A tale of Human Trafficking, Money Laundering, and Rape begs a reform of a juvenile law

Fadi ( nickname ) 15y old is a computer genius since his young age left alone in a room with no family interference nor social life . Very rapidly he was fascinated by systems and hacks leading him to explore the dark web and meeting professional hackers who guided him through method of penetrating operating systems and hijacking passwords. To his luck, or unluck? he was able to discover a “hole” in one of the Lebanese security agencies and compromised stored data. Days after he was arrested by the Cybercrime Investigation Unit at the ISF for questioning. The prosecutor answered positively to a recommendation by the “Union Pour La Protection de l’Enfance “ (UPEL) to use his talents to serve a social community period to help the ISF audit their systems and strengthen their cybersecurity. This is a first. The tale reminds us of the movie “Catch Me If You Can” but is a true case on how deterrence can metamorphose into social gain.

In a country where power cuts are as regular as the sunrise and the internet connection rivals that of a dial-up modem from the 90s, one might wonder: How many people are dwelling into the dark web and do we really deserve TikTok in Lebanon? Let’s explore this question with a healthy dose of sarcasm and a sprinkle of hard-hitting facts.

The dark web escape and usage of TikTok in Lebanon is a microcosm of the larger ethical dilemmas we face as a society. It offers an escape from our troubles but also forces us to confront issues of privacy, censorship, mental health, and inequality. The question isn’t whether we deserve TikTok, but whether we’re equipped to handle its ethical implications. As we navigate this digital landscape, let’s not lose sight of the bigger picture. TikTok may be a fleeting distraction, but the ethical dilemmas it presents are here to stay. It’s up to us to find a balance between enjoying our viral videos and addressing the deeper issues they represent. So, next time you scroll through TikTok, remember: behind every dance challenge lies a challenge to our ethics. To be noted that there has been many calls to ban TikTok in Lebanon however the appeal seems to have faded lately.

The Tik Tok saga

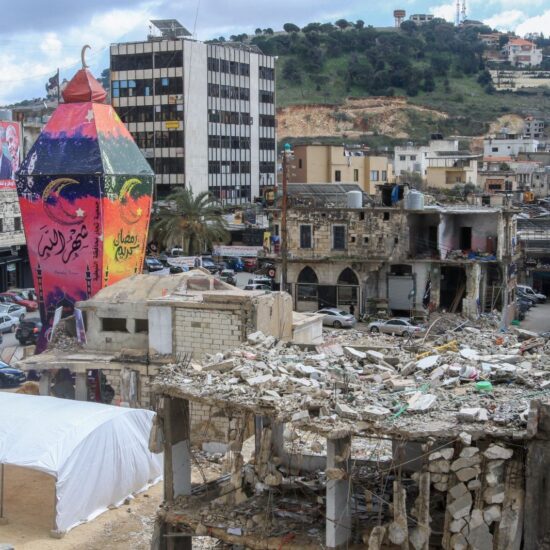

A pedophile gang, including three minors who are influencers on Tik Tok led by a hairdresser who took advantage of his social media fame to lure minors to his barbershop, telling them that they would appear in social media videos while having their hair cut by him. This is one of the many ways that the gang used to deceive the minors online. Reports have also said that “the suspects have documented the acts of rape, then made the victims watch the videos, and blackmailed them, threatening to post the footage online if they spoke out.” They also blackmailed them to get minors to come back and bring their friends. Reportedly the videos were sold on the dark web for amounts starting at USD 500. NOWLEBANON was not able to confirm the news. The dark web has been extensively used here with a connection on VPN making it difficult to trace sources. VPN use is common in a country where internet connections suffer from low speeds. In the same token, a database of 487 million WhatsApp users’ mobile numbers has been put up for sale on the Breached. vc hacking community forum on the dark web. The data set contains information on WhatsApp users from more than 84 countries as reported by Cybernews.

Concerning the Tik Tok affair privacy of juveniles seems to be a major issue, despite the atrocity of the crime committed. I wishwish juvenile names were not published nor their crime nor any details on their lives Amira Sukkar told NOWLEBANON. Sukkar is the president of (UPEL) established in 1936 as an NGO to oversee the children in conflict with the law and the children who need to be protected by the law.

According to her, there has been so much immoral propaganda about this whole affair. Privacy was breached, there was a need to keep secrecy on the whole affair, she added. Sukkar questioned the role of the media in scoring a news scoop which certainly doesn’t serve the judiciary quest for the whole gang of criminals and severely damaged the minor rights she believed. Even if the minors are culprits, these are victims who need professional follow-up, she believes. There has also been an instance of a common move between the ISF and UPEL where a media program was stopped after disclosing intimate accounts of a case involving a minor in Nabatyeh, she disclosed.

Figures published in ByteDance’s advertising resources indicated that TikTok is the most popular channel in Lebanon it had 3.92 million users aged 18 and above in Lebanon in early 2024. In early 2024, the majority of users were young adults aged 18-24, who represent 75% of these users. The next largest group is those aged 25-34, making up 22% of the user base. An interesting observation is that Instagram had approximately 1.95 million users in Lebanon in early 2023, accounting for about 35.9% of the total population. Furthermore, women constituted a slight majority of Instagram’s ad audience at 50.4% in early 2023.

Reform in Juvenile law

Lebanon lacks a complete implementation of a juvenile law according to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). Under Lebanon’s civil law system, ratified international treaties become an integral part of domestic law and are self-executing. Lebanon ratified the CRC on 14 May 1991 and is accordingly bound by it. Lebanon has also ratified the Optional Protocol to the CRC on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography on 08 November 2004. Legal sources who asked for anonymity told NOWLEBANON that there is a need for more impact on the reform to deal specifically with minors. At the heart of this is a much-needed reform in the Department for Minors, integrated in the Ministry of Justice. The focus of this department is the reintegration of juveniles into Lebanese society, as well as developing preventive and protective action plans.

Another key institutional reform Lebanon judiciary has been able to achieve, has been the establishment of the Minors Brigade, a specialized police unit dealing with juveniles, although it is unclear whether or not it is in fact operational. The reorganization of the system of information on juvenile offenders has been equally important. Projected reform of prisons and the conditions in detention centers has also been in the spotlight, as well as training for professionals dealing with juvenile offenders’ affairs, the source clarified. This process of legislative reform in Lebanon has definitely been positive and constitutes an improvement in the protection of minors. To be noted Lebanon tried hundreds of civilians in military courts last year, including children, Human Rights Watch said, urging an end to a practice it said undermines fair trial rights. The rights group said Lebanese civilians can end up in military courts for any interaction with security services or their employees. The group said hundreds of civilians were tried before military courts in 2016, but a precise figure was not available. The Union for Protection of Juveniles in Lebanon said the figure included 355 children. For years, the complete absence of operating procedures on child protection in Lebanon has been a major obstacle in the path of children and all parts involved, towards fulfilling the basic rights of children and ensuring their protection, based on a standardized, legal framework.

Children and their representatives can bring cases in domestic courts to challenge violations of children’s rights. The person or entity permitted to bring the claim depends on the nature of the proceedings and the court which has jurisdiction. For instance, Lebanese law accords the judicial authority the power to intervene wherever a child’s interests are at risk. Article 26 of Law No. 422 of 2002 states that juveniles’ court judge may intervene in order to ensure the protection of children at risk pursuant to a complaint brought by a child, their parents, their guardian(s), those that are responsible for the child, social workers, the public prosecution or pursuant to a report. The Juvenile Judge may also intervenes automatically in cases of urgency.

Economic Contribution of TikTok Influencers

In Lebanon, TikTok influencers have engagement rates ranging from 4.6% to 17.7%, with an average rate of about 10%. This high engagement is indicative of the impactful presence these influencers have.

In a country which boasts a diverse group of 781 active TikTok influencers, with audiences ranging extensively in size from 50,000 to an impressive 25 million followers, a proper judicial control is required. This diversity not only highlights the platform’s reach but also its ability to cater to a wide array of interests and niches within.

The top 200 TikTok influencers in Lebanon are estimated to generate around Usd100 million annually, while the remaining 731 influencers contribute at least an additional Usd50 million. This total of approximately Usd150 million per year underscores the significant economic impact of TikTok influencers in the national economy.

Lebanon, a beacon of technological advancement, where every home is equipped with the latest fiber-optic cables, and 5G towers loom over every corner. Oh, wait. That’s not Lebanon. In reality, Lebanon’s internet infrastructure is as ancient as the Phoenician ruins that dot our landscape. With Ogero, our national telecommunications provider, struggling to maintain basic service, it’s a miracle we can even send an email, let alone stream 15-second dance videos.

Despite these minor inconveniences, the TikTok revolution has taken Lebanon by storm. From the bustling streets of Beirut to the serene mountains of the Bekaa Valley, everyone is jumping on the bandwagon. Who needs reliable electricity when you have the burning desire to create content? After all, there’s no better way to ignore the country’s problems than by perfecting the latest TikTok challenge.

How were minors treated in the Tik Tok case?

Sukkar said the minors did not have lawyers with them during questioning only social workers, on the plus side they were treated very respectfully during their arrest allowing them to move from one room to another without locking them in closed rooms. We made sure that their testimonies were recorded, she added.

According to her, the judiciary has special tribunals for special clusters of cases. We unfortunately lack the luxury to have a general prosecutor specialized in minor cases with a backup system that deals with those cases, she added. The system needs to integrate proper integration of juvenile rights as well as special training on how to deal with minors and related cases she said. Thus the system needs to integrate all including lawyers and stakeholders to ensure a proper safeguard and watchdog for the rights of children she quoted.

Lebanese TikTokers are a resilient breed. Armed with backup generators and battery packs, they navigate the sporadic internet like seasoned sailors. Power outage? No problem. Just light some candles and keep filming. Slow internet? Perfect time to practice patience. Who knew that our daily struggles would inadvertently train us to become social media stars? In Lebanon, a country grappling with profound socio-economic challenges, TikTok has emerged as both a savior and a source of controversy. While it offers a platform for creative expression and a temporary escape from daily hardships, it also raises significant ethical concerns. Let’s delve into the ethical dilemmas surrounding TikTok in Lebanon, blending facts with a touch of sarcasm.

The whereabout of the TikTok Affair

The first investigating judge in Mount Lebanon, Judge Nicolas Mansour, began interrogating 10 detainees from the TikTok gang involved in sexual assaults on children.

The judicial circles are also eagerly awaiting the warrants that the investigating judge will issue against the involved suspects residing outside Lebanon to convert them into international arrest warrants.

At the moment of this report Attorney General at the Mount Lebanon Court of Appeal Tanios Saghbini, indicted 12 individuals involved in the case. Also indicted are another five detainees, including Ghadir Saleh Ghanawi, aka as Gigi, a female suspect believed to have played a significant role in luring children through the TikTok application and then handing them over to the gang.

“The new defendants have been charged with criminal offenses carrying penalties ranging from 3 years to 20 years of hard labor”, a judicial source familiar with the details of the case confirmed.

The source told NOWLEBANON that the “judiciary has charged these individuals with offenses including establishing a criminal network for human trafficking and money laundering, utilizing electronic applications, especially TikTok, using fake identities, luring children, committing violence against them, threatening them with murder and rape, and engaging in indecent acts”.

The judicial source said that the Cybercrime Combating Bureau also has its investigations focused on pursuing all the names that have appeared in the investigation, as well as tracking down all sides involved. Just a few days after a search and arrest warrant was issued against Ghadir Saleh Ghanawi, aka Gigi Ghanawi, the Cybercrime Bureau detained her bringing the total number of detainees in this case to 11 individuals.

A source following up closely on the investigations said that Ghanawi had a dangerous task in luring the children via TikTok under the pretext of securing employment for them in a reputable company.

“She set appointments for them with the alleged company manager, and upon their arrival at the predetermined address, she would receive them at the door of the apartment. Inside the apartment, they would be offered a drink containing a narcotic substance, and then they would be raped”, said the source.

The source added that her most dangerous task was in filming the children being raped, she then sends the photos to the heads of the network outside Lebanon, who were identified as Paul Meouch, known as (Jay), residing in Sweden, and Pierre Naffaa, located in Dubai, in addition to others.

A new list of the names of ten suspects is expected to be issued next week including a lawyer registered with the North Bar Association in Tripoli called Khaled Merheb; and Hassan Sinjer, who according to information is residing in Switzerland. The warrants in absentia will be referred to the public prosecution office which will immediately refer them to the Interpol, according to the source.

“The Lebanese judiciary received positive signals from countries where some members of the gang reside. This indicates that the warrants will be promptly reviewed and executed if they do not conflict with the laws of those countries”, concluded the source.

The Digital Escape a new opium of the masses

Lebanese users flock to TikTok for a respite from the harsh realities of life. From economic collapse to political turmoil, the platform offers a much-needed distraction. Who can blame us for seeking solace in 15-second videos when power cuts and skyrocketing prices are the norm? After all, why dwell on reality when you can perfect your latest dance routine? In an age where data is the new oil, TikTok’s handling of user data is a significant concern. The app’s data collection practices have raised eyebrows globally, and Lebanon is no exception. But let’s be real—our privacy was already on thin ice between government surveillance and data leaks. What’s a little more data mining in the grand scheme of things? TikTok’s algorithm is notorious for promoting certain types of content while censoring others. In Lebanon, this can manifest in the suppression of politically sensitive material. For a country with a rich history of political activism, this is problematic. Yet, amidst our crumbling infrastructure, fighting for free speech on a social media app feels like an oddly luxurious battle.

The addictive nature of TikTok can take a toll on mental health, particularly among younger users. In a country with scarce mental health services, the platform’s impact is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it provides a sense of community; on the other, it can exacerbate feelings of inadequacy and anxiety. But hey, at least we’re all anxious together, right?

TikTok can highlight the stark socioeconomic disparities in Lebanon. While some flaunt their wealth and luxury, others struggle to make ends meet. The platform often becomes a stage where inequality is on full display. Yet, in a country where economic disparity is a daily reality, TikTok merely mirrors the society we live in.

Of course, not everyone can participate in this digital utopia. Rural areas and underserved communities often find themselves on the wrong side of the digital divide. But who cares about inclusivity when you can watch the same influencer lip-sync to the same song for the thousandth time? Priorities, right? One might wonder if our government has any role in supporting this new wave of digital content creation. The answer is a resounding “yes.” By doing absolutely nothing to improve our internet infrastructure, they’ve managed to keep our expectations incredibly low. This way, any slight improvement feels like a monumental achievement. It’s all about perspective.

Tik Tok a response to the harsh reality ??

So, do we deserve TikTok in Lebanon? Of course, we do. The reaction of the bar of lawyers to ban TikTok use for lawyers in Lebanon is ridiculous. If we can survive economic collapse, political instability, and a global pandemic, a little digital distraction is the least we deserve. Besides, where else can you find such a perfect blend of irony and resilience? Every TikTok video in Lebanon is not just a piece of content; it’s a testament to our unyielding spirit and ability to find joy amidst chaos.

Here’s to dancing through the darkness and laughing at our own misfortune, one TikTok at a time. Cheers to us, the true champions of the digital age.

Maan Barazy is an economist and founder and president of the National Council of Entrepreneurship and Innovation. He tweets @maanbarazy.

The views in this story reflect those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of NOW.