled, and we would reclaim the coastal land of Jdeideh and all the other shores that our corrupted politicians have transformed into a toxic scape. What needs to be done is to only have a proper government in place, with proper accountability, and a decent judiciary system, capable of making things done, instead of only stealing.”

And he speaks, Ziad Abi Chaher, surrounded by objects of design made of recyclable plastic: the same they would usually dump or incinerate. “The applications are enormous,” and like a scientist in his laboratory, he points at the false ceiling above us made of cellulose fibre – the byproduct of Kleenex manufacturing, very inflammable when dumped in a landfill, but, from an engineer perspective, making the space so silent, for its acoustic property. “You see? Now, imagine doing it with 15 other components from your garbage bag. This stick, for example,” he stands up, picking one of what you would think as pieces of modern art from the shelf behind, “is made of this single-use plastic items, electronics’ package, espresso capsules, nuts bags, or the typical coffee cup used all over Lebanon. For a one-kilo stick, you need 153 supermarket bags. Things that if in landfills will stay there for a hundred years. But if you scratch your head and you think: this material will last a century, then you discover you can make things out of it.” And it’s clear that tomorrow, for a mistreated environment, hostage of Lebanon’s corruption, is already now.