Lebanon’s political leaders have been obstinate in their refusal to implement reforms, despite the country’s deteriorating financial and economic situation. For over three years, Lebanon has been mired in financial difficulties, with a local currency that has lost nearly 99 percent of its value and depositors locked out of their bank accounts.

Out of all foreign assistance channels, civil society organizations, and political parties, Hezbollah has been the most “sinfully” resourceful in managing the crisis.

Access to alternative sources and organizational expertise allows the group to maintain military structure during the crisis. They’re employing temporary survival strategies while still holding on to their independence from state institutions, discouraging their followers (primarily Shiite Muslims) from taking part in unrest. However, their independence from the state and ability to obtain external funds to pay their members’ wages has kept them in high regard among their large constituency.

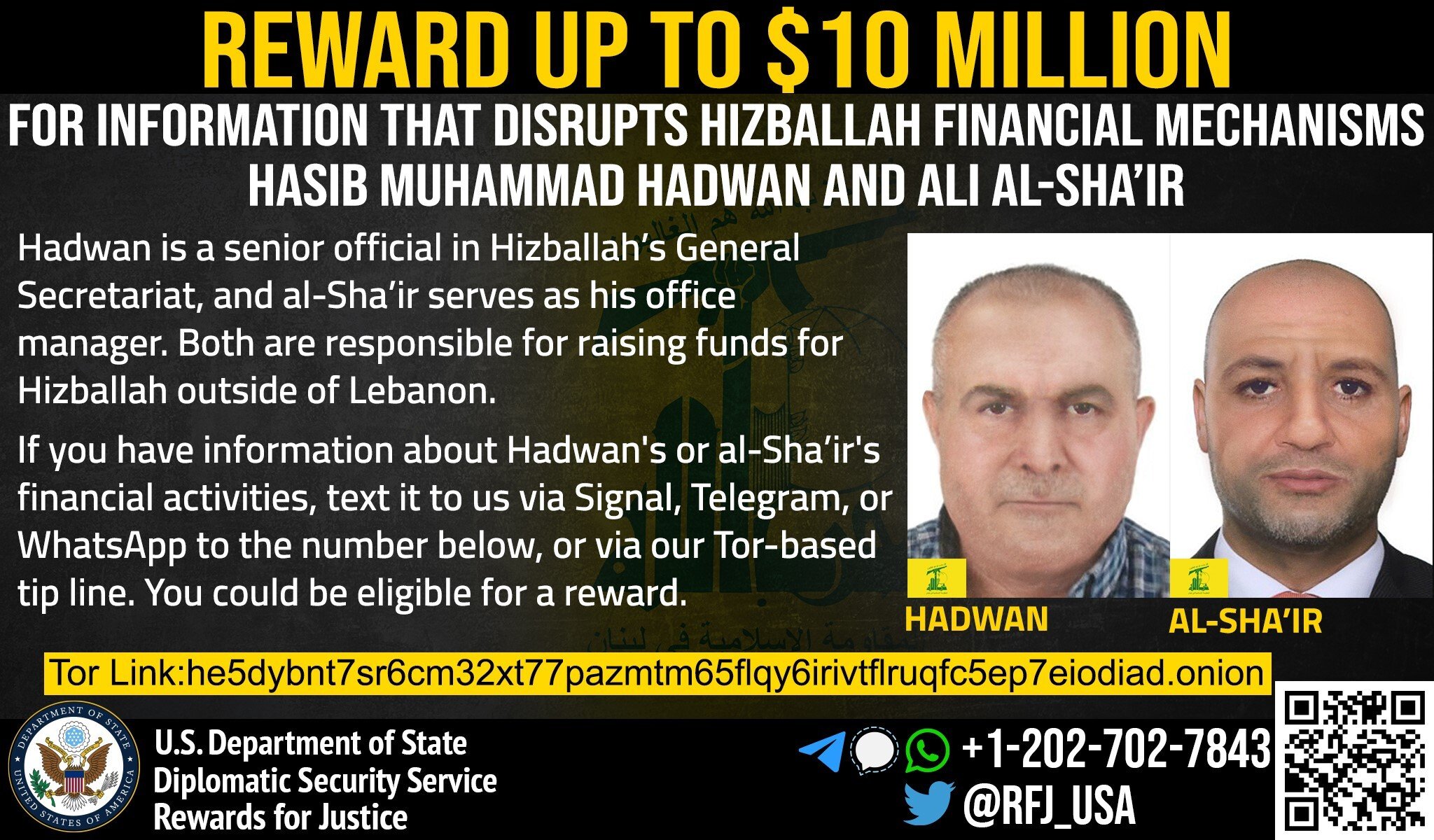

Despite the fact that the group has been hit with a slew of US sanctions that have targeted not only them as a party, but also financial transfers that are vital for Lebanon’s economic stability. Recently, the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) identified a significant transnational network involved in money laundering and the evasion of sanctions. The network implicates 52 individuals and entities hailing from an array of countries, including Lebanon, the United Arab Emirates, South Africa, Angola, Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Belgium, the United Kingdom and Hong Kong, according to the Treasury’s website.

While experts believe that the party will remain largely unaffected, further insight into the party’s practices and its ties to black market exchangers remains crucial in order to fully comprehend the effects on Lebanon.

Over the last decade or so Hezbollah has built its own shadow economy, one which stretches from the shores of the Mediterranean all the way to Ciudad del Este, Paraguay, where they have set up an elaborate network that trades in cocaine, and an assortment of other illegal activities.

Ironically, former president Obama’s zeal to conclude the Iranian nuclear deal drove him to suppress the findings of Operation Cassandra, a global operation that the United States Drug Enforcement Administration launched in 2008 which was able to prove how “Hezbollah had transformed itself from a Middle East-focused military and political organization into an international crime syndicate that some investigators believed was collecting $1 billion a year from drug and weapons trafficking, money laundering and other criminal activities.”

This scandal, which Politico broke in December of 2017, highlighted how Hezbollah and other Iranian proxies had formed their own network of global crime syndicates to access the drugs, weapons and prostitution markets, and thus rather than pursuing its so-called goal of liberating the world of “western hegemony” became exclusively invested in racketeering for its own sake.

Operation Cassandra also revealed how Hezbollah was making use of the Lebanese banking system and transformed some of the banks to the service of their money laundering operations.

Consequently, Hezbollah invited sanctions on a number of banks – amongst them Lebanese Canadian Bank Sal and later Jammal Trust Bank – paving the way to the ultimate exposure of the Lebanese economy and its banks and the ultimate collapse of its financial system in 2019.

As a result, Hezbollah turned to the black market and heavily invested in an elaborate network of money exchangers to move its blood money, as well as to gain access to Lebanon’s subsidized economy.

People walk past a branch of Jammal Trust Bank in Beirut’s Hamra Street on August 30, 2019, in the Lebanese capital. Photo: Anwar Amro, AFP

The network of money exchangers

Hezbollah is known for its large presence in Lebanon’s black market and currency exchange sector. The group is believed to have built a sophisticated financial network that includes currency exchanges, front companies, and other businesses that facilitate the cross-border movement of funds and laundering of illicit proceeds.

According to an anonymous source who spoke to Al Arabiya, the role of Beirut’s Southern Suburbs (Hezbollah’s stronghold) in manipulating exchange rates through dollar buying and selling, remittances, and cash fluctuations was an unlicensed operation located in the Southern Suburbs. It is also said to be the location of an illegal currency exchange office. It has enormous financial capacity, estimated to have a value upwards of $1 billion, to control the dollar exchange rate.

Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah said in a June 2020 speech, “We are bringing dollars into Lebanon, we are not collecting them. Dollar manipulation is a conspiracy to bring down the country.”

The statement suggests that serious currency manipulation is being carried out by unauthorized and illegal foreign exchange bureaus in the southern suburbs of Hezbollah’s home base of Beirut. Nasrallah’s statement suggests that Hezbollah is not involved in dollar manipulation, but rather is bringing dollars into the country. However, sources suggest that the power of unlicensed and illegal money changers in the southern suburbs is being used to control the dollar exchange rate.

This has come to light with the recent arrest of Mahmoud Murad, the head of the Syndicate of Money Changers in Lebanon, on charges of manipulating the exchange rate. Presumably, he bought the dollar at a high price, sold it to wholesalers and made a huge profit with the help of some bankers. Murad’s brother, Yahya Murad, a member of Hezbollah’s “Jihadi Finance” unit, is another major player in the dollar market. Based in southern Beirut, he and his brother ran a company that buys dollars at above-market prices, helping to boost the dollar exchange rate in that area.

Hassan Moukalled

The first wave of sanctions in 2023 began in January when the United States imposed sanctions on a senior Lebanese economist who allegedly supported the financial operations of Hezbollah.

The US Treasury Department announced sanctions against Hassan Moukalled, an economist and money changer, as well as CTEX Exchange, a money services company he owns, and Moukalled’s sons, Rayyan and Rani Moukalled, for facilitating “financial activities in support of Hezbollah.”

Moukalled, who regularly appeared in local media as an economic analyst, “worked closely with senior Hezbollah financial officials to help Hezbollah build influence in the Lebanese financial system.” He is said to have served as the militant group’s finance advisor, and “represents the organization in transactions throughout the region.”

The company, run by Moukalled, gained a significant market share in the currency exchange sector in Lebanon within a year. It collected millions of US dollars on behalf of the Central Bank of Lebanon (BDL) while also providing dollars to Hezbollah-run institutions and recruiting exchange dealers loyal to the party. Moukalled reportedly receives daily commissions of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Despite the severe and ongoing financial crisis in Lebanon in mid-2022, Moukalled worked with Hezbollah officials to capitalize on the efforts of investors and expatriates to make money in the Lebanese financial sector and transfer cash outside Lebanon. Moukalled also aimed to expand the company beyond the country.

Moukalled, who works closely with U.S sanctioned Hezbollah finance official Mohamed Kasir, is said by the Treasury to be representing the party in negotiations with potential investors and partners, as well as foreign government officials. It has been pointed out that Moukalled has coordinated various operations with Kasir, including a trade deal with Russia and efforts to help Hezbollah acquire arms. Moukalled even publicly acknowledged his role as an intermediary in negotiations between the central bank and Hezbollah in 2016, according to a US Treasury statement.

His eldest son, Rayyan Moukalled, has worked with Hezbollah official Mohammed Qasim Al Bazzal on issues related to finance, while his younger son, Rani Moukalled, has been authorized by his father to engage in cash transactions on behalf of their business with BDL.

What is CTEX?

According to the Treasury’s statement, Moukalled received a license for CTEX from BDL in mid-2021 to transfer money within and outside Lebanon. Within a year, the company had gained a huge market share in Lebanese money transfers, reportedly raising millions of dollars for BDL. Simultaneously, CTEX provided US dollars to Hezbollah institutions and recruited Hezbollah-aligned money changers. Moukalled is said to have supported CTEX directly with Central Bank Governor Riad Salameh, collecting hundreds of thousands of dollars in commissions per day.

According to the Treasury, Moukalled set up CTEX as Beirut’s new financial front, with Kasir and his deputy Mohammed Qasim Al-Bazzal behind its establishment.

While Lebanon and its people were under huge economic pressure in mid-2022, Moukalled, in cooperation with Hezbollah officials, leveraged the efforts of investors and expatriates to monetize the Lebanese financial sector and move cash out of Lebanon.

Two other companies owned or controlled by Moukalled were also targeted, namely the Lebanese Company for Information and Studies (LCIS) and the Lebanese Company for Publishing, Media, and Research and Studies (LCPMR).

In an interview with Reuters, Moukalled denied the claims of illegal activity, saying that “We will take all legal measures to respond to this in Lebanon and the U.S.”

In this handout picture released by Lebanon’s Central Bank on November 24, 2022, the governor of the Central Bank Riad Salameh stands next to stacks of gold bars on shelves at the bank’s headquarters in the Lebanese capital Beirut. Photo: Central Bank of Lebanon, AFP

Ali Nemr Khalil

In addition to the impact of the sanctions, those without sanctions could have been affected by the impact of money laundering charges since they could have easily made substantial profits in the parallel market that wreaked havoc on Lebanese lives.

As part of a wave of raids in Lebanon in February 2023, several well-known money changers accused of currency speculation were arrested.

Among them were Ali Nimr al-Khalil, his relative Issa Kanj, and others who are among the most prominent currency traders in the country, according to a local television station.

“A large force from the Information Branch raided the places of a number of illegal money changers in Sidon, arresting three of them and seizing a sum of money from one of them,” MTV reported.

“The raids continued until dawn due to the search for their shops or places of residence,” the TV network added.

Charbel Bou Samra, Beirut’s First Investigative Judge, interrogated the 18 illegal money changers for six hours. The suspects were detained for investigation and were accused of money laundering, violating exchange laws, abusing the financial position of the government and speculating on the national currency.

Khalil had been released on bail for 3 billion Lebanese Pounds and Kanj had been released on bail for 2 billion Lebanese Pounds by the judge. An appeal was filed with the Indictment Division regarding his decision. On April 4, Khalil was released from prison.

Khalil is reported to be closely associated with Hezbollah ally the Amal Movement, and with Nabih Berri, the party’s leader, who has been the speaker of parliament since the 1990s. In addition, Khalil is alleged to have played an important role in the fluctuation of the local currency.

From cash to gold

In April, US prosecutors charged an alleged financier of Lebanon’s Hezbollah with evading US sanctions by exporting hundreds of millions of dollars worth of diamonds and artwork. The accused, Nazem Ahmad, had been sanctioned by the Treasury in 2019 for allegedly supporting Hezbollah. The sanctions were meant to prevent Ahmad and 11 related businesses from accessing the US financial system.

However, federal prosecutors in Brooklyn, New York claim that Ahmad continued to deal in diamonds and artwork with the help of three family members and five associates, who concealed his involvement. One of the alleged co-conspirators, Sundar Nagarajan, was arrested in England in April 2023. Prosecutors estimate that entities linked to Ahmad conducted over $440 million in financial transactions that violated sanctions, including importing $207 million worth of goods to the US and exporting $234 million worth of diamonds and artwork.

According to Américo De Grazia, a Venezuelan opposition lawmaker, Hezbollah has taken over gold exploration mines in Venezuela. De Grazia criticized President Nicolas Maduro’s Orinoco Mining Arc, a large-scale mining project that aims to extract non-renewable resources like gold, diamonds, and coltan from 12 percent of Venezuela’s land.

Venezuela is known to have some of the world’s largest gold reserves, many of which are located in the “mining arc.” However, De Grazia claims that Hezbollah and the National Liberation Army, a Marxist group involved in the Colombian conflict, are exploiting the mining project to their advantage.

De Grazia, who represents the mining state of Bolivar in southeastern Venezuela, alleges that Hezbollah “controls various exclusive mines to finance terrorist operations for the regime it serves,” a reference to Iran. These accusations raise concerns about the potential for terrorist financing and the exploitation of natural resources in Venezuela.

Experts suggest that Western governments’ efforts to counter Hezbollah’s influence in Lebanon by imposing sanctions and targeting the group’s activities may not be enough. As long as the current political system remains in place, Hezbollah’s grip on the Lebanese state is unlikely to weaken. Achieving meaningful change will require comprehensive and sustained reform, led by the Lebanese themselves. Therefore, Western strategies aimed at stabilizing Lebanon should prioritize supporting efforts towards this objective.

What happens now?

In the opinion of Journalist Khaled Bou Shakra, the sanctions may not directly affect Hezbollah. However, if these sanctions continue to expand, they may ruin Lebanon’s reputation among international actors.

“Apart from the economic consequences, sanctions always demonstrate that these networks of money laundering pose a threat to social security and that there are political factions that act independently of the state and feel as though they have the freedom to establish a parallel economy.”

Among the concerns is that Lebanon may be added to the grey list of the Financial Action Task Force, where countries are under special scrutiny to implement standards to prevent the laundering of money and financing of terrorism.

A similar sentiment is expressed by Hadi Al Assaad, Coordinator of the Institute for Finance and Governance at the Higher School of Business, concerning Lebanon’s reputation and rating, which makes dealing with Lebanon from an institutional standpoint – both economically and monetarily – more challenging.

According to Al Assaad, this also limits the ability of the local industry to produce and export products. These limitations make it difficult to expand abroad and reach international markets, preventing the possibility of accessing additional profits and obstructing the flow of funds into the nation.

As the expert explained, exposing money-laundering networks also contributes to the fight against corruption – although Hezbollah may be slow to react if at all possible.

Many of the individuals that were approached, mainly those who served in senior positions at BDL, refused to speak on record or to even give any background information for this article.

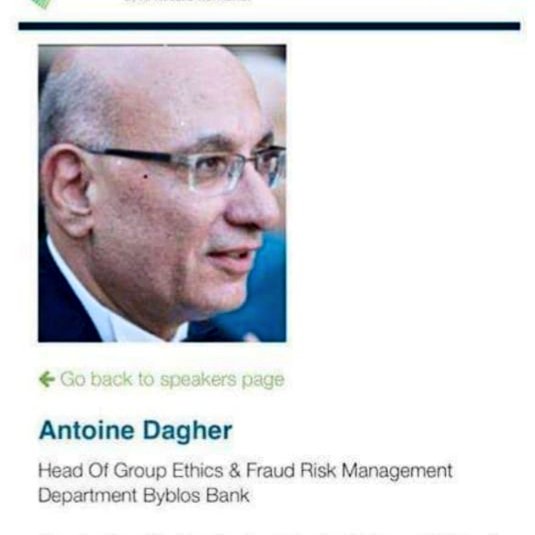

The mysterious murder of Antoine Daher, director of group ethics and fraud risk management at Byblos Bank in June 2020 drew suspicion that Daher had access to numbers that would implicate Hezbollah and a wide network of their Lebanese collaborators. The fashion in which the Daher killing was carried out, and the fact that his murder was intentionally left unaddressed by the Lebanese authorities, underscores the role of Hezbollah in his murder.

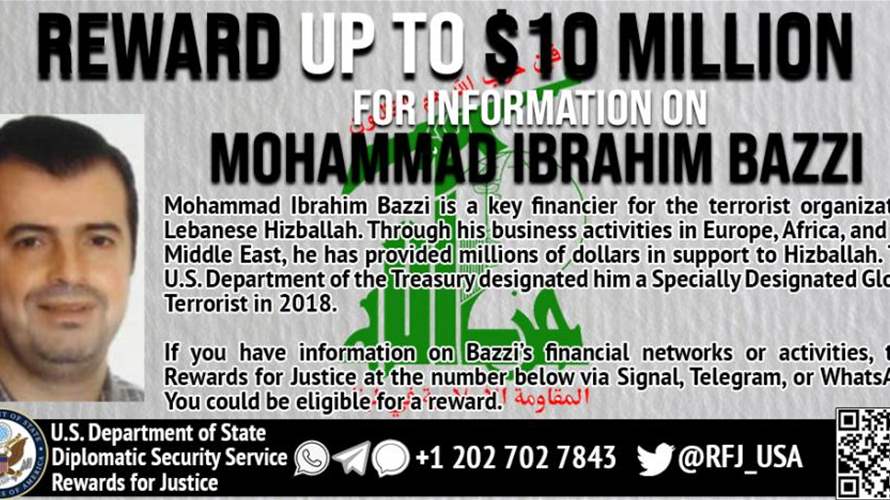

In February 2023, Mohammad Bazzi, along with his alleged accomplice Talal Chahine, was arrested in the Romanian capital of Bucharest on charges of being a key financier for Hezbollah who helped to transfer millions of dollars to the group over the years.

In April 2023, Bazzi was extradited to the US to face charges in a Brooklyn court where he pleaded not guilty to his alleged crimes.

The public at large, including supporters of Hezbollah, are well aware of the party’s illegal activity, and while Hezbollah itself claims that its main preoccupation is with the defense of Lebanon and the Shiites in particular, its criminal activity has led to the destruction of the Lebanese economy and exposed the entire population to hardship. In the case of the Lebanese Shiites, they have become scapegoats for a small portion of the community which exclusively lavishes in the billions of dollars of illegal money it generates from the continued collapse of the countries of the region, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Yemen.

The recent arrests and sanctions only mark a small portion of the expansive local and global financial network that Hezbollah has been able to establish over the decades. In doing so, it ensures that even if some of them are uncovered or arrested, it will have little impact on the network as a whole. If one avenue is shut down, there are several others that they can turn to instead.

The network of criminal masterminds, which now includes the money exchangers, is organically connected to Hezbollah, with people like Hajji Zein and Hajj Salah directly reporting to Hassan Nasrallah, establishing the Secretary General’s implication in amassing money.

In spite of the fact that Hezbollah has been involved in and benefitted from the economic crisis to some extent, sanctions would still act as a possible form of pressure on the political group, even if it is a small one. Sanctions are also important in unveiling the illegal activities of the group, revealing to the people of Lebanon what is happening behind the scenes. Yet for such sanctions to work, as experts explained, the Lebanese at large should force through the economic and political structural reforms which would allow the rise of a strong economy that would single out Hezbollah’s scrupulous and illegal business ventures and bring Lebanon back to the realm of normalcy.