The blue tarp covering the large balcony, protecting those sitting under it from the harsh summer sun, flowed like waves as it blew in the wind.

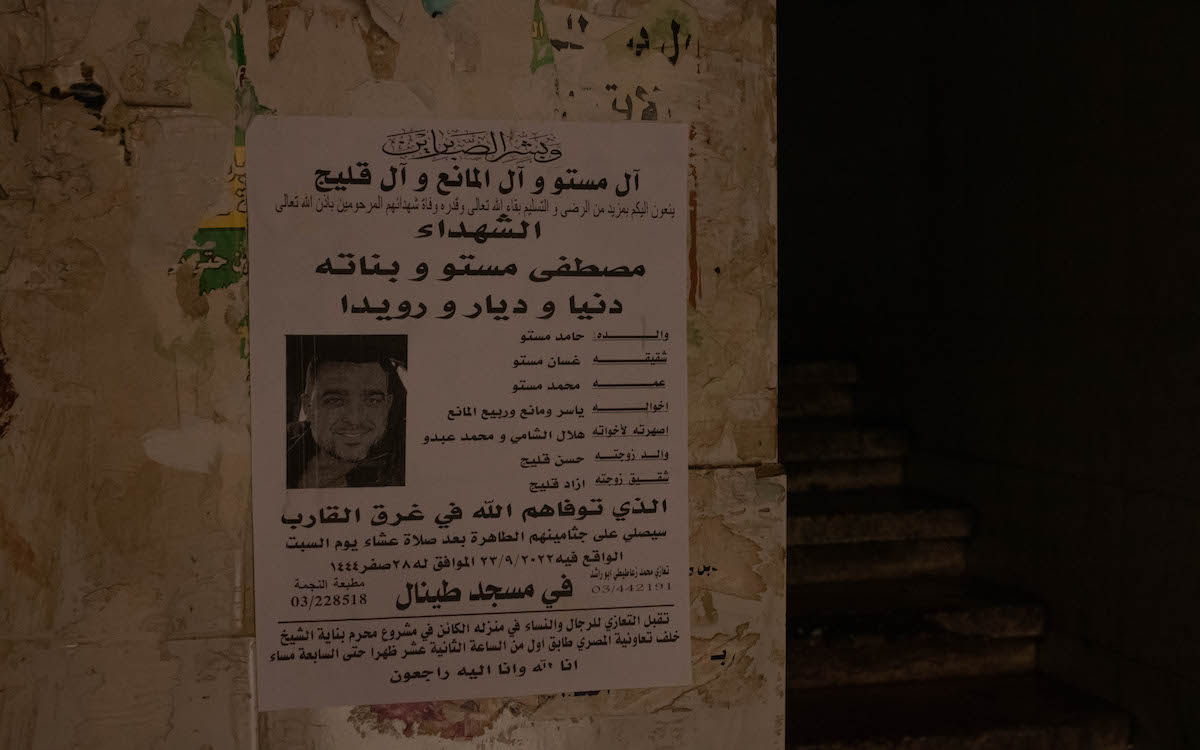

Family and friends of Moustafa Mesto were gathered in the family home to mourn the death of the 35-year-old and his two daughters and son. The four members of the same family died when a boat carrying an estimated 150 people attempting to get smuggled out of Lebanon to Italy on September 22 sank off the coast of Tartus in Syria.

Mesto’s mother, Um Mustafa, well into her 60s, sat in a chair on the balcony, a packet of cigarettes clutched in one hand and her phone in the other which she kept glancing at as if expecting her son to suddenly call and pull her out of this nightmare.

“My heart is aching,” Um Moustafa told NOW, her voice barely audible as she struggled to get the words out without crying. “I was just telling my relative, if he died in a car accident, I would have at least accepted it because it’s god’s will. At least I would have my grandchildren with me in the house, something from his own blood. But like this, one shot. I cannot accept the reality that he is gone.”

Just days prior, Mesto and his eldest daughter’s bodies were returned to the Tripoli neighborhood of Bab el-Raml, with the entire neighborhood pouring into the streets to mourn their loss. The sound of gunfire echoed throughout the city as residents of Bab el-Raml let out their sadness and their frustration with the tragic deaths.

Mesto’s eldest daughter’s birthday had passed just days prior to their bodies arriving back in Tripoli.

Mesto’s wife, a Syrian Kurd who fled her home country after the start of the decade-long civil war, was still in the hospital in Tartus, her condition constantly fluctuating.

According to Um Moustafa, Mesto’s wife still does not know that her husband and children died.

“I am trying to suppress myself,” she said. “Later on, when his wife comes to the house, what will she do? Find the bed that they used to sleep on? Her children’s clothes? How will she enter the house, call her kids? I have no idea.”

Only 20 people were fortunate enough to survive, with another 100 bodies having been recovered since the boat sank.

No one, besides one of Moustafa’s brothers, knew that he was going to attempt the journey, but all of them agree that the taxi driver was essentially forced to flee to Europe because of the ongoing economic crisis in Lebanon. This was his fifth time attempting to emigrate from Lebanon.

“In this country, if you do not belong to a certain party, you do not live,” Jihad al-Manaa, Mesto’s 43-year-old brother-in-law, told NOW. “Moustafa did not want to live off anyone nor live in these harsh conditions with his family, he sold his car, borrowed money from relatives and other people, and decided to immigrate. This is not the first time he goes by boat, he tried a couple of times before but failed.”

Pushed to the brink

Mesto’s family described him as a “well-behaved” man whose father raised him and his siblings “on the right path.”

The entire family worked together in a taxi business, but it was anything but sufficient when it came to living even just a basic life three years into Lebanon’s ongoing economic crisis.

It was this harsh life that forced Mesto to attempt to leave Lebanon.

He has tried several times before, evening legally going to Ukraine, only to be sent back to his home country.

With the situation in Lebanon only continuing to worsen, with little hope of conditions improving any time soon, Mesto decided once more to attempt to leave Lebanon with his wife and three children.

He did not tell his family, though, as they were against him leaving the country through these methods, except for one of his brothers.

“My son was speaking that he wants to leave,” Um Moustafa recalled. “But I didn’t believe that he will go through it, especially since the last time he went he saw his death with his own eyes. I thought he learned.”

Mesto brought his brother, who is in his 30s, along with him when he went to meet a man only known to him as Abu Firas, the uncle of his friend Talal, and also one of the men in charge of helping smuggle people out of the country by boat in Lebanon, for the first time.

“We arrived there at 3 am and went inside a two-story villa only to find 11 armed men standing in front of us,” his brother told NOW. “It was terrifying, I looked at my brother and asked him ‘What is this place!? What are you bringing me to?’ I left him there but I was afraid if we went inside, they would kill him.”

He did not accompany him to future meetings.

I ran towards him. He did not have any scars. His face was not distorted. He was just sleeping. All of his belongings were with him, his bracelet, watch, as if he’s not even dead.

According to al-Manaa, Mesto paid the thousands of dollars needed to afford to journey for himself and his family with his own money.

Days later, after the first meeting, Mesto was speaking with his brother where he urged him to not go through with the journey and to call Talal to see if he could help him get his money back from the friend’s uncle.

Mesto’s brother said that Mesto had indeed called Talal on the spot, but his friend had refused to go with him to get his money back.

Sensing that his son was considering leaving the country once more, Amer Mesto, 70, warned Moustafa about the dangers of trying to escape Lebanon through smugglers.

“I told him, if you want to do this again do not take your children with you. Do not put them at risk. I will not allow it. Leave them here,” the elder Mesto told NOW. “He kept telling me ‘Father oh father! We are renting the house we live in, there is no electricity, we need to pay 4 million [lira] for [a private] generator [subscription]; this is not a living. I cannot live like this anymore.'”

The day before the family boarded the boat on that fateful journey, Mesto’s children kissed their grandmother goodbye, signaling to her that something was not normal.

Um Moustafa said that one of her granddaughters came up to her and gave her a hug and a kiss, catching Um Moustafa off-guard and causing her to enquire what was going on.

Her granddaughter said that her father was speaking with someone about taking her and her family away from Lebanon and that they had to leave immediately.

Um Moustafa remained silent.

Then, her grandson came and did the same thing, once more causing Um Moustafa to question what was going on.

This time, she received a different answer. The family was just leaving to their aunt’s home.

“I looked at him surprised and said ‘Habibi, even if you’re going, I’m going to see you again no need for all these kisses don’t worry,'” Um Moustafa stated. “Then they left. Their father was waiting for them downstairs. I looked around and found their mother entering their room, grabbed a scarf and went also down. His eldest daughter did not speak to me. She went directly. I rushed to the balcony and found them going into a shady car and left.”

‘The boat of death’

Five days after the boat left shore, Mesto’s brother received a call from Abu Firas saying that Moustafa had arrived safely to Cyprus and that he needed to come by to collect an additional $300 fee for his services. The family did not pay him the extra money.

Unbeknownst to the family, the boat had already sunk and, outside of Abu Firas and the smugglers, no one knew.

A few hours later, Mesto’s sister told the family that the boat her brother was on had sunk off the coast of Tartus.

“We did not believe the news [initially],” Mesto’s brother said. “We did not even think that Moustafa died since he is tall, with wide muscles and also knows how to swim well. He is not any normal person. He’s a man by all means.”

Everyone in the house prayed for Mesto and his family’s safety until, after what felt like an eternity, they received the call that they were all fearing: Mesto was dead.

Amer immediately got into his car and drove to the Lebanese-Syrian border so that he could cross into neighboring Syria and go to the hospital to find his son and his family.

After arriving at the hospital, Amer began searching for his son. He found his daughter-in-law and, after ensuring that she was alive, continued to look for his son.

He was directed to the mortuary and found his eldest granddaughter. The bodies of the other two children remain missing. Whenever there is news of new bodies that were recovered, they go to Syria to see if it is the children.

Amer waited at the hospital for hours as more and more bodies continued to be brought in.

Mesto’s body finally arrived at 2 am.

Amer claimed that he only had to see his son’s leg to know that his beloved son Moustafa had died.

“I yelled this is my son,” Amer stated. “I ran towards him. He did not have any scars. His face was not distorted. He was just sleeping. All of his belongings were with him, his bracelet, watch, as if he’s not even dead.”

Mesto’s brother was asleep when the family got the news that Moustafa had died. When he woke up, he was receiving call after call from everyone in the family, signaling that something urgent was going on. When he finally answered, they told him what happened.

“I stormed to the house, and found everyone crying and screaming,” Mesto’s brother said. “I still could not believe that my brother died. It was a possibility for his family to die but not my brother. He is a swimmer. He’s from Mina (the municipality neighboring Tripoli that sits along the coast) and not from the mountains. When I saw my father, I believed that Moustafa has passed away.”

In the days following the boat sinking, the Lebanese Army arrested a man on the suspicion of helping to smuggle migrants out of Lebanon. According to the Army, he admitted to helping organize the trip.

From what the family was able to piece together, the passengers of the boat were essentially forced to board the ship with the armed smugglers threatening to kill them, despite the passengers saying that the boat, which could at most fit around 60 people, could not fit all 150 of them, and that it was too dangerous to make the journey.

According to al-Manaa, when Moustafa initially refused to board the ship, the boat captain threatened to kill his children.

Mesto’s brother said that when the boat was sinking, Moustafa was able to initially rescue one of his daughters and put her on the side of the boat. Then he went to search for the rest of his family, never to be seen alive again.

Another in a long line of tragedy

The tragedy is one of many migrant ships that have sunk, killing dozens of people who were just doing whatever they could to escape a dire situation.

Earlier this year, another boat carrying close to 90 people sank off the coast of Tripoli after, according to survivors, the military rammed their ship. The military denies these allegations and insists that the smuggler drove the boat erratically in order to evade the authorities, which had caused the boat to sink.

Following the incident, Tripolitans protested for two days, blocking roads and shooting futilely in the air as they expressed their outrage at Lebanon’s politicians for creating the crisis that the country has continued to face.

For three years, Lebanon has been in the midst of one of the worst economic crises that the world has ever seen, with the Lebanese government and parliament failing throughout this time to take any action to combat the crisis.

While the caretaker government has reached a staff-level agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the country’s politicians have been slow to enact any of the required reforms that would unlock billions of dollars from the IMF and, potentially, the international community, something that the IMF has criticized Lebanese politicians for.

Lebanon’s caretaker economy minister, Amin Salam, said that the required reforms will hopefully be passed in October – if there is the “political will” to do so.

It is not just Lebanese seeking to leave the country, with Syrians and Palestinians holding onto the hope that they will be afforded more opportunities and the ability to live normal lives abroad.

Many Syrians feel like they are trapped in Lebanon with nowhere else to go, as most countries are refusing to accept any more refugees.

On top of this, the Lebanese government announced that it was going to start repatriating Syrians back to their home country in coordination with the Syrian government.

According to the plan, the Lebanese government is planning on sending around 15,000 refugees back every month.

Despite many human rights organizations, and even a few governments, arguing that Syria is not safe to return to, the Syrian government insists that anyone who comes back will not be targeted by the government.

However, Syrian survivors of the boat that was carrying Mesto and his family were quickly detained by the Syrian government on the grounds that they were wanted individuals or needed to complete their compulsory military service.

Along with the Syrians that were detained were Palestinians and a Lebanese man, Fouad Hablas, whose brother said that Fouad had been transferred to a military hospital with no explanation.

Palestinians have a similar feeling to that of the Syrian refugees in Lebanon.

Often confined to informal and illegally built refugee camps, the Palestinians face stiff restrictions by the Lebanese government as to what work they are allowed to do and what opportunities are available to them.

Many families have been in Lebanon since they were forced from their homes in 1948 and 1967 by Israel.

If the Lebanese government does not give our rights back, we will take our rights back by ourselves. We do not care about money, it’s the last thing on our minds, we care about our son’s blood and his rights with his children.

With few options and little hope for a future in Lebanon, some view being smuggled to Europe as their only other option.

Former MP for Tripoli Mustapha Allouch is not surprised by the continued attempts to get smuggled out of Lebanon despite the many accounts of people dying as a result.

“People who are venturing in these miserable boats despite the mortal previous experience are running away from a situation which is worse than the possibility of death and are obviously lured by the contraband about the travel situation however what’s happening is a reflection of a depressive state at the national level leading to desperate actions including the high possibility of death,” Allouch told NOW.

He also added that it was hard to combat these smuggling operations because they were essentially “mafias” with all of them having some sort of “official collaborators seeking financial returns.”

According to the Lebanese news outlet Al-Janoubia, those running the smuggling operations in northern Lebanon work with some military and security personnel with the names of all of those involved being “well-known” amongst the population.

In the past, after a boat carrying dozens of migrants sank, there is a small uproar in Lebanon and then there is silence.

This time, the families are looking to hold officials accountable for allowing the deteriorating situation in Lebanon to persist by suing the Lebanese government.

Seeking accountability

When Queen Elizabeth II, the long-reigning monarch of the United Kingdom and its commonwealth, died, Lebanon declared three days of mourning, with all flags being raised at half-staff and Prime Minister-designate Najib Mikati flying to England to attend the funeral.

The over 100 people who died trying to escape Lebanon did not receive anywhere close to the same regard outside of basic statements from politicians and political leaders saying what a tragedy this was and giving their condolences to the families.

A boat sank across the Syrian coast over the weekend, the boat had Syrian and Palestinian nationals on board, but also so many Lebanese. 97 bodies recovered, not ONE day of national mourning in #Lebanon. The Queen of England got 3 days of National mourning in Lebanon.

— Luna Safwan – لونا صفوان (@LunaSafwan) September 26, 2022

It is this lack of recognition and the unwillingness to make any changes that have spurred Mesto’s family to take action against the government.

“Our son’s blood will not fade,” al-Manaa said firmly. “If the Lebanese government does not give our rights back, we will take our rights back by ourselves. We do not care about money, it’s the last thing on our minds, we care about our son’s blood and his rights with his children.”

Al-Manaa cited the emotional turmoil that the family continues to experience as evidence of how little the government cares about them, specifically noting how Amer continues to go to and from Syria to look at the newest bodies recovered from the sea.

“Our government doesn’t care,” al-Manaa stated. “No one even sent their condolences so we decided as a group and the lawyers to move with this project till the end. Our children are good people.”

The family says that they want to hold the government accountable, but that they will not block roads or do anything to disturb everyday life in the country, instead preferring to take the legal route because they “still believe that there’s a law and good lawyers that can defend the rights of these people.”

Ahmad al-Karma, one of the lawyers for the families, told NOW that a group of lawyers had volunteered to take on the families’ case after hearing news about the boat so that the truth behind why the boat sank and the criminals behind the smugglings can be brought to light. More importantly, it could hopefully provide the families some semblance of justice.

However, while Mesto’s family may still believe that Lebanon is ruled by law, al-Karma is much more skeptical that the government would play fair should the case be brought to Lebanon’s judiciary.

“Unfortunately, the system is broken,” al-Karma stated. “There are a lot of loopholes in the justice system, for example, the judge who should follow the law is corrupt. Therefore, we ask to have an international legal team to look into this case to seek Justice for these people. This is not the first or last boat that had the same case.”

Al-Karma argued that unless things change in Lebanon and the government finally takes concrete action to end the ongoing crisis, then there will undoubtedly be further smuggling attempts and just as many more that end in death.

“The people are desperate, they even pay beforehand not knowing if they will die or make it,” the lawyer exclaimed. “The government suspended new passports, making people want to travel illegally. They are suppressing the people not letting them work, live, travel. They spend millions of dollars on other things, and when it comes to the Lebanese citizen, they neglect his/her basic right to have a passport. There is no choice for the Lebanese citizens. It’s either the boat or death.”

In the coming days, multiple families who lost loved ones when the boat sank will meet to discuss their plans on how best to move forward with their case.

Al-Manaa says that they will go to every court in Lebanon to seek justice if they have to.

The family desperately hopes that the situation in Lebanon will improve soon, especially after their tragic loss.

Amer has been forced to sell much of their property because the family is in debt and needs to be able to afford to pay their bills.

“They see other people being accepted and making it through in Europe, so they immediately get excited, sell everything, take money from close people and hop on the nearest boat in hopes of a better life,” he stated, urging countries not to accept migrants who enter their countries illegally, as it gives others hope that they will meet the same fate.

The grieving mother opened her phone to a picture of Mesto in his coffin and kissed the screen, tears already streaming down her face.

“This country has nothing,” Um Moustafa said. “My son worked and got paid a million Lebanese lira and spends it on the motor. He used to tell me ‘I am dead in this country, I am unable to do anything to help my family! They want me to steal, I will not steal. It’s true that we are gathered together, but I just feel useless in this country.'”

Nicholas Frakes is a multimedia journalist with @NOW_leb. He tweets @nicfrakesjourno.

Rayanne Tawil contributed to this report.