His small studio in Ashrafieh was destroyed and many of his paintings were lost due to the August 4 blast, but when asked about Beirut, Syrian artist Sami AlKour replied: “I still love it despite it all”.

For the 30-year-old artist, leaving Syria in 2018 to start over in Beirut was a dream come true. The city represented to him everything he lacked back in his country.

“When I first arrived, Beirut was lively and full of joyful people. Everything in it was inspiring, especially the sea,” he said.

But then he witnessed his neighbor’s death on August 4, 2020, when the port blast happened.

“I didn’t witness this much horror even back home in Syria,” AlKour said.

After the explosion that killed 218 people and destroyed swathes of the capital, including various districts connected to the arts, the art scene in Lebanon lost its spark. Many galleries and studios were damaged or closed completely. But in 2021 some young local artists tried to regain some of the lost hope. Group exhibitions dealing with healing collective trauma have started to open for the public, as artists are putting out their own internal processes of grief and loss.

Sami AlKour: “Just like talking to a therapist”

For AlKour, art is now a way to deal with grief and finding “hope in the darkness”.

AlKour’s work is part of “Visions of Today“, a group exhibition in Gallery Janine Rubeiz that opened in July and displayed pieces by the participating artists that shared their vision on how they saw Lebanon moving forward.

“I use dark colors in contrast to lighter ones as a way to express the hope that is always found in the darkness,” AlKour said.

He also painted on some of his small canvases that were torn due to the blast to preserve the impact. “I wanted to safekeep these canvases because I felt like they were the soul of the explosion so I poured everything in me, all the misery and the sadness that we’ve lived onto these paintings,” the artist explained.

For AlKour, his pieces were a way to deal with the country’s harsh reality and all that he had endured. By producing art that stemmed out of the direct trauma, he felt like he could finally overcome the pain he had dormant in his psyche. It was a therapeutic process needed when traditional therapy has become unaffordable and inaccessible to many due to the financial crisis.

“Just like talking to a therapist, I feel like my canvases get these feelings out of me without using words and without them I wouldn’t be able to continue,” he said.

AlKour also considers the type of art that stemmed out of the port explosion and the Lebanese crisis in general, a way to safeguard and archive the historical events currently occurring.

Sarkis Sislian: “Confused, dark, all over the place”

Sarkis Sislian, a 29-year-old Armenian-Lebanese artist was in the comfort of his home in Mar Mikhael when the explosion occurred. He had been studying visual arts in one of the most prestigious art schools in the city when the economic crisis hit. He lost his bartender job, which had helped him stay in school. Art was his only escape.

“I suddenly found myself drowning in a sea of problems, none of which I was prepared for. I only knew how to produce art,” he said.

“My drawings and paintings are exactly how I feel, confused, dark, and all over the place,” he stated.

Sislian and several emerging artists took part in a group exhibition titled “I don’t want to talk, but…”. It opened on August 20 and dealt with the teenage perspective on the loss of words in light of the country’s situation. It was Sislian’s first exhibition.

“Participating in these group exhibitions makes me feel that I’m less alone and isolated in whatever I produce and whatever I feel,” he added.

Sislian is unsure whether he would make any money out of small exhibitions, but right now, reviving the art scene was more of a priority.

Danielle Krikorian: “All I have left”

Danielle Krikorian, 25, studied art history and studio art at the American University Beirut and continued her Master’s degree in Art History at the University College London.

Like AlKour, she said she also believed in using art to archive the events currently happening in Lebanon, and was specifically attached to the concept of “memory” and the way art represented civilizations and cultures throughout history.

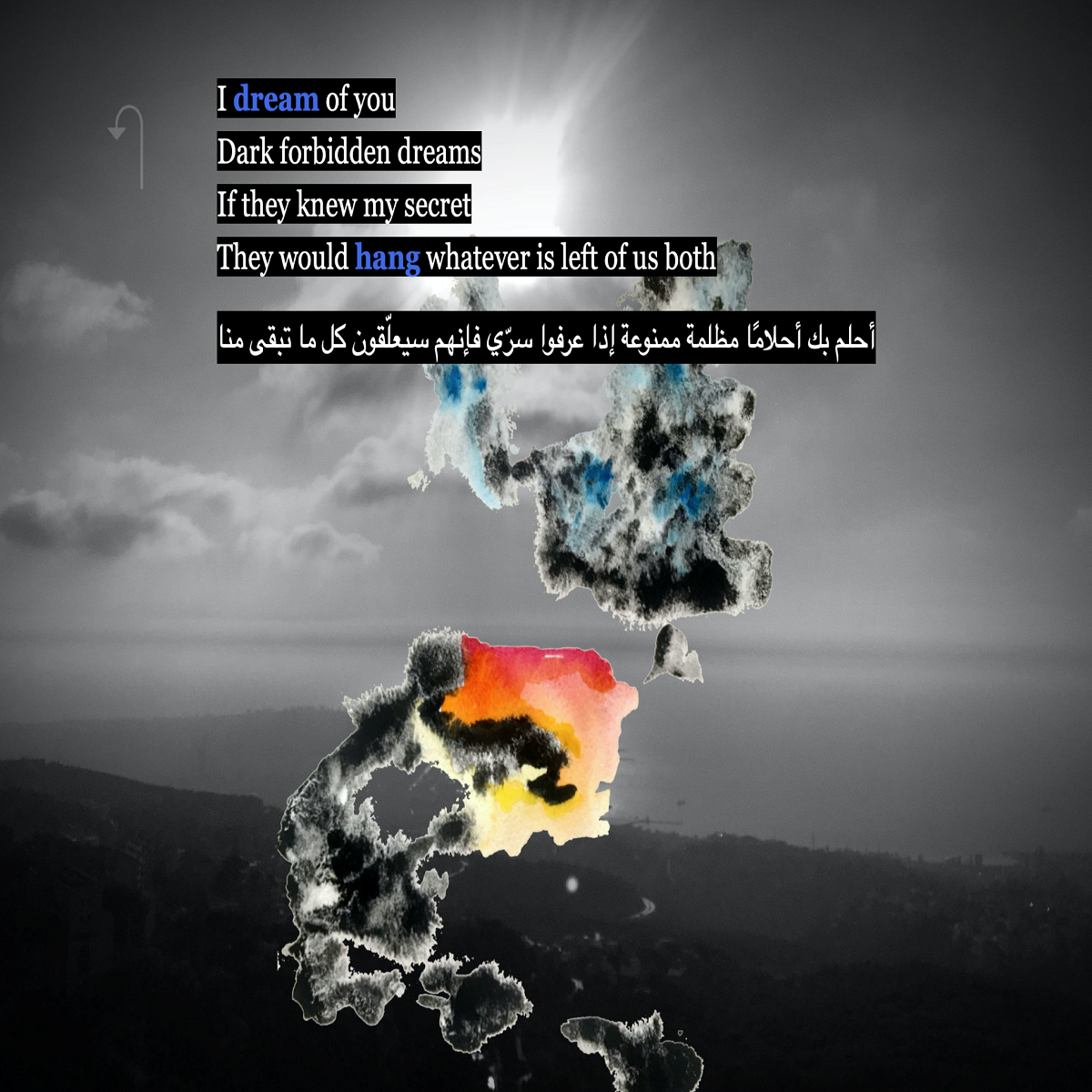

Krikorian has two exhibitions at P21 gallery London, a London-based charitable trust promoting contemporary Arab art and culture. She exhibited “Forbidden Dream”, an interactive landscape poem and “Soundbites From the Protest”, a mixture of different field recordings from the August 4, 2021 port blast memorial protest.

“Forbidden Dream” is a digital poem that the audiences watched online, skipped through multiple pages that displayed different landscapes of Lebanon as well as the artist’s paintings of her relationship with the homeland.

The second piece, “Soundbites From the Protest”, was about anger.

“I had a really hard time making the soundbite piece because it’s very personal. It reflects my outlook on what’s going on with the country. When you hear the voices of other people and you realize how much the ruling class has taken from us… for me, this is all that I have left,” Krikorian explained.

For her, culture and art were the only things left in this country. They helped her express her love-hate relationship with the homeland.

Krikorian considered art as a healing medium in certain cases, but she stressed on its function for historical preservation.

For Krikorian, it was more about preserving the means of expression of the collective during a specific time period using art, literature, and pop culture.

Even though she chose to come back to Lebanon when covid hit, living and working amidst the economic crisis was not an easy decision to make.

When home doesn’t feel like home

AlKour called Beirut his home for the last four years, but after the blast, he and many others were stuck in the dilemma of whether they should leave or stay.

“Art helps me deal with the issue of immigration due to the constant confusion of whether it was worth staying here or it was the time to go,” he explained.

He expressed his confusion through paintings inspired by his favorite Lebanese feature, the sea. He used the example of the fish’s migration to signify the bulk of people leaving the country.

“People always encourage me to leave but there is something that keeps me here, I keep holding on to it, and painting these feelings empties my mind from all these thoughts,” AlKour stated.

Krikorian realized that both staying or leaving meant sacrificing a lot. She did not wish to leave, but felt as if the political class were pushing the people to do so.

“There’s a lot of heartbreak and lots of nostalgia for life before everything spiraled down. There’s also the longing for a better country. So many bad things were done to us by the regime but there’s something about the land and the people that keeps you attached,” she explained.

Krikorian says she will stay in Lebanon indefinitely. Though she feels uncertain about her future, a deep connection and love towards her country keeps her here.

“For better or for worse this is still home and I don’t think we should give excuses to why we choose to stay,” she said.

Dana Hourany is a multimedia journalist with @NOW_leb. She is on Instagram @danahourany.