“Hezbollah is a party that represents change,” he said. “Look how we went from a deprived community to having the upper hand in political decisions.”

The Hezbollah supporter preferred to remain anonymous when speaking about the two political parties representing the Shiites in Lebanon, the Amal Movement and Hezbollah. Though he didn’t have anything negative to say, “you never know how words get interpreted in the media and trigger consequences.”

Hezbollah supporters are not the only ones that reserve criticism they might harbour towards their parties. Criticism is quite rare among the Lebanese who still support the sectarian political factions that have been in power since the 1990s. According to the researchers and political analysts we spoke to, despite the vocal social anti-corruption movement that has emerged after October 17, 2019 and the recent wins the “thawra groups” have scored in university student councils elections and syndicates, many Lebanese still support the establishment parties, and many also remain heavily dependent on their networks for survival.

But in the summer of 2021, deep into the financial crisis that has seen the Lebanese pound plunge due to the scarcity of dollars, and extreme shortages of fuel, electricity and basic utilities, politicians preparing for the 2022 elections had to come up with strategies based on supporters’ needs to keep their constituencies loyal.

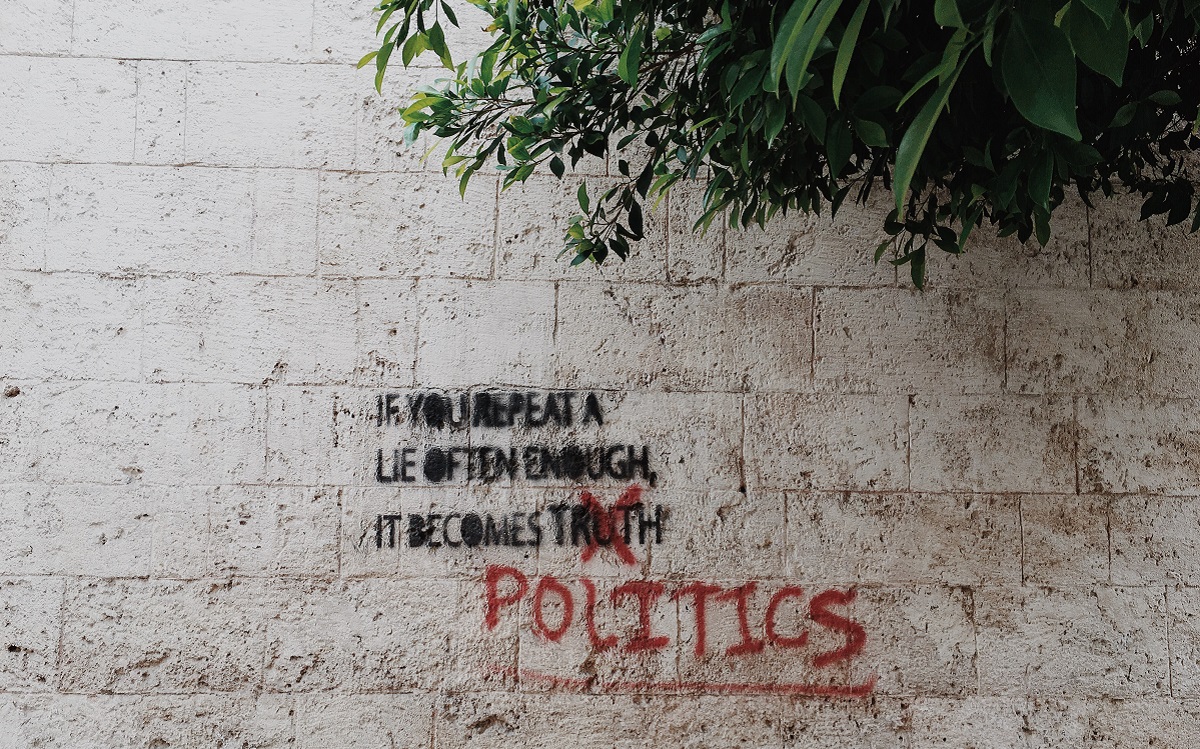

“They will use the same old dividing narratives of “us vs them” to divert people’s attention from the real issues. And these narratives work, people are in survival mode and will cling to their parties,” a political researcher who has been working on the matter and wished to remain anonymous told NOW.

Caretakers for their constituencies

After the port explosion on August 4, 2020, the Lebanese government put in place in January, 2020, resigned. In a televised address, Prime Minister Hassan Diab blamed his political foes, without naming them, for obstructing his efforts to fix Lebanon’s problems.

The country then fell into a rabbit hole. In a situation where the dollar exchange rate reached 20,000 LBP, parties focused on charity work to provide some basic needs for their loyal supporters and their families, ensuring COVID-19 vaccines and using their networks for priority in petrol stations.

“They have organized bases, this creates both trust and fear. Trust in the form of belonging and not betraying the group, which helped them win elections and assert the status quo and fear of the consequences in case they betray the group.”

Lebanese researcher (who wished to remain anonymous)

The researcher who spoke to NOW explained that standards of living have become so low that people were ready to accept any help they could get. Whereas previously, a simple food box of pasta, rice, sugar, salt and cheese did not mean much, nowadays people are ready to settle for even less. This gave parties more power and opportunities to potentially re-strengthen their base of loyal followers.

Hezbollah and the Amal Movement provided monthly food boxes, salaries and help with medicine and children’s education for their members. However, sources stressed that the “help” the Amal Movement provided was “much simpler” than what Hezbollah could provide. The difference in funding of the parties was obvious, supporters of both parties told NOW, on the condition of anonymity.

Supporters of the Christian parties, Lebanese Forces and Kataeb, told NOW that they volunteered for various non-governmental organizations to help people affected by the Beirut port explosion. The Kataeb party, for instance, worked with organizations “Make Your Mark” and “Kelna Aayle”. However, they said, they cannot distribute food and fuel.

“We can’t replace the government, so you won’t see us providing fuel and bread trucks,” Ralph Mrad, Kataeb party member and president of the students’ branch in the party, told NOW.

His reaction came to a statement made by the Iranian-backed Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah on August 15, who said the group would begin importing gasoline and diesel from Iran.

Supporters of Kataeb and LF said that, in contrast to Hezbollah’s funds from Iran, the two parties remained internally funded, relying on members helping each other to provide basic goods for people in need.

The survival of the sectarian narrative

Being sectarian in design, the political class has played on sectarian sentiment since the civil war. Amal Movement was the defendant of the “deprived Shiites”, while the Free Patriotic Movement’s minister Gebran Bassil painted himself as the protector of “Christian Rights” in his political statements.

“Sunni politics came to life based on the corpse of the Maronite Christians and robbed them of all their rights and gains, and we want to recover them completely,” he said in 2019.

Bassil has also stated in June 2021 that he trusted Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah to be “the protector of Christian rights.”

This caused a severe split in the Christian community between those against the Iran-backed alliance and its allies.

The Lebanese Forces stated that it refused to have an outside party protecting rights they have sacrificed lives for.

Tony Bader, Lebanese Forces party member and president of the students’ department, explained that they gained the trust of the people by being a party of resistance in its past battles.

The notion of sacrifice, blood, and martyrdom has been employed by all sectarian parties to gain traction and loyalty.

Researchers explained that their blood-fueled history made them trustworthy in the eyes of their followers and that violence-prone actions made the people fearful and loyal by force.

“They have organized popular bases, this creates both trust and fear. Trust in the form of belonging and not betraying the group, which helped them win elections and assert the status quo and fear of the consequences in case they betray the group,” the researcher stated.

“If you say that you are a group under a siege, like Hezbollah who stated last year that the United States was imposing a blockade, then resisting this blockade and being patient was a duty of yours and doing otherwise made you a traitor.”

Alain Alameddine, member of “Mouwatinoun wa Mouwatinat fi Dawla”

The sectarian political groups remained the only reliable source of protection and safety for large groups of the population. Especially, in light of current events, where physical safety has been threatened during daily occurrences and lives were lost in attempts to fill fuel. People want to feel safe, and their comfort zone remains with their sect, tribe, and political group. Non-sectarian factions cannot provide the same protection.

“From a realistic perspective, people just want to eat and live so it does not matter who that side is anymore.”

Thus, the established political groups are likely to retain their role as providers, as long as the situation worsens.

The “Us versus Them” narrative

Clientelism, a symptom of the sectarian system, divides society into two classes – those with benefits and those without. Experts explained that the stronger your political ties, the higher were your chances at getting jobs, especially in the public sector and the security forces, and accessing resources such as fuel and electricity.

But these are not the only divisions.

Members of new political movements born from the October 2019 protests say that the “Us vs Them” narrative helps distract attention from the real issues at hand – corruption and impunity.

For example, politicians in Christian, Druze and Sunni parties claim Iran as their opponent and Western countries as friends. On the other hand, Hezbollah and its allies claim Israel as an opponent, look at Western states, especially the US, as friends of Israel and accuse them of imposing a blockade on Lebanon, as the fuel crisis in the country deepens.

Alain Alameddine, 35, member of the political party “Mouwatinoun wa Mouwatinat fi Dawla” (Citizens in a State), explained that this divisive narrative was the quickest way to silence people by making them think they are under siege.

“If you say that you are a group under a siege, like Hezbollah who stated last year that the United States was imposing a blockade, then resisting this blockade and being patient was a duty of yours and doing otherwise made you a traitor,” Alameddine said.

“In my opinion, once a new government is formed by Mikati, they will be able to provide some pain killers to the body of the country. They will convince you they’re conducting reforms, and acting differently, but in reality, little will change.”

Mohanad Hage Ali, fellow at Carnegie Middle East Center

This perception of constant threat strengthens the loyalty people have towards their sectarian group. Accepting their reality became a prideful act.

Alameddine explained that the authoritarian policies Hezbollah applied isolated the group and the Shiite community from society, which increased the sectarian division in Lebanese society.

“I once heard a protestor that said that the Shiites can take the areas they want and leave the rest of the country for the rest of us. You also have people who were happy that Sunnis and Druze would stand against the Shiites.”

Alameddine also said that the Lebanese Forces also have been using a populist discourse and have become the most vocal against Iranian occupation – although the current was already present in civil society. This also creates the perception of a country and community under siege.

“If you say you are under Iranian occupation then this is very dangerous because you’re basically saying that violence was needed [to fight this occupation]. You also lose sight that Hezbollah members were Lebanese and not Iranians and we lose sight of the bigger issue, the sectarian system.”

” If we remove Hezbollah for example, another similar faction will spring up because the issue is deeply rooted in our system,” Alameddine added.

Providing the bare minimum

Without fuel, cooking gas, electricity, and food, the bar is set low. The political class could easily regain some of the popularity it lost, as the people long for a saviour.

Prime Minister-designate Najib Mikati promised to name a new cabinet as soon as possible and has been negotiating with President Michel Aoun a lineup that is satisfactory for everyone, including an international community that wants sectarian factions to divide portfolios and name a technocratic government. Hopes are high, but expectations are low. Sectarian political factions have been negotiating on who gets which portfolio, but Mikati admitted on August 17 that the conversation has been less about plans for reforms and policies to recover from the economic crisis, and were focused on who gets what. But he said he has the entire cabinet policy plan in his head.

In Beirut, noone believes in illusions anymore: Mikati’s cabinet, if formed, is here to buy time for the sectarian set up of the political establishment.

In the meantime, political parties work on their strategies to keep their constituencies loyal and reinforce their allegiance ahead in the 2022 elections, if they actually happen.

Bader stated that the Lebanese Forces were training their young members into understanding their history, knowing their fight, organizing their behavior in the diverse society they lived in, and fully comprehending the ideologies they were subscribing to.

Kataeb members said they would continue to provide aid through civil society organizations.

Hezbollah promised Iranian fuel.

Amal Movement, Future Movement and others said they provided aid to the needy and did charitable work.

All these efforts may be enough, Mohanad Hage Ali, fellow at Carnegie Middle East Center explained.

“People are in such a state, with hunger and total blackout knocking on their doors, that any improvement would go a long way,” he pointed out.

He said the country is headed towards a new phase where the political groups will switch from the defense to the offense mode, if the government is formed.

“In my opinion, once a new government is formed by Mikati, they will be able to provide some pain killers to the body of the country. They will convince you they’re conducting reforms, and acting differently, but in reality, little will change.”

One trick the government could resort to is to lower the exchange rate, which would throw a lifeline to public institutions. By lowering the USD exchange rate from 20 thousand LL to 15 or even potentially ten thousand, they would temporarily increase the army’s salary from $100 a month to $150, he explained.

Hage Ali added that politicians in power most likely are planning to postpone the 2022 elections to allow enough time to regain some of their popularity. Given the current low bar, a higher exchange rate, improved access to fuel, and reconstructing the Beirut port would go a long way in appeasing public anger.

After a series of protests in 2019 and increased poverty, it seems that the ruling class could come out of this victorious. But what about the long-term and who was there to stop them?

Hage Ali said that there are no real political adversaries that the veteran politicians who play on sectarian lines and economic needs would take seriously. This allowed them to behave however they wanted.

As a member of a newly established secular political faction, Alameddine, however, believes that the civil society should have a bigger role to play in politics at this time and that the message of political coexistence should be clearer.

“As political groups, we aim to lead this transitory phase and to gain political legitimacy so that we could implement changes to the system. We want to work against them politically, that’s it. We don’t wish to kill them. We understand they exist and we want to exist with them.”

The goal, he says, is to have political disagreements, not tribal disagreements.

For Hage Ali, however, these dreams and aspirations require more action.

“This is a real power game, either you put the blood on the table and fight or you don’t. You can’t be on zoom for ten hours discussing how to take down the establishment. This takes you nowhere.”

While Alameddine stated that the civil society has been working on a campaign that would soon be announced regarding practical actions for the future, Hage Ali believes that political parties hold a strong sectarian narrative that no one can currently topple, unless they were willing to put the time and effort into creating a new reality.

But according to the anonymous researcher mentioned earlier, the politicians in power seem to believe that the people are still capable of taking more hits until they are desperate enough to accept the scraps. With less money and more crises, politicians still demand more of their followers: more support, more patience, more loyalty and more resilience.

“They [the politicians] never apologize but they keep saying we are under threat and we need your support. They escape responsibility and put the blame on someone else, then they can ask their supporters to back them up, in order to keep themselves and the community safe.”

Dana Hourany is a multimedia journalist with @NOW_leb. She is on Instagram @danahourany.