The Lebanese Army arrested 20 people in Northern Bekaa Valley and seized 18,500 liters of gasoline that was headed to Syria only during July 8-12.

For several months already, the troops have cracked down on fuel smuggling along the porous Lebanese-Syrian borders, especially in the area of Hermel, controlled by Hezbollah. During June and July, the Lebanese Army confiscated tens of tons of subsidized gas and diesel as it was smuggled to Syria, according to information published by the Lebanese National News Agency. Many more trucks and tankers made it to the neighboring state.

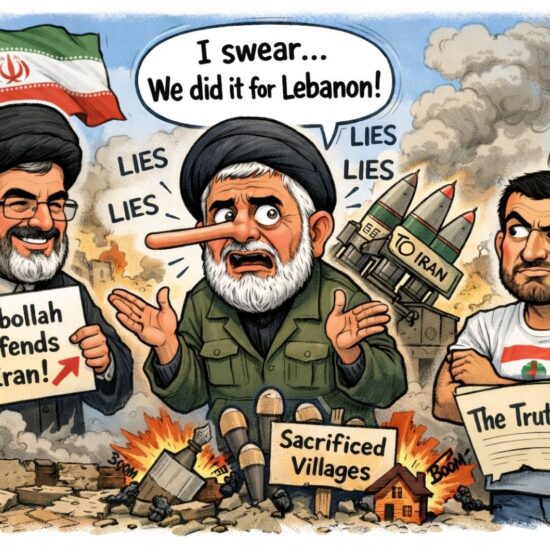

Opponents of Hezbollah accuse the militant party of not only allowing the smuggling to take place, but of taking part in the smuggling itself as a means of making money amid Iran’s economic crisis. Hezbollah denies any involvement in the smuggling.

Because of Iran’s crisis, it has severely limited the amount of funds that it is able to send to its ever-growing militia network throughout the region, forcing the groups to find secondary means to generate income.

“They’ve felt the pinch of the crisis on the Iranian economy,” Iran analyst Arash Azizi told NOW. “Even if you’re Iran and you’re handling these groups, you can tell them to make some of their own money, don’t let it be a one-sided relationship.”

This independent income has seen groups like Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hashed Al-Shaabi in Iraq expand into banking, smuggling and any other resource. In some instances, that means helping each other.

Side hustles

Soon after the Islamic Republic of Iran was established in 1979, the country started to fund armed groups throughout the region in an attempt to expand its influence. The most notable of these is Hezbollah, in Lebanon. Established in 1983, Hezbollah has turned into the dominant political force in the country, relying on Iranian support as well as its own business network and electoral wins.

In Iraq, the network of Shiite militias formed Hashed Al-Shaabi seven years ago to create a united front against ISIS. Hashed was integrated into the armed forces of the state after Daesh was defeated and chased out of Mosul. Then, the bloc moved into politics and won the second-biggest bloc in Iraq’s parliament. With powerful friends in Iran and vast financial assets, the Hashed Al Shaabi also has become the predominant force in Iraqi politics.

Both Hashed Al-Shaabi, also known as the Popular Mobilization Forces or PMF, and Hezbollah have primarily been dependent on Iran for the majority of their funding. But they also help each other.

“Iran intervenes directly in Iraq and provides all necessary resources to support and fund their PMF-backed militias,” Yara Asmar, an expert on Iran and its militant network, told NOW.

However, after former US President Donald Trump pulled out of the nuclear deal that provided Iran with sanctions relief in return for allowing their nuclear facilities to be inspected, Trump began one of the most aggressive sanctions campaigns against the Islamic Republic, crippling its economy.

This has led to a significant decrease in funding for Iran’s vast militia network.

“Lately, Iran stopped funding this fund that’s coming from Iran to support the martyrs who died fighting ISIS,” Asmar explained. “Now, what Hashed Al-Shabi is doing and Iraqi Hezbollah and the Shia militias that are in Hashed Al-Shabi, there was a report coming out about using these kinds of loans like Qard Al-Hassan [Bank] in Lebanon.”

The way the loans work, according to Asmar, is that people pay a deposit in Iraqi Dinar and, in return, they will receive a dollar loan. But the amount that these people need to pay back is astronomically higher than what they may have originally paid.

“This is how they are making money and they are able to support the families of the martyrs who died,” Asmar stated.

In addition to banking, AFP reported that Hashed Al-Shaabi also uses its control over some of Iraq’s ports and border crossings to extort people for bribes.

Hezbollah also has its way of making money to support its operations.

For years, Hezbollah has been accused of smuggling drugs to Europe and Latin America, a charge that the group denies.

“It uses its links to the Lebanese diaspora in places as far as Africa to Latin America, where Hezbollah has a wide presence, and they use it to raise money,” Azizi said.

Most recently, Saudi Arabia banned the importing of Lebanese produce due to the millions of captagon pills that Saudi security forces have discovered hidden in fruit and vegetable shipments over the last few years.

Hezbollah was accused of being behind the drug smuggling, especially after the Lebanese army raided two captagon factories in the village of Boday, Bekaa Valley, a Hezbollah-controlled municipality.

They have also used their connections at the exchange houses throughout the country as a way to exploit Lebanon’s constantly worsening economic crisis and take subsidized goods from Lebanon into Syria where they can sell them for a significant profit.

Hezbollah has also been using the devaluation of the Lebanese lira as a way of making money, using the exchange houses that it runs around the country. This is not only in areas controlled by the group but throughout Lebanon. They then use the dollars that they make to sustain their fuel smuggling operation and the other subsidized goods that are sent to Syria.

Hashed Al-Shaabi also has, according to a banking source that spoke with AFP in June, sent Hezbollah around $60m over nearly two decades. However, Asmar says that this is an insignificant amount since Hashed is limited in how much it can send.

“They [Hashed Al-Shaabi] are also in deep trouble in Iraq and they’re also suffering because of the economic situation in Iran,” the Iran expert explained.

Hezbollah also returns the favor to the Iraqi militias by sending military commanders to train the groups.

“Definitely there is cooperation, but not just exchanging funding and so on,” Asmar said. “What they can do is more of an exchange, having Hezbollah – just like what they did in Syria – officers going to Iraq and training these militias, smuggling weapons to Syria or being there next to them on the ground.”

Asmar also argues that with Iran’s funding decreasing, forcing the groups to find other means to make money, it is pushing the groups to more illegal paths.

“They’re on survival mode and trying to use the system where they operate. And the system where they operate, whether in Iraq or in Lebanon, is disintegrating for many reasons,” she stated. “They will always find ways and the danger for this part is when they start going through more illegal or criminal activities to generate income.”

Despite Hashed Al-Shaabi and Hezbollah’s success in making money independently of Iran, it still is not enough to keep them going, forcing them to continue to depend on Tehran.

“Drones, rockets and paying thousands of men to be full-time soldiers is not a cheap affair,” Azizi stated. “You can’t sell some heroin in Colombia and pay for it.”

Big brother’s pocket

Iran might be in the midst of its own economic crisis, but they are still an entire state with significantly more resources and larger bank accounts than militias, Azizi says.

“[The groups] are limited in expanding their independence because for the simple reason they are militias involved in doing various expensive things and nothing replaces the state coffers,” he pointed out.

“That’s the important thing to remember. Coffers as big of a state as Iran, Iran might be in an economic crisis but it is still a country of 80-something million.”

While it is important for the groups to continue receiving support from Iran so that they can continue operating to their fullest extent, it is just as important for Iran to continue funding groups like Hezbollah and Hashed Al-Shaabi.

Iran has supported the groups finding independent funding, but the Islamic Republic is not going to let them out from under their influence any time soon since the groups help to give Iran a sense of legitimacy when it comes to the “Axis of Resistance” to Israel and the US.

“They [Iran] don’t want to let them go,” Azizi explained. “How can the Islamic Republic have any legitimacy? It has not created a good life for Iranians, even [the regime] itself knows that. It has very clearly not brought prosperity to Iranians or rights. But what it can claim is that it is the head of a vast anti-Israel network of a multi-national army of tens of thousands of people. It is pretty much the only army that seriously fights against Israel. That’s what the Axis of Resistance is all about. So, it won’t give [the militias] up so easily.”

The funding of these militias might give Iran legitimacy in its opposition to Israel and the West, but it also poses a significant burden on the Iranian economy as “the IRGC and Ayatollah Khamenei gave a lot of priority to these groups.”

“[The groups] are limited in expanding their independence because for the simple reason they are militias involved in doing various expensive things and nothing replaces the state coffers.”

Arash Azizi

Azizi believes that if Iran’s economic woes continue and the Islamic Republic keeps giving a large portion of its finances to these groups, then it could spell doom for the Iranian regime and, by extension, for many of the militias.

“It’s not a cheap thing to do,” he argued. “This is something that Iran, just like the Soviet Union found out with many of its international commitments, will become a burden for Iran. In fact, the wide network of Shia militias that have become the signature legacy of Ayatollah Khamenei might prove to become a significant burden for the Islamic Republic and help its undoing.”

The death of IRGC Quds Force commander Qassem Soleimani also dealt a serious blow to Iranian policy in Iraq as it opened up a power vacuum that they are desperately trying to fill as quickly as possible.

“Iran is very much suffering in Iraq, not just with funding, but in terms of strategically operating in Iraq because the death of Soleimani really affected Iran’s operation in Iraq because, unlike Lebanon, Iran is ungrounded in Iraq,” Asmar explained.

“Qassem Soleimani used to go every month to Iraq to check on what’s happening and how things were going. The moment Qassem Soleimani died there was this vacuum in Iraq that for the Iranians is very hard to fill especially that, now, there are rivalries within the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps.”

Iran has made no signs that they are going to cut off payments to these groups, though, and with ultraconservative hardliner Ebrahim Raisi winning the presidency, this policy is unlikely to change any time soon.

The militias, having found moderate success with the independent money-making ventures, will also try to expand these operations in order to make more and more money, but, according to Asmar, their loyalty to Iran is also not going anywhere no matter how much money they might make.

“I see them expanding their network and expanding their activities to be able to sustain themselves financially,” she stated. “But let’s not forget that these groups are ideologically driven. There will not be this disconnection from Iran. This is the raison d’être. The values that Khomeini brought with the revolution, this is what they embrace.”

Nicholas Frakes is a multimedia journalist with @NOW_leb. He tweets @nicfrakesjourno.