July is supposed to be the month in which schoolchildren across Lebanon take their exams for their intermediate (or brevet) certificate. These mark the end of intermediate school and the beginning of high school for students.

However, last month, the Lebanese cabinet – still embroiled in a seemingly interminable battle for legitimacy – announced that this year’s exams would not go forward, in a decision that has confused and outraged many.

In a public statement, caretaker Education Minister Abbas Halabi said he was forced to “cancel the official exams for the intermediate certificate this year and carry out the ones for the high school certificate only.”

“Right now in Lebanon, the brevet certificate is the only way that allows us to assess the educational level of students transitioning from intermediate school to high school,” he added. “There are Lebanese educational bodies – and even political parties – that consider the brevet certificate as a psychological burden for students and their parents.”

This is the latest setback to befall the Lebanese education sector, which has been struggling since the onset of the country’s economic crisis. Earlier this year, teachers’ strikes forced around one million children out of school as educators protested slashed salaries and pensions, leading to demonstrations in front of the Ministry of Education. University students have refused to pay soaring tuition fees, and many have accused the government of succumbing to sectarian infighting instead of working on a solution.

“The problems come from the whole situation,” Principal Charbel Batour, Principal for Collège Notre-Dame de Jamhour, told NOW. “It’s the economy. It’s political. It’s all the social problems of our country.”

“Funding has been a major problem,” he continued. “We were very aggressive in fundraising [and the] teachers accepted some sacrifices in order to deal with the situation. The government, at least for the time being, is absent. We are receiving a lot more from benefactors and donors.”

The rise of the US dollar against the Lebanese pound has led to significant increases in tuition fees as schools scramble to cover ballooning operational costs, while teachers’ salaries have become increasingly devalued as a result of out-of-control hyperinflation. Some private schools are able to secure contributions from alternative sources, but public sector schools are being hit hard, especially in more rural areas where resources are scarce.

There is currently no support for schools from the government because they are unable to do so. The intervention of [NGOs has] prevented some schools from closing their doors.

Going into the academic year 2023-2024, the cost of education is projected to rise to $550, on average, per child. The average monthly salary in Lebanon has decreased to fewer than $200 dollars. Without access to their own savings – due to a freeze on bank accounts in US dollars, implemented by financial institutions to prevent mass withdrawals – many families are being forced to choose between sending their children to school and keeping a roof over their heads.

Lebanon once enjoyed a preeminent position in the Arab world, with one of the highest standards of education in the region, but the current crisis has exposed severe shortcomings in the country’s education system. In a recent UN study, almost one-in-three Lebanese students aged between 15 and 24 were found to have dropped out of education.

The COVID-19 pandemic complicated matters further, forcing shutdowns across many public sector schools, leaving many students unable to attend classes. While other countries adapted to online learning solutions, Lebanon’s electricity shortages and constant blackouts – along with rapidly rising utility bills – severely disrupted the implementation of any such strategy.

Some people in the government are trying – striving – to do something but, in general, the government is not [making] the right and the needed investment. Unfortunately, this is the only thing that remains [in Lebanon]; we have nothing to give our young people, except education.

Without effective action from the state, NGOs – like the Lebanese Organization for Studies and Training (LOST) – have been forced to step in to shore up Lebanon’s struggling education sector.

“Between 2020 and 2022, children were unable to obtain quality education in the absence of a strategy by the government to support distance education,” said LOST Education Program Manager Omar Bayan. “[There is no] clear plan by the authorities to develop the educational sector, and a lack of development of educational curricula.”

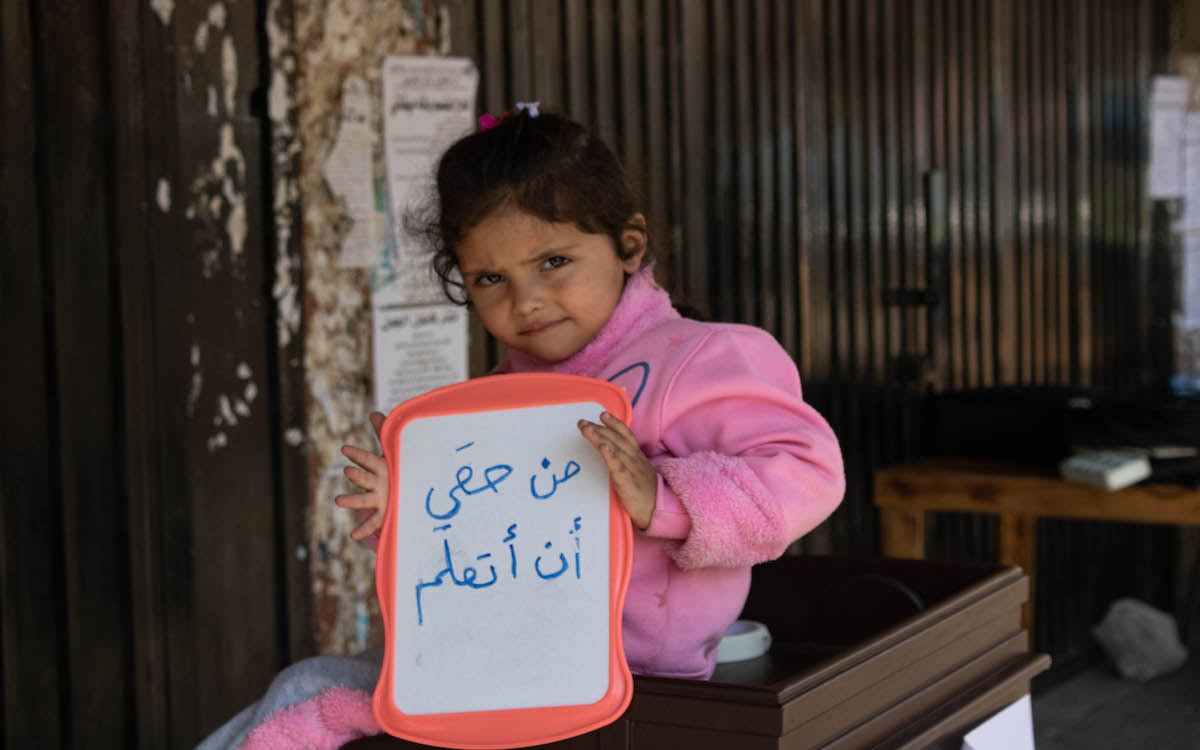

LOST supports public and private schools by providing academic support for teachers and educational staff, and material aid such as solar panels and security cameras. At the same time, they help vulnerable students by preserving their access to learning, especially for young girls.

“Schools are currently relying on reducing their expenses by cutting the number of teaching days,” Bayan added. “There is currently no support for schools from the government because they are unable to do so. The intervention of [NGOs has] prevented some schools from closing their doors.”

“Some people in the government are trying – striving – to do something but, in general, the government is not [making] the right and the needed investment,” echoed Batour. “Unfortunately, this is the only thing that remains [in Lebanon]; we have nothing to give our young people, except education.”

The mounting deficit within Lebanon’s education system has far-reaching implications. With little in the way of manufacturing infrastructure or industrialized agriculture, and the once prosperous financial and tourism sectors in tatters, the lack of a clear rescue plan for schools and universities threatens to gut the country’s most valuable and vital sectors.

Many professionals and technical specialists – and especially students – are choosing to leave Lebanon in search of better-paying positions and greater financial security abroad. If this trend continues, Lebanon will be left with a severely diminished skill pool, potentially for decades to come.

“The ‘brain drain’ will negatively affect the development of the country,” warned Bayan. “The fear is that [emigrating] will be the focus of attention for future generations and that the goal of every innovator and excelling person will be to travel and work outside the country.”

NOW approached the Ministry of Education directly for an official comment but has yet to receive a response.

Robert McKelvey is a multimedia journalist with @NOW_leb. He tweets @RCMcKelvey.