New Year’s Eves are to look back and draw lines, count achievements and plan for the next year. So here we go.

It wasn’t easy to get NOW back online in 2021. I also never expected that I would be here for its rebirth from the ashes of the August 4 explosion.

I came back to Lebanon after the blast. It is moments like this when one realizes how little time they have left with loved ones. You have to be there to spend it with them.

“You’re crazy, eh?” our publisher Eli Khoury greeted me when I returned.

Me telling this story is probably long overdue. Looking back at 2021, I realize I didn’t write much. I mostly edited and annoyed my new coworkers with deadlines and comments left on the margins of their drafts.

But the story of NOW is the first I need to tell. I started my reporter job at NOW in August 2009. It was right after a shooting in Aicha Bakkar between Amal gunmen and Future Movement supporters had claimed the life of a woman who was on the balcony trying to warn her husband to take shelter.

Hanin Ghaddar, the managing editor of NOW at the time, assigned me that story. I went to Aicha Bakar and spoke to people. I had been hired to replace Maysam Ali, who was leaving to do her Master’s in the US, and I inherited an apartment next to AUST from another NOW writer, Ben Ryan, when he left Lebanon.

NOW became my second home for six and a half years, and my coworkers were my second family. It’s hard to come into the office and look at this newsroom without Hanin – who is now in Washington, writing a book on Lebanon – and the Michaels. Michael Young, now editor at Carnegie Middle East Institute, and Michael Karam, who is now in the UK and has written books and produced a documentary on Lebanon’s wine industry. I owe to all three of them the fact that I am here today.

They made NOW a melting pot, a place where reporters of mixed backgrounds sat together and brainstormed and put together quite amazing pieces of journalism. They taught us we needed to be on the field.

It’s hard to be in the NOW newsroom without Sunny Ajami, without Matt Nash and Nadine Elali, Hayeon Lee, Shane Farrell, Nick Lowry, Alex Rowell, Aline Sara, Dana Moukhallati, Amani Hamad, Albin Szakola, Myra Abdallah, Yara Chehayed, Loran Peterson, Raphael Thelen, Luna Safwan, Ranya Radwan, Angie Nassar and Justin Salhani, Naziha Baassiri.

We made a great team. Happy hour with them in Gemmayzeh was amazing, holidays spent in the newsroom were something we’d enjoy and our end-of-the-year parties were to be remembered. Oh, the potluck parties at Aline Sara’s grandma’s place!

They are now all scattered across the world. I drifted away for a few years while I covered the Balkans. The Coronavirus had us on numerous lockdowns, Lebanon’s financial crash has destroyed hopes and dreams, and the August 4 explosion has ravaged Beirut.

Ten years of reports, dispatches, features and opinion pieces are now gone and it will probably take years to rebuild what we’ve lost.

It is 2021 (still) and Lebanon is now running on fumes, gasping for oxygen.

But there is still some life here. A few of us still dwell in Beirut. We’re not giving up, mostly out of the conviction that Lebanon’s story needs to be told from within Lebanon.

It has been almost 6 months since we’ve been online again and it has been worth every minute of the hard work it required.

We published 260 stories and a huge thank you goes to all the people who picked up the phone, replied to our messages when we asked for interviews, read our pieces and gave us feedback.

Here are some of what we think are our best. May we have a better 2022. From our core team – Ronnie Chatah, Dana Hourany, Sally Abou al Joud, Nic Frakes, and yours truly, Ana Maria Luca – and from our contributors – Fred Bteich, Makram Rabah, Luna Safwan, Mariam Kesserwan – a big thank you for reading us.

The Anarchist and the Dinosaur

Ronnie Chatah’s first piece for NOW was published the day we launched and it expressed probably better than anything else our raison d’etre as a media outlet.

We came up with the idea during our second meeting in person after the pandemic, while sipping coffee in a garden in Mar Mikhael and planning editorial content. We saw that a generation of Lebanese, 35-40, was caught in the middle of the political turmoil after 2019. They had been there in 2005 when they protested against the Syrian occupation, in 2015 when they rose against corruption, and in 2019 during the Thawra.

“The Anarchist and The Dinosaur are hostages to the same machine. One goes extinct while the other barely breathes. And any future revolt will be destroyed by the same formidable force that turned deliberation to death,” Ronnie wrote.

Our age of innocence

Luna Safwan took a trip down memory lane as she sat down, looked at her teenage diary and realized the scars political instability, war, and strife leave on people. She wrote this heartfelt story about why she shares sunsets on Instagram when protesters across the country burn tires. In fact, it is about why young Lebanese leave their country.

“In Lebanon, there’s an entire generation that grew up longing to leave, to emigrate, to start somewhere else. There is a line we often read on the walls of some Arab countries – including Lebanon – which says: “Your country is not a hotel, you do not check out when things get rough.” It no longer makes sense in a country where farewell parties overshadow weddings, in the summer of 2021.”

Lokman’s wise mother

On the morning of February 4, 2021, Luna Safwan’s call woke me up. “Lokman is missing,” she told me. “He was in the South.”

Lokman Slim’s death was shocking. There was no doubt that he had been receiving threats for years already, that his political discourse was not comfortable to many in Lebanon, especially Hezbollah. No real investigation into his death has been conducted.

Lokman Slim left behind a lifetime of work challenging the official discourse on the memory of the civil war, trying to expose the truth of the facts buried in recycled oral history. His vision remains, his legacy of ideas stronger than ever.

On the day marking ten months since publicist Lokman Slim’s murder, historian Makram Rabah paid homage to Salma Mershak, Lokman’s mother and his first mentor.

Between the scents of tear gas and orange groves

Tripoli residents took to the streets in January 2021 in opposition to the renewed nationwide COVID-19 lockdown and the absence of corresponding social protections.

Gathered outside the Ghandour building, a planned five-star hotel that was never completed, citizens of all ages spoke to Matt Kynaston and Rachel Bessette of hunger, frustration, and anger.

Matt and Rachel looked beyond the cliches of the ‘poorest city on the Mediterranean’ and the hyperbolized ‘Kandahar of the Middle East’.

Poking the hornet’s nest

Investigative judge Tarek Bitar took over the Beirut blast investigation in February 2021, after his predecessor Fadi Sawan was sacked by the Supreme Court which ruled in favor of two former ministers who claimed the magistrate was not objective.

There are currently 18 lawsuits against Tarek Bitar and his investigation was frozen four times in order to protect a few former ministers and dignitaries from being questioned as suspects in the probe.

Real investigations into crimes committed in Lebanon are rare. Dana Hourany tried to look into what magistrates like Tarek Bitar and investigators in general risk for trying to dig deeper into crimes committed in Lebanon.

Collapse begets violence

Gunfights, tribal vendettas, bank robberies and increased criminality is what follows when degrading state institutions are unable or no longer possess the legitimacy to ensure law enforcement in a failed state. In 2021, Lebanon has gradually seen Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan enacted in reverse on its streets.

The Lebanese social media bubble has watched in awe a man showing up with a “bouquet” of snakes at a gas station so he could cut the line and fill his gas tank amid a fuel crisis. Gunfights over fuel happened at least weekly during the summer.

Sally Abou al Joud spoke to experts to explain why violence was not just a matter of security, but a matter of lack of public trust.

How Lebanon fails child sex abuse victims

No one protects children from sexual predators in Lebanon. From lack of awareness among parents and the social pressure of shame, to legal obstacles like the 10-year statute of limitations and corruption in the judiciary system, a multitude of factors lead to the lack of prosecution of child abuse.

Nicholas Frakes took a detailed and well researched look at how sexual abuse against children is not prosecuted in Lebanon, despite the perpetrator being sentenced abroad, starting from the case of Maronite celebrity priest Mansour Labaki. Victims are many times silenced, especially in cases involving clergy, and cases are politicized. Spiritual punishment is accepted instead of legal punishment.

Matt Kynaston spoke to fashion icon Samer Khouzami, who courageously told his story of abuse on social media at the beginning of 2021 to encourage other victims to speak up.

The day they slaughtered Beirut

On the one-year anniversary of the August 4 Beirut port explosion, neurosurgeon Fred Bteich wrote this obituary for his hometown. It’s a heartbreaking elegy of the Lebanese expat, who feels the pain of losing friends, the guilt of being away and not being able to mourn, the anger at impunity.

Who could forget about the day their mother died? he asked.

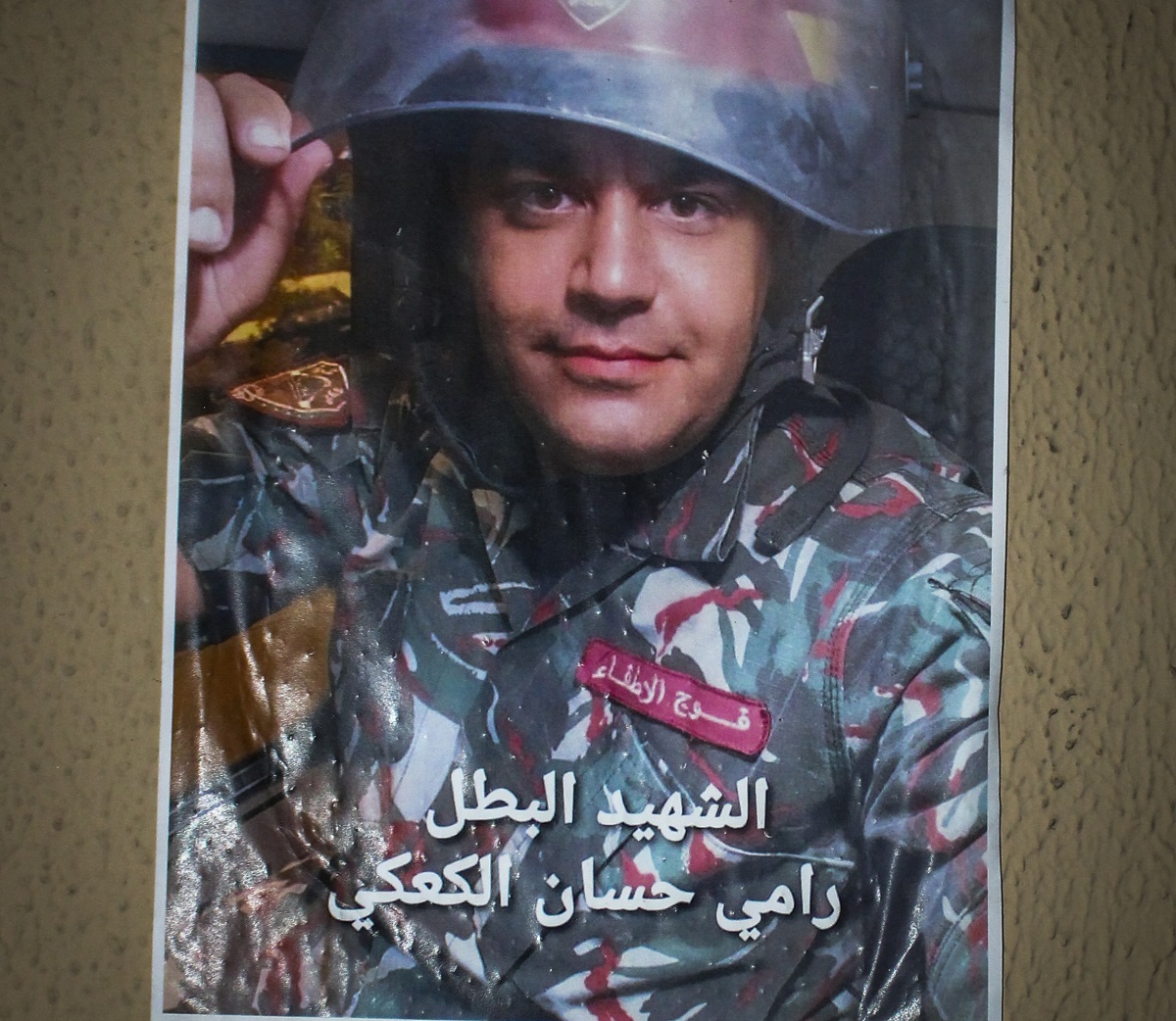

His last gift

The victims of the Beirut port blast are most of the time mentioned as a number – over 200 or 227.

On the anniversary of the blast, Sally Abou al Joud profiled Rami Kaaki, a 35-year-old firefighter who was dispatched to death on August 4, 2020 together with his coworkers.

It’s also a story of how one woman lost her partner, dealt with the pain, but had to brace up and live again in order to raise two children. It will probably bring tears to your eyes.

The struggle to stay

When most of your friends choose to leave the country, the struggle to stay goes beyond the material. Dana Hourany wrote this piece in the midst of the fuel crisis, when electricity was scarce and many towns in Lebanon were left without electricity for days in a row.

The dark road to judicial independence

The mysterious death of October 17 activist Faysal Sfeir, deemed a suicide by investigators who wrapped up the probe in a few hours, raises questions over other deaths and also points to the lack of independence of the judiciary, well beyond the Beirut blast probe. Several deaths that occurred after 2019 away from the spotlight have not been properly investigated and that is worrying, Mariam Kesserwan wrote. A reminder that impunity is an everyday occurrence in Lebanon and no one has access to a fair investigation.

Ana Maria Luca is the managing editor of @NOW_leb. She tweets @AnaMariaLuca79.

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOW.