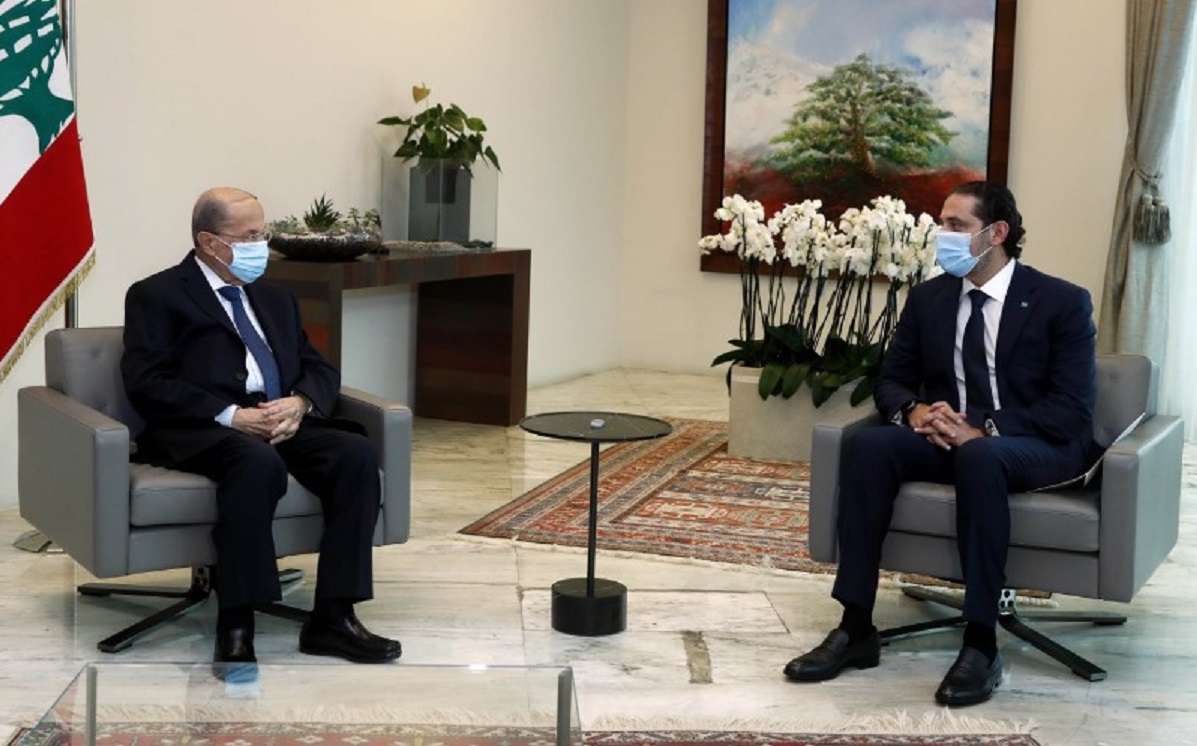

Lebanese Prime Minister-designate Saad Hariri stood in front of the press, as he had stood many a time before, after concluding yet another round of government formation consultation with President Michel Aoun.

It was March 22 when the two politicians met, and much-awaited government meant to pick up the pieces of the financial crisis, several Coronavirus lockdowns and the August 4 explosion that destroyed large areas of Beirut was not going to be.

Hariri has spent over six months since he was appointed going on diplomatic tours meeting with the presidents of Turkey, Egypt, France, Saudi Arabia, and, most, recently, Pope Francis at the Vatican.

The ambassadors of France and the United States sat on many occasions with both Aoun and Hariri to try to mediate the deadlock.

To no avail.

Walid Bukhari, the Saudi ambassador, stated that it was important for everyone to put the “higher national interest first” after he met with Aoun on March 23.

Macron, fed up with the lack of results nearly a year after he launched the French initiative, said that the “time of the test of responsibility is coming to an end” and that there needs to be a “change” in approach.

US ambassador Dorothy Shea called on the political leaders to “put aside their partisan differences and work together” in order to form a government and put an end to the crises that Lebanon is facing.

Hossam Zaki, the assistant secretary-general of the Arab League, stated that the Arab League is willing to do “whatever it takes” to help Hariri form a government that complies to the requirements set forth in the French initiative.

Foreign leaders have helped many times in the past by pushing for a political consensus in Lebanon when local politicians seemed entrenched in insurmountable ambitions to get the blocking third in the cabinet. Most of the time, the Lebanese political crises were solved abroad.

But not this time.

Hariri is not the first PM-designate who has had trouble forming a government in Beirut. Former Prime Minister Tammam Salam holds the record: it took him 329 days in 2013-2014 to get the Lebanese factions to reach a consensus and come up with a unanimously accepted list of ministers.

But analysts who keep a close eye on Lebanese affairs say that Hariri may have a much more difficult job putting together the cabinet in 2021 than he or any of his predecessors ever had in the past.

The country is facing an unprecedented state of affairs: an economic crisis like none before, street protests demanding the demise of the old sectarian system, growing secular youth movements winning elections in universities, and a devastating Beirut blast that has seen the Lebanese trust in the political establishment dive to unforeseen depths.

“In the old days, you could really [recycle] any old cabinet and it didn’t matter,” Paul Salem, president of the Middle East Institute, told NOW.

“Life would go on; the economy would go on no matter who was minister of finance or minister of industry or minister of energy. The economy was kicking along and people were going about their lives. Now that is no longer workable.”

The trouble starts with Taif

The endless negotiations are partially due to the Lebanese power-sharing system which requires all sectarian factions to have representation in the government. Other countries that use this model, such as Belgium and Northern Ireland, have also faced similar struggles with forming a government. In Belgium, for instance, it nearly took a year and a half to form a government in 2018-2020.

Since the Taif Agreement that ended the Lebanese Civil War in 1990, there has hardly been any occasion when Lebanese politicians were in any hurry to form a new cabinet. After the Doha Agreement that put an end to a series of street armed clashes between Hezbollah and Future Movement supporters in Beirut in 2008, it became even more difficult to reach political consensus.

Ziyad Baroud, who served as the minister of interior for both Fouad Siniora and Saad Hariri from 2008 until his resignation in 2011, says a major issue that causes the delays with government formation is the lack of provisions in any of the agreements giving the president a set deadline to call for parliamentary consultations and the prime minister-designate a time-frame to actually form the government.

“This is a problem because the prime minister-designate could put this designation in his pocket and wait an eternity,” former Interior Minister Ziyad Baroud told NOW.

Another problem is in the process of choosing a prime minister.

“[…] The president could not just name any Sunni prime minister,” Salem said. “The president had to legally consult with parliament and the deputies in parliament would tell the president who they would like to see as prime minister.”

Like the cabinet formation talks, there is no set deadline for the parliamentary consultations, so the process can drag on until a candidate has majority support in parliament. Salem explained that prior to the official consultations, there will be backchanneling between the different blocs to see who they can agree on, but even this can take a long time due to infighting amongst parties.

Since the caretaker government is restricted to managing their current tasks and cannot create new policies, during times of crisis, such as the economic collapse that the country is now facing, any delays in forming a new government can spell disaster.

Another major change was an unofficial agreement between the various poles of power in the Lebanese system. As part of Lebanon’s power-sharing after the 1943 National Pact between President Bechara al Khoury and Prime Minister Riadh el Solh, the president was always a Maronite Christian and the PM a Sunni Muslim, with Shiite Muslims having no official positions within the executive.

During the Taif Agreement, it was unofficially granted that the Shiite parties would always maintain the portfolio of the ministry of finance so that they can have veto power in any decree or any law that needs the executive power to approve, political analyst Mouafac Harb told NOW.

“If you take the ministry of finance away from the Shiites, then the Shiites would not have any power or any veto power over any proposed decree or law.”

Since this is the only position that can give the Shiites the executive veto power, the two Shiite parties, Hezbollah and the Amal Movement, have refused to give up the ministry even if it means bringing government formation to a complete stop.

After then-PM Hassan Diab resigned on August 10, Lebanon’s Ambassador to Germany, Mustapha Adib, was chosen to form a new government on August 31 so that Lebanon could receive aid from France, a prerequisite of French President Emmanuel Macron’s relief package. However, Adib tried to hand over the finance ministry to a non-Shiite, a move that led to the Shiite duo bringing negotiations to a standstill. Eventually, on Sept. 26, Adib announced that he would step down as PM-designate since no agreements could be reached.

Parliament deals

The formation of a new cabinet is dependent on parliament’s approval, making it imperative that the PM-designate has all the major blocs represented and satisfied with the list of ministers.

Thus, parties with a large number of seats in parliament have been able to install party loyalists into ministries regardless of their qualifications, just because the PM needed the votes, Harb explains.

Parliamentary blocs would also try to achieve a “blocking third” in the cabinet, making sure no policy they don’t agree with makes it out of the cabinet meetings. According to Lebanon’s constitution, if a third plus one members of a government resign from their posts, then the entire government falls.

“That blocking third gives unfair or oversized leverage for any third over the entire government,” Salem explained. “And that is something that the prime minister has found unfair because effectively the major decision-making in his government is controlled by a minority.”

Saad Hariri himself went through it in 2011: his cabinet fell after the head of the Free Patriotic Movement Gebran Bassil announced that all 10 members of the opposition parties were resigning their seats. The move came after months of bickering between the PM and Hezbollah over funding the Special Tribunal for Lebanon after four members of the group were indicted by the international court in the case of Rafik Hariri’s assassination.

The regional playground

Until the Cedar Revolution in 2005, Damascus largely controlled the government in Lebanon, including its formation.

“There was a boss basically,” Salem said. “Whenever Syria said ‘Come on guys you’ve got to form a government,’ then a government would be formed.”

The Syrian withdrawal, however, left room for more foreign interference and competition: Syria remained in control of some factions and politicians in Beirut, while other regional players, such as Iran and Saudi Arabia, also came into the picture. Moreover, pro-Western factions would also seek solutions in Western chanceries, especially in Paris and Washington. The result was, according to Harb, that the decision-making process became dependent on foreign intervention.

“And this is what leads to a gridlock like what we are witnessing right now,” he pointed out.

Since the start of the Syrian Civil War in 2011, much of the focus in the region has been on Lebanon’s neighbor and has seen Lebanon increasingly neglected by regional and international powers.

According to Salem, the US, under the Obama administration, has increasingly tried to distance itself from conflicts in the region after the failures in Iraq and Afghanistan, only getting involved when the Islamic State emerged as a global threat.

The Gulf countries had hoped that Assad was going to be removed from power during the initial years of the war, but after Russia got involved in the conflict in 2015 and the Islamic State started gaining territory, they quickly realized that this would be unlikely.

“They also figured that if they weren’t going to be able to do much in Syria, then they definitely wouldn’t be able to do much in Lebanon and that Iran was winning,” Salem explained. “They kind of gave up on Lebanon as being hopeless.”

Unprepared in the face of disaster

Since 2019, Lebanon has been facing an economic and financial crisis that has seen the value of the national currency in freefall. Then, after the August 4 port explosion, the country’s political crisis deepened.

Since Lebanon was in the middle of an economic crisis, the government could not afford the costs of reconstructing the capital and now has to rely on foreign assistance.

However, due to the political class’s long history of corruption, France, who was offering assistance, demanded that a new government of experts be formed to replace Diab’s caretaker government following his resignation before any money was released.

Salem argues that because of the current economic situation, Hariri can no longer recycle any old cabinets to appease the sectarian factions because such a government would be rejected by both the Lebanese people as well as the international community who would refuse to provide financial assistance.

In addition, the country is facing elections in 2022. The new parliament would have to elect a new president, and agreeing on a name for the post has proved to take even longer than forming a cabinet. Before Michel Aoun was elected in 2016, the country had been paralyzed by a 29-month deadlock over the presidential seat.

“In case the Lebanese fail to elect a new president, this cabinet would be in charge of the country,” Harb said. “That’s why everyone is trying to make sure that they are represented and represented the way that they want to be in terms of size and influence.”

Technocrats: a teaspoon of fairy dust

Newly emerged Lebanese political movements after the large protests in the fall of 2019 as well as the international community have been demanding a technocratic government made up of ministers that do not have any political allegiances to the sectarian factions.

“We are asking the political elite to form a government that would lead to their own demise and they are not going to do that,” publicist Mouafac Harb told NOW.

The establishment is willing to compromise very little. Politicians will only come up with new names, whose affiliation is not yet known or who are not directly linked to a particular party. However, they would still be close to political factions and would remain loyal to the parties that brought them the cabinet seat.

“This leads to the same result,” Baroud also explained. “For me, it is not only about technocrats, it’s about independent technocrats. If you have technocrats who are not independent it’s nonsense. It’s useless.”

The upcoming elections in 2022 could force change to the traditional government formation. Baroud says that the October 17 uprising was a game-changer and that if more independents are elected to parliament it would change the political calculus the sectarian factions have been operating with for decades.

“I’m not saying that the 128 seats of the parliament will be taken by new political groups or revolution [groups] or independent people,” he said. “I believe that all traditional political parties will all have their own seats as well.” But things are likely to change in many regions, he added.

For months, both Hariri and Aoun have been playing the blame game for the current gridlock in consultations. Aoun alleges that Hariri has not given him any names while Hariri says that Aoun and his party refuse the proposed lists in order to obtain a blocking third. The blocs are trying to get their blocking third in the government, but Hariri insists that he will not allow any bloc to hold this veto power.

With the declining situation in the country, Baroud expressed disbelief and anger at how the political elite continues to focus on trying to get more or better seats in the cabinet.

“We’re in a time when the situation on the ground does not allow these sorts of games,” Baroud exclaimed. “People are starving. In a way, Covid-19, the banks, the finance, if you put all of this on the table, you end up understanding that the cabinet should have been formed yesterday and not tomorrow.”

Nicholas Frakes is a multimedia journalist with @NOW_leb. He tweets @nicfrakesjourno.