The visit of the U.S. Treasury delegation to Beirut this week was no diplomatic courtesy call—it was a political warning. Washington’s message was clear: Lebanon stands at the threshold of a new phase. The United States did not come to repeat familiar lines about army support or financial reform. It came to assert that peace and reform are the twin pillars of sovereignty—and that a state unable to control its finances or its weapons can never truly control its destiny.

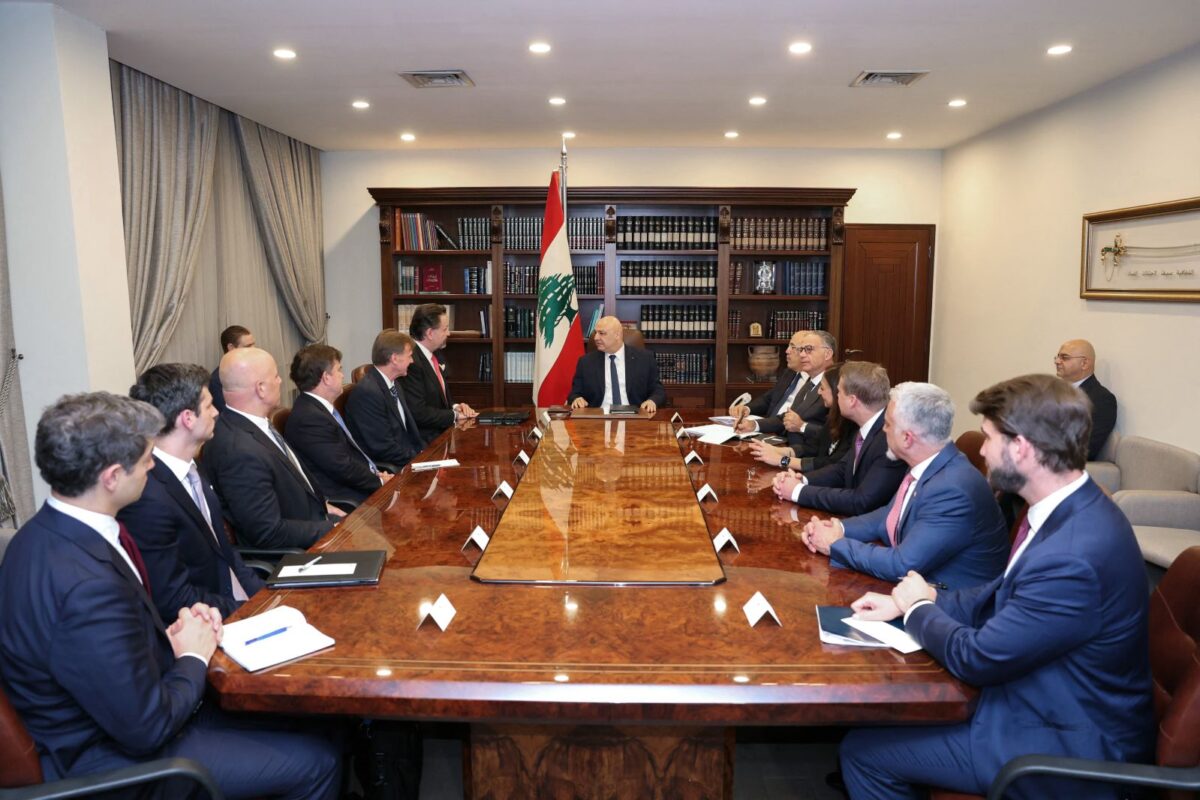

The meeting between President Joseph Aoun and the delegation, led by Dr. Sebastian Gorka, Deputy Assistant to the U.S. President for Terrorist Financing, underscored this shift. President Aoun outlined Lebanon’s measures to combat money laundering and smuggling, amendments to the banking secrecy law, and steps to restructure the financial sector. But the gap between declarations and implementation remains vast. Lebanon has mastered the art of issuing statements, not of executing policies.

What Washington wanted from Beirut was not a list of legal texts, but a vision: How does the Lebanese state intend to reclaim its economic sovereignty? How will it prevent its financial system from serving as a tool for foreign influence—specifically Iran and its allies? The U.S. administration now views financial corruption and political subservience as two fronts of the same battle. Lebanon’s economy, in this view, has itself become a weapon in Tehran’s hands—funding networks of patronage, smuggling, and militias.

Hence the firmness of the American message this time: it is no longer enough for Lebanon to declare its commitment to combating money laundering. It must prove it—with visible action: confiscations, prosecutions, and accountability. The international community no longer measures intent but results. Every delay in enforcement effectively sustains the infrastructure that enables Hezbollah to operate outside the formal banking system, turning the state into a legal façade for a shadow economy.

For Washington, financial reform and political stability are inseparable—two faces of the same sovereignty. Lebanon must move beyond “crisis management” to a phase of trust-building, where transparency becomes the foundation of governance and accountability the rule, not the exception. Reform is no longer an American demand or an IMF precondition—it is a national necessity. An unregulated economy will cease to be a national one; it becomes an instrument of external power.

The Lebanese government must therefore free itself from the pressures of the forces that have long obstructed reform—from Hezbollah to the financial and political lobbies shielding their interests in the name of “stability.” These groups fear transparency more than they fear sanctions. Every genuine reform weakens the networks of smuggling and evasion that sustain Iran’s regional axis. Every retreat strengthens Lebanon’s dependency and entrenches the logic of the parallel state.

A government that allows a militia to control its borders cannot credibly claim to combat terrorism financing. Every smuggled shipment, every illicit transfer, is not just a legal violation but an assault on sovereignty. Lebanon cannot negotiate its future while its economy is held hostage, nor can it build peace while its budget is fed by smuggling and tax evasion. Financial reform, at its core, is an act of political emancipation—from black money and from the weapons that exist outside state authority.

President Aoun, for his part, referred to a draft law addressing the “financial gap” and to ongoing IMF negotiations. But the IMF no longer awaits new statements—it awaits political will. All the numbers are known, all the conditions published; what is missing is a decision to end impunity and start accountability. Real reform begins not in ledgers, but in breaking the bond between power and corruption.

The American delegation, while reaffirming support for the army and its role in extending state authority, made it clear that military aid cannot substitute for political resolve. Peace in the south will not come without completing the plan for exclusive state control of arms and deploying the army to every inch of Lebanon’s borders. Just as President Aoun called on the international community to pressure Israel to implement UN Resolution 1701, so too the world expects Lebanon to honor its own obligations: one sovereignty, one army, one state.

Washington’s evolving tone reflects a deeper conviction that Lebanon can no longer afford stagnation. The country must now enter a new era defined by peace, reform, and accountability. Stability will not be granted for free; aid will not flow without reforms; and international support will not endure if the state continues to shield corruption and illegality.

The greatest danger for Lebanon today is once again falling into the trap of compromise—appeasing Hezbollah by freezing reforms, or placating financial lobbies by preserving opacity. A state afraid to confront its own vested interests will lose both its credibility and its allies. Those who believe silence preserves “balance” forget that this balance is already broken, and that the collapse of trust is far more dangerous than any sanction.

For the United States and its Western partners, Lebanon’s sovereignty and its economic integrity are now inseparable. What they seek is not tutelage but partnership, built on transparency and shared interest. Stability, they argue, begins with reform; peace begins with decision. Continued hesitation will only leave Lebanon as a country without a state, borders without guardians, and an economy without identity.

Lebanon does not lack expertise or laws—it lacks will. Only that will can restore its standing. A state that cannot defend its financial system cannot defend its borders; a leadership unwilling to prosecute thieves will never disarm militias. The first step toward peace is not negotiating with the outside but confronting the inside. There, and only there, can sovereignty be rebuilt and a new beginning written.

This article originally appeared in Elaf

Makram Rabah is the managing editor at Now Lebanon and an Assistant Professor at the American University of Beirut, Department of History. His book Conflict on Mount Lebanon: The Druze, the Maronites and Collective Memory (Edinburgh University Press) covers collective identities and the Lebanese Civil War. He tweets at @makramrabah