The coming months may be some of the most important in Lebanon’s modern history. Besides the fact that the Lebanese elections are less than a month away, the people of France are also heading to the ballot box to choose their country’s leader, which will consequently have a massive impact on Lebanon’s future.

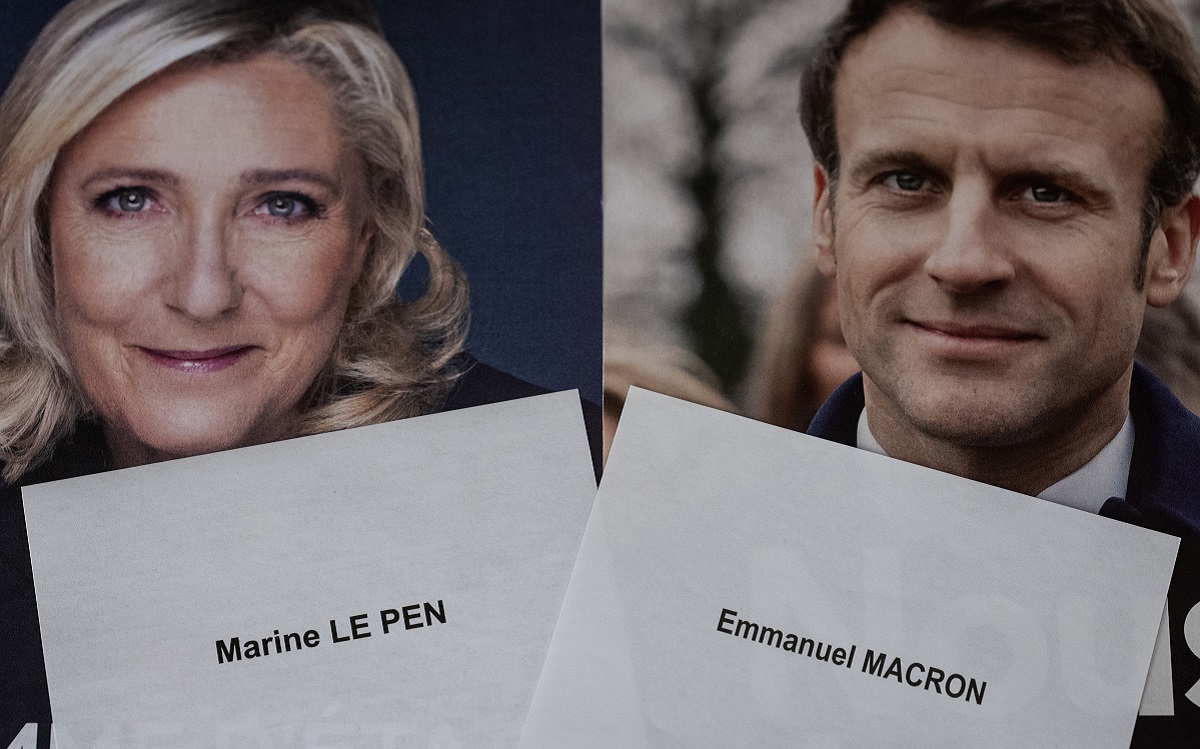

On April 10, the first round of French elections took place, with Emmanuel Macron, the current center-right President of France, and Marine Le Pen, his far-right challenger, making it to the second round, which will be held on April 24.

Macron has been the most popular candidate for the Lebanese who have French citizenship, and this has been reflected in their voting habits. Macron is likely the more pragmatic choice, but there are some elements of Lebanese society that view Le Pen as the better option regarding Lebanon.

Each candidate offers a very different vision for France’s future, with Macron offering a continuation of the last five years of his rule and Le Pen running on a nativist and eurosceptic platform.

Both candidates also have starkly different approaches to foreign policy, and this has serious implications for Lebanon. Macron’s desire to assert French interests on the world stage lies in sharp contrast to Le Pen’s skepticism of the international order.

Regarding Lebanon, analysts say a Le Pen victory could have serious consequences for the crisis-stricken country, while another term for Macron would likely mean a continuation of his foreign policy goals of the last five years.

France’s role in Lebanon and a Macron victory

Since taking office in 2017, Macron has sought to increase France’s influence in the Francophone world as well as the international stage. He has focused on asserting France as an integral part of the international community while pursuing French interests abroad, making Lebanon a linchpin in his foreign policy goals.

After 2019, in which Lebanon fell into a number of crises, including economic collapse and the 2020 Beirut port blast, Macron has made clear that France will play a strong role in Lebanese politics.

“France under Macron did take many initiatives to support and help the Lebanese,” Fadia Kiwan, a professor of political science at Saint Joseph University of Beirut, told NOW. “They tried to help the Lebanese through civil society organizations, because they said they don’t trust the state.”

Macron has been vocally critical of Lebanon’s corrupt and dysfunctional political class, but he has still worked with it to safeguard French interests in the country.

Kiwan pointed out that many Lebanese had high hopes for France’s role in the country, believing that Macron might support the opposition in its quest to unseat Lebanon’s well-established sectarian parties. However, they quickly became disappointed and disillusioned, as many now think that Paris has not put enough pressure on Lebanon’s politicians to enact meaningful reforms.

“We are more realistic today that no one will help us,” she said.

Kiwan noted that Macron had also made inroads to Hezbollah, and he sees Lebanon as a tool in dealing with Iran.

Macron may believe that France’s best option is to act as a mediator, dealing with all sides in the divided country and maintain an equal distance between domestic and regional factions.

Ayman Mhanna, the Executive Director of the Beirut-based Samir Kassir Foundation, told NOW that “when it comes to Macron… We cannot expect a lot of change to the situation right now.”

He went on to explain that though Macron had made strong statements regarding reforms, he is, in reality, more interested in stability. Overall, Macron simply does not want to shake up Lebanon’s political scene and risk further instability or conflict.

“He has engaged with the current political class, and will most probably continue to do so moving forward,” Mhanna said.

He was quick to point out, however, that Macron was not as cynical as some people have made him out to be. He has, of course, helped prop up the political class, but there is more nuance to his position than simply maintaining Lebanon’s corrupt elite.

Since drives to implement reforms have so far failed, Macron has helped the political class by using its members as interlocutors and, consequently, giving them legitimacy. However, Macron’s actions have indicated that he does expect to see at least some changes.

“When it comes to money, Macron has been quite strong on actually not giving a penny unless reforms are enacted, and I think this will continue,” Mhanna told NOW.

With the war in Ukraine and over two years of the pandemic, France does not have the funds to just inject resources into the Lebanese state without reassurances that the political scene will improve.

Outside of finances, Macron has also focused on security, cooperating with the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) and sharing intelligence, which Mhanna said would likely continue.

Eastern Mediterranean gas and a nuclear deal

France has a variety of interests in Lebanon and the broader region, including cultural, historical, and financial ties, but both Kiwan and Mhanna agreed that the two most important issues on France’s agenda are natural gas in the Eastern Mediterranean and dealing with Iran.

Indeed, Macron sees Lebanon as a linchpin in his regional and international strategy. France has lost much influence in Africa and the Middle East in recent years as competition with Russia and China has expanded while the region’s big powers, such as Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Turkey, have undertaken more proactive foreign policies.

Mhanna explained that the deployment of Russian security contractors, namely the Wagner Group, to multiple African countries, such as Mali and the Central African Republic, along with the wave of military coups that have swept across West Africa has infringed upon France’s traditional spheres of influence.

In this context, Macron can use Lebanon as a launchpad into regional politics and to solidify France’s sphere of influence.

“Lebanon remains a place where [the French] have a significant level of influence that allows them to actually engage with other powers,” Mhanna told NOW.

Having a strong foothold in Lebanon allows France to explore the possibility of natural gas reserves in the Eastern Mediterranean and pursue a diplomatic strategy toward Iran.

“Being present [in Lebanon] allows them to engage directly with all these issues, while at the same time having a very important connection with the issue of gas in the Eastern Mediterranean… But gas remains an ‘if,’” he explained.

The nature of the Eastern Mediterranean’s gas is still unclear, and would require further exploration and investment, but given Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent hike in oil and gas prices, France has a strong interest in looking into the possibility of substantial gas reserves.

Lebanon remains a place where [the French] have a significant level of influence that allows them to actually engage with other powers.

Such exploration would require cooperation and strong relations with the countries of the Eastern Mediterranean, and a strong position in Lebanon would be advantageous in securing agreements throughout the area.

Regarding Iran, the United States is often seen as the most dominant and assertive Western power, but France still has an independent foreign policy and does not always agree with Washington on how regional or international affairs should be carried out.

Though France is at least nominally supportive of a nuclear deal with Iran, its position and goals are more complicated.

Kiwan told NOW that France is less enthusiastic than the Americans about a renewed nuclear deal with Iran, as the failure to implement such an agreement could potentially strengthen France’s position toward Iran, especially regarding Lebanon.

The US is the main driver of negotiations with Iran, as the Biden administration seeks to pivot away from the Middle East and handoff its security commitments to regional powers. One of the US’s biggest obstacles in making a deal with Iran is Israel’s opposition to any such idea.

Much like France, Israel would not necessarily gain much from a nuclear deal, and it has continually sought to undermine negotiations. This opposition puts the US in a difficult position, as Israel is its strongest ally in the region.

“Israel is a constant, not a variable, in the foreign policy of the US,” Kiwan told NOW.

France also has a strong relationship with Israel, and both countries have a vested interest in a deal with Iran failing to come to fruition. Indeed, Paris would certainly have a plan B to step in as a mediator if a deal falls through.

Colonial legacies and Marine Le Pen’s nativism

In the 19th century, the belief that France had a duty to defend Christians in the Middle East became commonplace after the massacres of Christians in Mouth Lebanon and Damascus in 1860 during the Ottoman period. This belief also conveniently justified French geopolitical interests in the region and its eventual colonial dominance over Lebanon, Syria, and North Africa.

Though France is no longer a colonial power, the idea that the French must protect the Christians of the East has persisted.

Macron and Le Pen have both referenced this concept, but Kiwan and Mhanna indicated that it was a critical aspect when discussing Le Pen’s position toward Lebanon.

“The position of Le Pen would be to support the Lebanese Forces and… the opposition to Hezbollah… She would be in favor of more decentralization, maybe a reshaping of the map of Lebanon,” Kiwan told NOW.

She explained that Le Pen would be a natural ally to right-wing Christians who desire more autonomy within Lebanon.

Since independence, Lebanese Christians have had an outsized influence over the government and machinations of the state. However, since the end of the civil war in 1990, the Christian community has slowly lost the power it once enjoyed, as Hezbollah and its allies have functionally become the most powerful force in Lebanese politics.

And now, much like when Camille Chamoun proposed partitioning Lebanon in response to the possibility that the left would triumph in the civil war, there are some who would like to see a similar approach to Lebanon’s current woes.

“[Right-wing] Christians can [no longer] control the whole country, so instead of giving up, they would be happy to control part of it,” Kiwan explained.

Le Pen’s nativist political platform is analogous to many of the views held by Lebanon’s right-wing, who view themselves as largely Western people threatened by Muslim aggression.

Mhanna expressed a similar sentiment.

“[Le Pen] will embolden identity-based politics, and give identity-based politics – something that unfortunately Lebanon has known for way too long – legitimacy at a global scale… It will allow some of our far-right… identity-based politicians to continue with their discourse,” he told NOW.

Lebanese Christians living in France may be partial to Le Pen as well.

“If you go to France, especially among the Christian Lebanese community that immigrated in the 1980s, you will see very strong support for Le Pen… She said out loud what would be politically incorrect to say in Lebanon in the public scene,” Mhanna said.

“This very strong feeling that Christians are persecuted and that Muslims are here to replace [them]… this is the general mood among her supporters, so it is quite natural to expect Lebanese Christian right-wingers and nativists to be very open to this type of discourse,” he added.

If you go to France, especially among the Christian Lebanese community that immigrated in the 1980s, you will see a very strong support for Le Pen… She said out loud what would be politically incorrect to say in Lebanon in the public scene.

Mhanna continued that a Le Pen victory would not only embolden the far-right in Lebanon, but also internationally.

He explained that if nativists were to win in Hungary, Slovenia, or Poland, for instance, it would not have global effects, but if a nativist wins in France, it would embolden more far-right leaders across the world.

Paradoxically, a Le Pen victory could actually make Christians’ position in the Middle East worse, as Le Pen’s ideology could send the message that a Christian’s life is more valuable than the life of someone from another denomination. This could then exacerbate sectarian differences and potentially lead to religious persecution, which is already an issue in the region.

France is a major provider of development aid, and Le Pen might also support limiting immigration in return for said aid. This may not necessarily affect Lebanon, but it would certainly affect the broader region.

Somewhat ironically, Le Pen has been critical of Hezbollah but is supportive of one of its main allies, the Syrian government under Bashar al-Assad. Le Pen views the Syrian opposition as Islamic extremists fighting against a secular government. She may not like al-Assad very much, but she still prefers him to any member of the opposition.

If she were to win office, it would only accelerate the normalization of the Syrian government, which has been slowly gaining ground in recent years.

Based on recent polling data, Macron is set to win the election. A continuation of the last five years may not be the best for Lebanon, but it is certainly not the worst outcome either. Though Macron would likely continue to work with Lebanon’s political class, some positive change might occur during another five years of his rule.

David Isaly is a journalist and researcher with @NOW_leb. He tweets @DEyesalli.