If this was the story they wanted it to be, Rami Kaaki and his wife, Safaa, would describe how content they were in their lives. The first weekend of Aug 2020, they celebrated Eid at their country house in Bouarej, in the eastern side of Beqaa Governorate, lunched on homemade food, and played around their pool with their 4-year-old daughter, Lea.

Rami planned on returning to Bouarej the following Tuesday, after finishing his shift at the fire department, to prune his tree and straighten his outdoor setting where he would relax with his pregnant wife and watch over Lea.

But the couple’s destiny, wrought by political corruption and negligence, was altered within minutes.

Rami’s last call

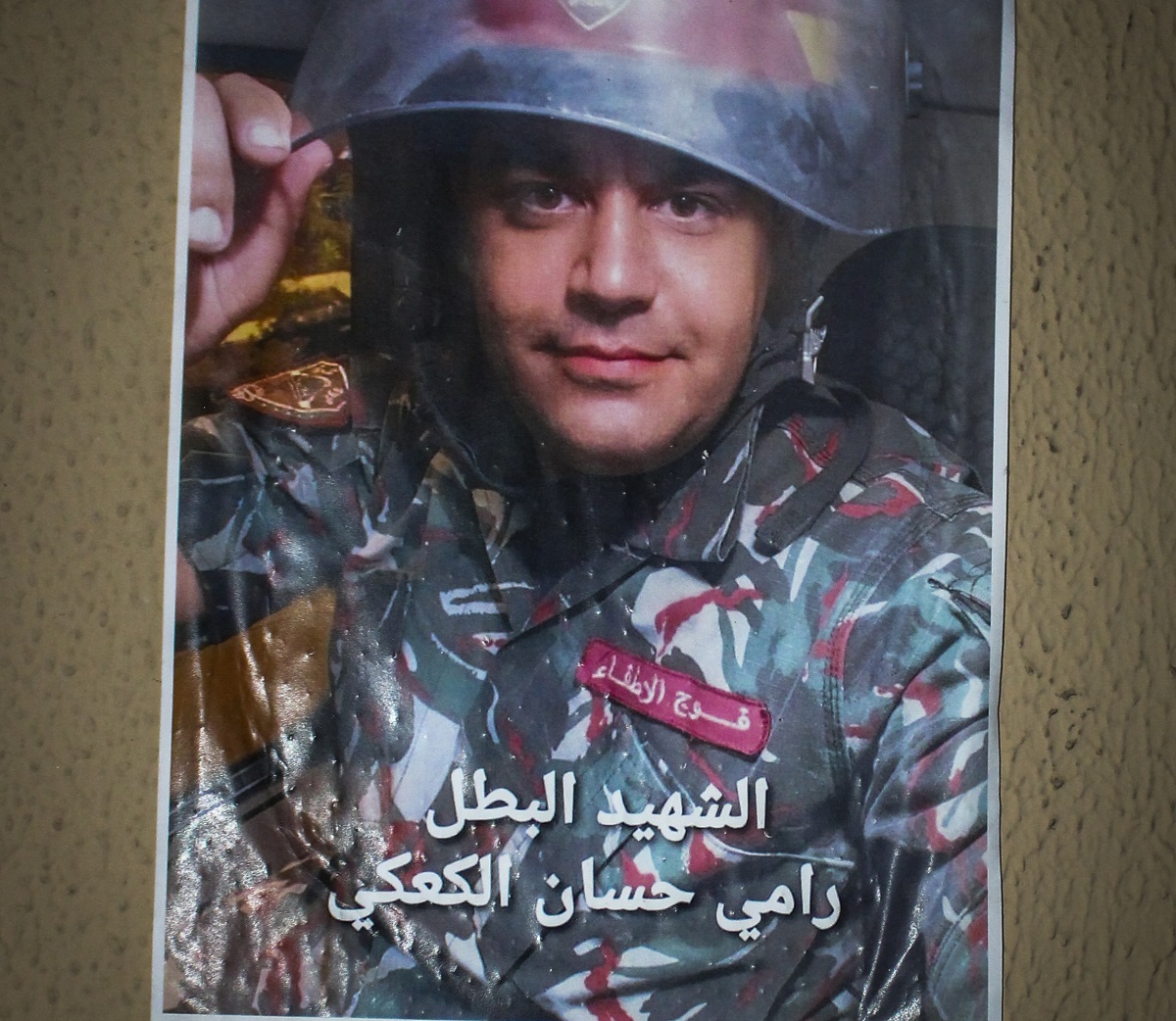

Rami, 35, a firefighter with the Karantina fire brigade, departed for his shift at 1 p.m. Aug. 4. It was the last time his family would see him. He left early that day to prepare for the Beirut governor’s procedural visit to the station.

His wife believes he gave her an inkling of the last goodbye that day. While on shift, he sent his wife a random voice message urging her to look after Lea and help her bloom into a remarkable woman. “It was like a will,” Safaa says, referring to his message. “A death wish.”

Safaa retains Rami’s last messages on her phone, but one year later, she still can’t bear to play them again and hear his voice.

“The last time I talked with him was at 4:30 [p.m.],” said Safaa, who was six weeks pregnant the day her husband died. “He called to check in on me but I was dozing off so I told him I will call him later.”

Rami’s name was not listed to be dispatched on the next mission but upon receiving a call about a fire at the Beirut port, he immediately picked up his jacket and raced to the ambulance driver’s seat.

He arrived at Beirut’s commercial port, with nine other colleagues, where a deadly pile of ammonium nitrate that had been festering in a dockside warehouse for seven years, detonated in one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history, disfiguring over half the bustling Lebanese capital. According to a report released by Human Rights Watch on Tuesday, they were never told that Hangar 12 contained hundreds of tons of explosive material.

Following the explosion, Safaa called Rami to check on him. She wanted to tell him she was fleeing to the mountains with their daughter.

“The toughest thing in the world is when a rescuer needs to be rescued.”

Rami never picked up the phone.

“There was no phone service,” Safaa said. “I tried calling my brothers next but there was no service either, so I didn’t worry.”

Safaa grabbed Lea from underneath her bed, where she was hiding, and rushed toward the car. She was finally able to contact her family members, who informed her the explosion was close to Karantina. She shrieked in pain, knowing her husband was indubitably dead.

“‘Safaa I’m okay. Safaa, set out for the mountains.’ Rami would’ve immediately reached out in situations on this scale,” Safaa said. “He was a perfect example of a family man. If he were held up on that day or couldn’t find a phone, he would’ve begged anyone to let him use their phone to check in on us.”

“The toughest thing in the world is when a rescuer needs to be rescued,” read Rami’s last Facebook status update.

The search for Rami

It took Rami’s family seven days to locate him after the explosion. But his wife was convinced he was slain by half past six on August 4 when he didn’t answer his phone.

Sahar Fares, the paramedic on the team of 10 firefighters who were sent to their deaths, was the first to be located and confirmed dead. Her teammates, including Rami, remained missing for days before they were found, each one on a different day, at a different hospital.

Safaa’s anguish at the tragedy’s enormity prevented her from joining the search for her husband. She was certain he was dead.

Despite her pain, she wanted to remain sane and logical. She knew the chances of finding him alive were slim. “I was trying not to promise myself an outcome I knew wasn’t possible,” she said.

Hoping for closure, she yearned to find his body so she could bury him.

Each family member reacted differently to Rami’s loss.

He was a great swimmer, his mother kept repeating. So, if he were blown to sea, he could survive.

“On that day, we buried him. And I was buried with him.”

His siblings refused to presume Rami dead. Until their brother was found, they verbally chastised anyone who said “Allah yerhamo,” which translates to “may he rest in peace.”

For days, Rami’s family, dragging along a trickle of hope, scoured Lebanon’s hospitals for answers.

At Al Zahraa hospital in Beirut, a body with a tag that read “5/8/2020,” matched 99.9% with Rami’s father’s DNA.

The blast happened on an ill-omened Tuesday. Rami’s body was taken to the hospital the day after, but he wasn’t found until the following Tuesday. Seven days later.

His burial march on August 11 was attended by thousands of people across Beirut, including Rami’s comrades, who carried his coffin.

Safaa opened the coffin to bid her husband farewell and noticed he was still wearing his firefighter duty boots.

“On that day, we buried him. And I was buried with him,” she said.

Rami’s name

Mohammad-Rami Kaaki, who, according to Safaa, is the spitting image of his father,, was born on February 26, almost seven months after the colossal explosion rendered him fatherless.

Not wanting Lea to end up an only child, Safaa wanted to conceive again early last summer. However, due to the meteoric financial crash, Rami thought it was an inopportune time to have another baby.

The Lebanese currency had lost almost 78 percent of its value by June of last year and was trading at LL7,000 to the U.S. dollar on the black market. The country was derailed by its government’s corruption and maladministration and a debt that has been accumulating since the 1975-1990 civil war. The economic collapse ravaged Lebanon’s middle class and drove many into poverty. But, once Safaa got pregnant with little Rami, her husband could not hide his happiness.

“He will grow up and ask me, ‘Why don’t I say, “baba”? Why do all the other kids have a father and I don’t?”

Safaa takes a deep breath, her face etched with grief. Her eyes glisten, then tears stream down her face.

“Rami would not stop saying how much he looks forward to holding the baby in his arms,” Safaa said.

She says she kept down the pain after Rami’s death because she was scared it would affect the baby. “[He] was the last gift from Rami so I was worried about losing him,” Safaa says.

One week before the explosion, Rami dreamed that Prophet Mohammad handed him a baby then said, “Here’s Mohammad.” If their baby is a boy, the couple agreed to name him Mohammad.

To honor her husband’s wish and to keep the name “Rami” alive within the family, Safaa decided to give her baby both names. “Mohammad-Rami,” the name rolled off her tongue.

“He will grow up and ask me, ‘Why don’t I say, “baba”? Why do all the other kids have a father and I don’t?’” Safaa said.

Rami in heaven

Rami’s daughter, Lea, is a preschooler with sleek, chocolate-blonde hair, a breezy personality and an imagination that does not ask to be validated. Lea tells her mother an angel carried her father to heaven where he’s building a home for them.

“She has created an imagery that suits her to explain what happened to Rami,” Safaa said.

“We were forced to play music and act happy but on the inside, we were butchered.”

Lea, who recently celebrated her 5th birthday, her first birthday without her father, was four when she lost him.

“It was very painful,” her mother said. “We were forced to play music and act happy but on the inside, we were butchered.”

Every so often, Lea slips in heavy questions: “Who placed the explosives at the port?” “Why did they take my father?” and “Why did they burn him?”

But Safaa reinvigorates the notion of Rami being taken to heaven by an angel.

Lea’s separation from her father has taken an emotional toll on her. She now gets panic-stricken and struggles to play with other kids, choosing to stay close to her mother instead.

“Don’t leave me,” Lea often tells her mother. When Safaa drops Lea off at summer camp, she frequently asks, “Are you coming back to pick me up?”

Justice for Rami

Safaa, a legal assistant at the Palace of Justice, hasn’t fully returned to work since the tragedy and doesn’t think she ever will. She resents the place that is supposed to prosecute those responsible for her husband’s death but has failed to hold anyone accountable.

Though she works two floors beneath where the port blast probe investigators have their offices, she has no faith in Lebanon’s judiciary system, so she has never bothered to go upstairs to ask about the investigation.

The countdown towards the mushroom cloud that sent a shattering shock wave across Beirut, killing 218 people and wounding thousands, kicked off nearly six years ago when a Moldovan-flagged cargo ship, the Rhosus, carrying 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate made an unscheduled stop at the capitol’s port, according to a Human Rights Watch report.

Ensnarled in a legal and financial wrangle, the ship never left and the shipment was relocated to warehouse No.12 where it would moulder for years.

One year after the blast, no one has been held responsible for their negligence toward the threat posed by the chemical storage. Lebanese officials received requests to re-export the shipment but no measurements were taken.

Kayan Tleis, a representative for a committee of the victims’ families, is confident that Judge Tarek Bitar will secure justice for those who perished in the explosion.

Tleis formed the committee with Ibrahim Hoteit. Their younger brothers, Mohammad Tleis and Tharwat Hoteit, who had died in the blast and were initially listed as missing afterwards. The two men teamed up in the search for their brothers, then more families joined in.

“Even if they give us the truth, it will be fabricated.”

“I didn’t lose my brother only, I lost all those who fell victim to the explosion,” Tleis said, before mentioning the Beirut blast’s one year anniversary. “So on this day, we will remember our big loss.”

Tleis believes truth and justice are the only things that can alleviate a small part of his pain.

On the other hand, Safaa doesn’t want the truth nor does she expect it. She describes it as finding a flower in a pile of trash, the flower having an unpleasant smell.

“Even if they give us the truth, it will be fabricated.”

Attempting to console her, people repeatedly tell Safaa the old Arabic proverb: “Everything starts small and grows bigger except for sorrow, it starts big and gets smaller.”

But this is not the case for her. Her pain is getting bigger with time. After Rami’s death she experienced separation, then came longing, and then loneliness. Her pain grows bigger with every step her children take, with every laugh, with every Eid, with every celebration.

“This is our story and this is how much it hurts,” Safaa concluded.

Sally Abou AlJoud is a journalist based in Beirut. She is on Twitter, @JoudSally and on Instangram @sallyabualjoud.