With the intensity of the Israeli aggression rapidly intensifying in the country, sectarian tensions are re-emerging, as many Lebanese are facing exclusion, threats, and multiple violence, for being Shiite

Despite being displaced, his neighborhood decimated, his family scattered, his village of origin razed to the ground – for the second time – and most likely occupied, in these hours, again, after the liberation of 2000 – Mahdi insists on paying for the lemonade that we drink on one of the ‘days-after’ the attack. What the bombing was, the number of deaths, the place targeted – Dahieh, Choueifat, Baalback, Nabatieh, Sidon – no longer seems to matter. And not even what day it is, having time transformed into a handful of tasks to complete, in order: survive, get the passports back from the house they fled in a hurry, have enough food supplies, cross the south of Beirut to go to work, find a safer place for the family to sleep. Five people, originally from Markaba, Marjayoun, residing in Sainte Thérèse, Hadeth, between Baabda and Haret Hreik, working parents, a recent graduate in Computer and Communications Engineering, the two younger sisters still students, the two older ones already married. Displaced. Shiites.

It’s hot, and it looks like it’s going to rain: without telling each other, we think of the hundreds of thousands of people on the streets, the one million two hundred thousand displaced throughout the country. They are not to be seen, however, in a desolate Downtown Beirut, where Mahdi Zaraket, 23, works as a data engineer in a French corporate company. “It was my dream, and now it doesn’t matter anymore. I just want to get my family safe, in a proper house, pay the rent, which luckily we can afford, and settle in.” His are kind words, not of anger, not of revenge. He smiles, too. He asks for permanence, after having changed, together with his family, six apartments in what chronological time defines as ‘a week’ – and he perceives as a century.

“It was, I can’t remember, let me check. Monday, or maybe Tuesday. Yes, it was Tuesday, September 24, from our family house, in Sainte Thérèse, we moved in a rush to Mar Elias, to a friend’s place. From there, to an apartment in Jbeil, but it was so bad that we had to find another accommodation, and for two nights we slept in a hotel room there.” It was unaffordable, and too expensive, so – after having stopped at a friend’s at Fanar, Mount Lebanon – he turned to a real estate agent, who found him an apartment in Sioufi, Achrafieh, east Beirut, Maronite Christian Beirut, safe Beirut, with all the buildings still standing, and the sound of the bombs thought to be far away followed by a great silence. No one escapes in a hurry from there: those who could, have already left the country. The houses are restored and empty, very expensive, exclusive to those who, due to religion or place of birth, do not represent a threat.

Lina Bazerji, the owner, didn’t seem to have any problems with people “of a different religion than Achrafieh” – that’s what Mahdi says, and I stick to his phrasing, ‘a different religion,’ not to say Shiite, to avoid arousing getting annoyed, the judging curiosity of those around us, from whom we sit far away, not knowing – not wanting to know – their position regarding the severe crisis of internal displacement from southern Lebanon, the Beqaa valley and the southern suburbs of Beirut, after the last few weeks – the last centuries – of intensified violence. This is the situation in the safe neighborhoods of Beirut: believed to be untouchable, where solidarity does not arise from necessity, but from a predisposition to open-mindedness, from the ability to distinguish a Shiite from a member of Hezbollah’s military wing. Indeed the sectarian tensions, never completely resolved in the country, have gone this far. Although the millions of people who remain are forced into just over three-quarters of the territorial extension of Lebanon – with most of the south and the Beqaa being now uninhabitable – the homes of expats, Lebanese with dual citizenship, and foreigners who left, are deliberately left empty. Crowding Martyrs’ Square, Horsh Beirut, the Waterfront, the Dawra under bridge, and the Ramlet el-Baida beach, with hundreds and hundreds of families who are denied any possibility of refuge: no to overflowing schools, no to hotels with the lights always on yet without customers, no, even, to the possibility of paying a rent. First rows of mattresses, then the distribution of food and blankets, and finally, due to the need to protect one’s privacy, the tents. It is impressive to realize that this is how refugee camps are born in this region and around the world.

The story of Mahdi and the Zaraket family, from this perspective, can be considered a fortunate story. Yet it is, and remains, until justice is achieved, a wrong story.

A wrong story

“I asked the real estate agent in advance if my family and I would have faced any problems in Achrafieh as being from another religion. She said no, that she would have assured us of our good staying with the landlord,” Mahdi starts recalling. “When we first visited the apartment, Lina Bazerji, the owner, was very friendly, she got close to my mum and showed her how to use all the home appliances. Everything seemed smooth, so we decided to rent the place. And we paid, in addition to the monthly rent of 900 dollars, the agent’s fees of 500 dollars, and the electricity and internet bill of 225 dollars. A total of 1,625 dollars, settled before we even got the keys.”

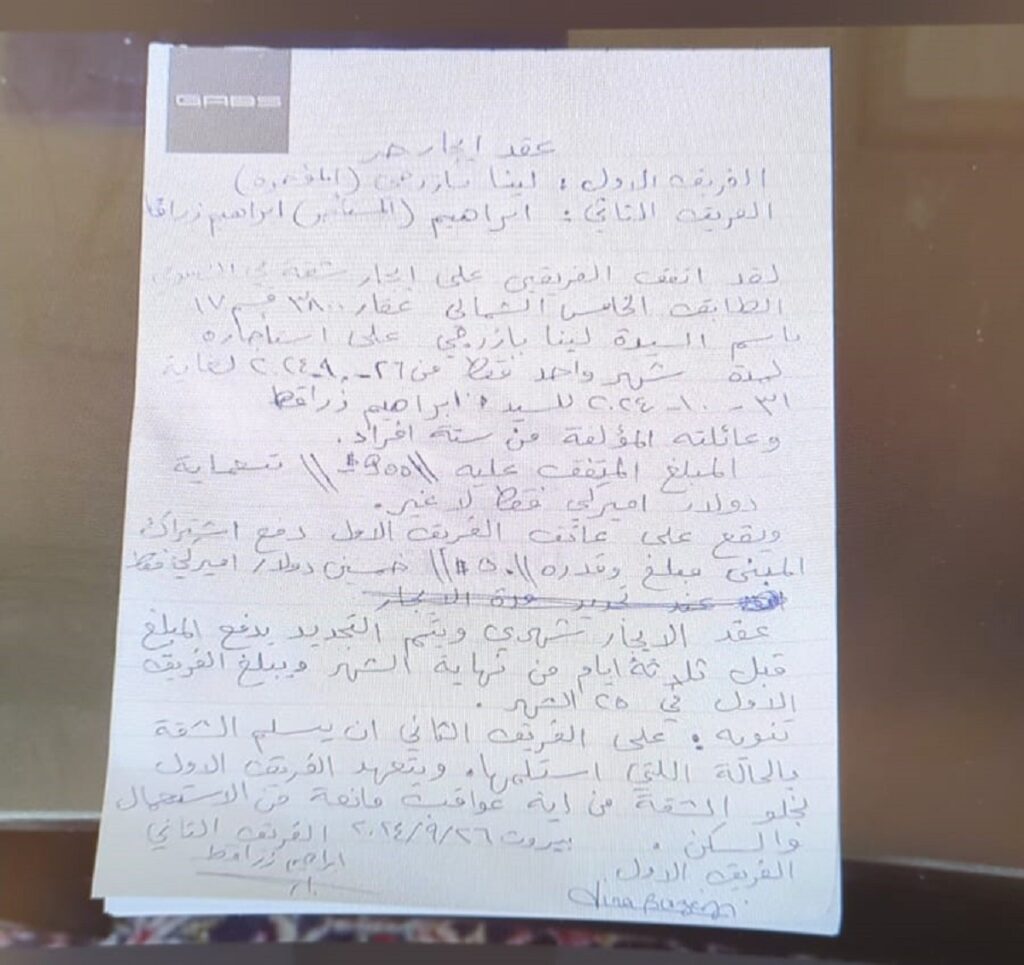

The contract was signed in Mahdi’s father’s name, Ibrahim Zaraket, and Bazerji’s, written on paper, in a very bad Arabic, not clear, and open to interpretation, manipulation, when not fraud – yet legal. It reads: “The two parties have agreed on the rent of an apartment in Al-Sioufi, fifth floor, property 3800, section 17, in the name of Mrs. Lina Bazerji, for one month from 26/9/2024 until 31/10/2024. The tenant Mr. Ibrahim Zaraket will occupy the apartment with his family of six. The agreed upon amount is 900 dollars. The first party is responsible for paying the building monthly charges of 50 dollars. The lease contract is monthly and is renewed by paying the rent three days before the end of the month, and the first party is notified on the 25th of the month. Note: The second party must deliver the apartment in the condition it has received. The first party guarantees that the apartment will be free of any faults preventing use and habitation.”

The original copy of the rental agreement’s contract between Mahdi’s family and the landlord, Lina Bazerji. Kindly provided by the tenants, September 26, 2024

“The following day, before we even tried to settle, Aline, the agent, weirdly asked for all the family members’ IDs, without being clear about the reasons behind the request. I immediately felt uncomfortable with it. When you’re registering a contract, you shall care for the details of only the household, not of every family member. And even in that case, that of the tenants’ personal data is an issue to solve before a contract is signed, not after a displaced family from your own country has already moved in,” Mahdi continues. “And when I asked her if she could wait a few hours, only for a few hours, it got very tense. Aline asked back if we were Lebanese, I said yes, what’s the problem. Mrs. Bazerji, the house owner, was not feeling comfortable anymore. I spoke to my father who immediately called her: all night long, she could not sleep because she was fearing for her own people, for her neighbors. ‘I made a mistake,’ she told my father, ‘I shouldn’t have rented my apartment to you’.”

“That was unacceptable for me. I’d rather leave and find another place than face this pressure on me and my whole family’s shoulders, even if what she asked for was illegal. We paid for a month of rent, we agreed on a written contract. Being displaced does not make us criminals. But I care for my dignity more, I don’t accept to be treated like that. So I left, but I told her: make sure to settle all the amount we paid.”

Again, Bazerji’s answer was delusional: just as the response of half of a country towards the other half of its citizens in need. The 500 dollars of real estate agent’s fees would not have been returned, as well as the internet and electricity bill, services that the Zarakets enjoyed for only one night: “consider as if you stayed in a hotel,” the landlord told Mahdi.

“As if that wasn’t enough, the day we were moving out, while we had an appointment to return the keys at 11 in the morning, my elder sister, pregnant, had her contractions: it was 10.30 am, and she was about to give birth. She lives with her husband, displaced to another area, relatively safe, but to be close to her, we asked if we could keep the apartment for a little more, to drive her to the hospital, wait to see the newborn, then come back and leave.” They did not even have to pack their scattered stuff, so used as they got not to settle down, to expect the worse. They, Shiite, dared asking for a couple of hours, before collecting their grief and disappear. To take part in the most joyful moment in the history of a family’s life: the entry of a new individual into the world – even if the world is this one, unfair, exhausted, wounded as it is.

“There I got mad, and I shouted at her, on the phone, so that at the end she agreed at least to return us the money we paid. But she wanted us out that morning. ‘I am afraid, I can’t do that. You have to leave now,’ she said. So it happened. My sister stayed at her place, without us, yet another time displaced. It was so frustrating, we asked nothing big, nothing difficult. When she came, I told her all of this was unacceptable for us, and we left.”

The action of the verb ‘to leave,’ in this case, is passive – not active. They didn’t leave: they were left. Left behind. And since the Zaraket family had no option when they were left behind, they had to go back to the friend’s house in Fanar: they sat, breathed, and searched from another place. Luckily, an uncle who moved to the safer mountains had an empty apartment in Dohat El Hoss – yet open to welcome other displaced families. North of Naameh, south of Haret Chbib, Khalde, the airport, and the southern suburbs – all the way that Mahdi has to cross on a daily basis now to reach his work.

“At the company they were very helpful, they let me work from home every day, if I wanted to. But because I never stopped moving, I couldn’t take care of the Wi-Fi. I can’t know how much time I’m going to spend there. It’s not worth it to settle, everything might be temporary. The 3G is bad, and there’s no signal there. So I’m obliged to come here.”

The former neighbors, the extended family members, everyone that used to be part of Mahdi’s community is scattered to a different spot: Tripoli, Akkar, the outskirts of Beirut. Anytime something happens, he tells me, without even thinking, as an inertial action you cannot oppose resistance to, they pick up the phone, contact everyone, ask are you good, are you fine, then wait for them to answer, or at least to make sure they received the message, that the double check of receipt reassures the most restless souls.

“It’s a tough situation, but I guess it’s suffered by all Lebanese.”

Instead, it is not. It would be better, in times like this, for the Zarakets – and for any other family – to stay close to each other, all together: but it’s hard. Not only are the rents skyrocketing, but there’s so much demand that apartments get booked in a matter of minutes. “I find a suitable apartment for us, I call, they tell me: try again in fifteen minutes. And when I try, the house is gone. Rented to someone else,” Mahdi explains.

“They ask if we’re neshin, displaced from the south. And when I answer yes – no, we have nothing available. And the thing is that beyond my work in a French corporate company, I graduated from the Amjad High School, in Choueifat, with students from different faiths. My close friends are from all religions, I travelled several times to Europe, I’ve been in Germany, Spain, Belgium. I am not narrow-minded. Everything about me states that I’m not… You know what I mean.” He means – he’s not a militiaman. “I’m a young man, I’m 23, I work in a French company. What else do you need to know? That should be enough. I’ve never been treated this way before.”

On the same day Mahdi and his family were illegally kicked out from the house they rented in Achrafieh, his uncle faced a similar outrage in Tripoli, where his landlord threatened him to get out of the house – or he would have raised the rent to 5,000 dollars. In Saoufar, Mount Lebanon, the same happened to one of his childhood friends: she’s been told to leave, just because Shiite. And it does not end here. The level of sectarian violence in areas of the country considered safe – safe from Israeli bombardments, not from other forms of aggression – has reached the point where another of Mahdi’s neighbors, also in Tripoli, when arrived in Saht en-Nour square, the neck tattooed with a calligraphy of Imam Ali – one of the most obvious religious symbols of Shiism – was said, verbatim: hide your tattoo, or I will break your neck. Five other people approached him and started threatening him, so his wife began to shout, and the van driver moved them somewhere safer.

Not to mention that mini-buses were taking more than 30 dollars per person to get people out of Dahieh, when the strikes’ escalation suddenly began – and the landlords ‘human enough’ to accept Shiite, for example in Chouf, are now asking rents as expensive as 6,000 dollars per month, or 3,000 with six months to pay in advance and 1,000 as deposit. “I’m not going to pay 20,000 dollars for a place that will probably get bombed,” says Mahdi. “The offensor is Israel, not us. But whoever takes advantage of our catastrophe, to me, they’re like Israelis. If they invade south Lebanon, they won’t stop. Just as they did in Palestine. This matter concerns every Lebanese, yet some of us seem not to understand.”

A known story

“We’re from Markaba. You know Palestine? There’s Palestine, Odaisseh, and then Markaba, right on the borders. We have a house there, but since the war started we haven’t been able to go, so we don’t know if it’s still standing,” the young man recalls, while showing a map of the border areas, barely believing that the ground invasion has indeed begun, the war being fought, inside the Lebanese territory, at this same time while we speak.

A map of south Lebanon border area with a highlighting on Markaba, the Zarakets’ village of origin, August 2006. Source: Wikipedia

In Mahdi’s gaze there is the incredulity of someone who witnesses a historical moment with the awareness of its exceptionality: grown up with his parents and grandparents’ memories of the civil war, he knows, now, that tomorrow it will be his turn to tell similar stories to the children and the grandchildren. “If we survive,” he adds with cynicism.

“The elderly know. A few days ago, my grandmother was recalling the days of the Israeli occupation, she still remembers clearly how they used to threaten them, even if they were just children, how suddenly they would enter their houses and search, and they had no more space. It’s the reality of the occupation. That’s why older people don’t care about dying as much as they do about preventing the occupation from happening again. They know the grief of occupation, they know how to deal with it: we were raised with the idea of the liberation and safety of our land, above all.”

Of a closer war, that of the summer of 2006, Mahdi has first-hand memories: he was five years old, and with his entire family they had moved to Bchamoun, at his grandfather’s, on the mountains. He doesn’t remember it clearly, in his mind only a hint of what the war meant, but, he tells me, while the buzz of the drones above our heads does not stop disrupting our dialogue, “the core memories of the period I spent there are not that bad. Because all my family was there, and I used to play a lot wit my cousins. I do remember some bombings, warplanes, but the main feeling left is that of a playful, joyful time.”

And if the parallelism is not already evident enough, when his younger sister, a few days ago, in the midst of the most violent escalation since the beginning of the war, turned 13, they baked her a cake, despite the ongoing displacement, they celebrated together, in a soulless house, without souvenirs, that they have already left, again. “You always feel you’re threatened. But also – no matter what – you have to continue living.”

I ask him about the meaning of home, about which one – among all the houses he inhabited – is the closest, the most adherent to his soul. Last time Mahdi visited Markaba, on the borders first struck, then invaded by Israeli soldiers, was one year ago: yet, his family kept on going until the last summer months. He preferred to stay in Hadeth and invite over his friends there: that one is the house, in Sainte Thérèse, not far from Haret Hreik, he suffers so much in losing. Still standing – despite all buildings as far as 100 meters having been razed to the ground. To abandon a house, after all, is a bit like mourning.

“This morning,” he tells me, “I passed by the house to check on it. But all the surrounding neighborhoods were destroyed. I couldn’t even pass by car through the streets, as it’s full of debris. Not one single person, a couple of cars passing only. It felt so nostalgic. I started remembering ah, that’s where I used to sit or to go, the grocery shop, my morning walks. Now it’s all gone.”

The suitcases of his parents and sisters were already packed, that Tuesday, two weeks ago feeling like an age, when they left: they were ready to evacuate since the summer. Only his, Mahdi’s bags, were not. “I said khalas, when it happens, it happens.” Perhaps, unconsciously, he had left an excuse to return to say goodbye, to take a last, emotional look at the furnishings. “It’s a goodbye, for now. Maybe next time I go there won’t be any house in Hadeth, maybe this afternoon it will be bombed for good, who knows. We got used to the idea of losing our home. It’s been more than a year that we haven’t known anything about our house in Markaba, but what can we do?” he wonders, the buzz of drones above us becoming unbearable.

It is a matryoshka of displacements, of houses and neighborhoods devastated, from the outside, more exposed, layer after layer towards the inside, considered safe. At least for now. Safe and inaccessible, in this unbalanced and disproportionate country, in which the upper floors of the buildings remain lighten-up albeit empty, and the streets – dark, yet packed with thousands of people. And it is not the force of gravity that pushes the Shiites downwards, onto the sidewalks, or under the chasms of the raped city. It is sectarian hatred, the fear of the other than us that precedes any civil war.